Credit Risk Management

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Describe key elements of... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

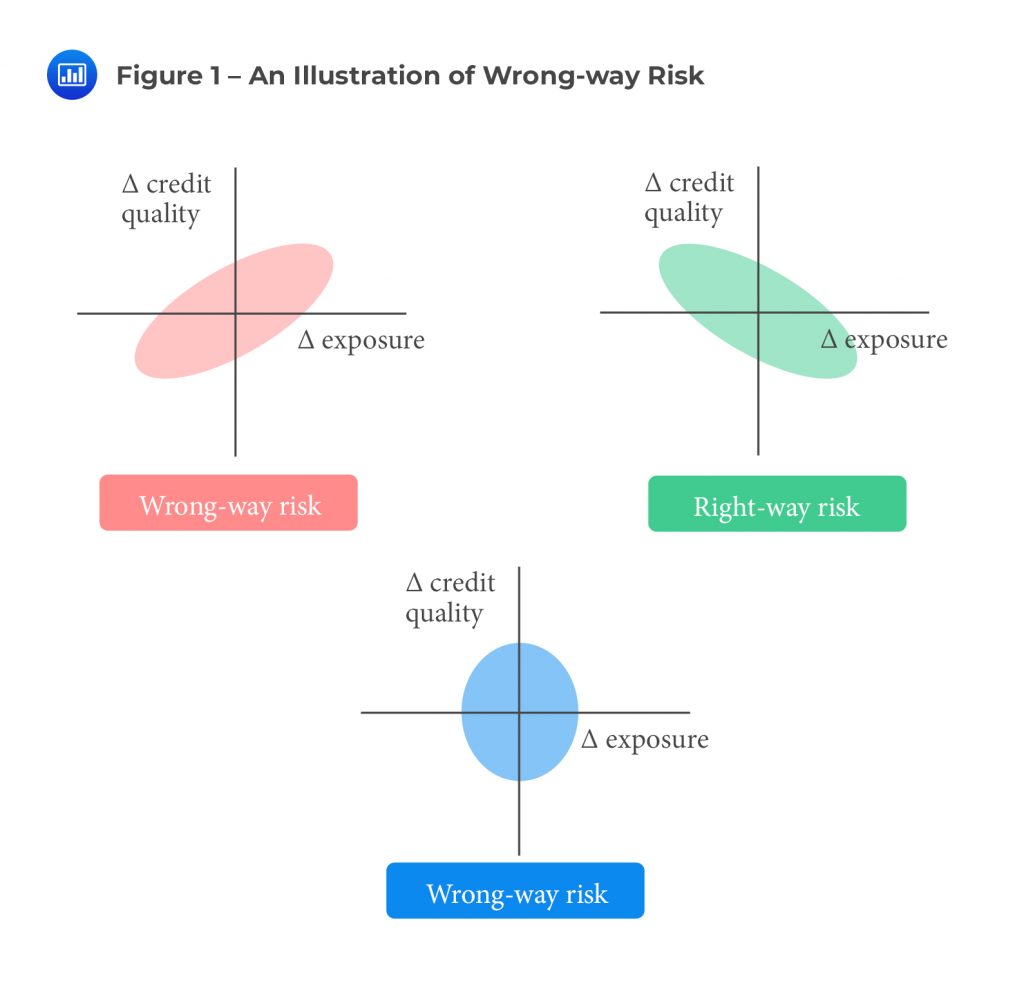

One of the key issues that arises when analyzing CCR is wrong-way risk. It is defined as the risk that occurs when exposure to a counterparty is adversely correlated with the credit quality of that counterparty. In short, it is the risk that default risk and credit exposure will show an unfavorable dependence and tend to increase together. It is important to note that wrong-way risk does not apply to fixed-rate loans.

Wrong-way risk results in an increase in counterparty credit risk and, therefore, increases CVA. At the same time, it leads to a reduction in DVA. Right-way risk, on the other hand, exists when there’s a favorable dependence between exposure and credit quality. In this case, the linkage between exposure and the counterparty’s probability of default produces an overall decrease in counterparty risk. The implication of this is that CVA decreases, but at the same time, DVA increases.

Both wrong-way and right-way risks are frequently observed in practice. For instance, consider the case of a middle-level bank that holds a large unhedged portfolio of derivatives with a dealer. If market variables move in such a way that the value of the derivatives to the bank is negative, the bank will be losing money. If losses accumulate for the bank, it is likely that the bank will be unable to make the required payments and, consequently, default. While that happens, the value of the portfolio to the dealer will be positive, and therefore, the dealer’s exposure will be increasing. This results in a wrong-way risk for the dealer. The probability that the bank will default when it has a large negative exposure is large.

From a historical perspective, wrong-way risk has commanded more attention than right-way risk, but both types of risk are hugely important. It is, indeed, imperative that institutions strive to increase right-way risk while decreasing wrong-way risk.

Examples of Wrong-way Risk

Examples of Wrong-way RiskIf a trader buys a put option on a stock whose performance has a strong positive correlation with the performance of the counterparty, there’s an obvious case of wrong-way risk.

Consider a situation where Smart Tech buys a three-month put option from Cortana Inc., with Alpha stock as the underlying. At expiry, Alpha stock has a price of $45, and the put is, therefore, ITM with a value of $5 (ignoring the premium). During the same period, Cortana’s stock plummeted after a landmark lawsuit loss against another firm. In this case, the credit exposure of Smart Tech to Cortana Inc. has increased, but this has coincided with a deterioration in Cortana’s creditworthiness

This situation can also be brought about by macroeconomic factors such as interest rates and inflation, which could cause a fall in the underlying asset (Alpha stock) aside from exciting the financial instability of the counterparty (Cortana).

Consider a case where a commercial bank in a developing market such as Venezuela enters a cross-currency swap with a U.S. bank (developed market). Under the terms of the deal, the commercial bank (the counterparty) will deliver developed market currency (USD) in return for local currency. If macro-economic conditions take a turn for the worse and the value of the local currency declines (depreciates), the value of the transaction to the U.S. bank substantially increases; exposure increases significantly. The counterparty will be required to spend more of the local currency to deliver U.S. dollars as agreed; the risk of default, therefore, increases.

An increase in exposure for the U.S. bank, coupled with an increase in the counterparty’s risk of default, amounts to wrong-way risk. But if the U. S. bank’s exposure increases but the counterparty’s probability of default declines, there will be a reduction in counterparty risk. That would effectively be a case of right-way risk.

Consider a case where Metropolitan Bank, based in the Philippines, enters a total return swap (TRS) with Alpha Inc. As per the swap agreement, Metropolitan pays the total return on its bond (BND_MTN_AA ) and receives a floating rate of LIBOR plus 5% from Alpha Inc. If interest rates start rising globally, the credit position of Alpha Inc. will start deteriorating, and this will coincide with an increase in its payment liabilities to Metropolitan.

Consider a different case where Metropolitan Bank enters a credit default swap with Alpha Inc. as the protection seller. The reference asset is a $50m bond investment in Bank ABC. Therefore, Alpha Inc. provides credit protection to Metropolitan in the event Bank ABC defaults on its obligations. If macroeconomic conditions take a turn for the worse, there’s a real chance that Bank ABC will default, and at the same time, the protection seller (Alpha Inc.) will be unable to fulfill its obligations.

A commodity entered with a consumer who seeks to hedge the price of a good can yield wrong-way risk.

Consider the case of an airline wary of an increase in the oil market. The airline decides to use derivatives to hedge all of its consumption by entering forward contracts. As per the contracts, the dealer agrees to sell oil in the future at $30 per barrel. As maturity approaches, the price rises to $50 per barrel. This is a win for the airline because they will now be buying cheap. But that also means there’s a big loss for the dealer. The problem gets worse if the dealer has concentrated (many) short positions because there will be a flood of claims tabled by various parties (possibly other airlines). This will put intense pressure on the credit quality of the dealer.

In this case, the positive value (exposure) from the perspective of the airline coincides with an increase in the dealer’s probability of default. This increases overall counterparty risk and produces wrong-way risk.

Commodity forwards may also yield right-way risk when entered with a producer who seeks to hedge the price of their goods.

Consider the case of an oil producer wary of a decline in the oil market. The producer decides to use derivatives to hedge 50% of its production by entering forward contracts. According to the contracts, the dealer agrees to buy oil in the future at $50 per barrel. As maturity approaches, the price declines to $30 per barrel. In this case, the producer (the counterparty) is likely to default and they are losing money on the unhedged part of their production. But with the price of oil so low, the value of the forward contracts to the dealer is also low. In this case, the derivatives have a positive value (exposure) to the oil producer and a negative value to the derivatives dealer.

As such, the dealer’s exposure is likely to be low when the oil producer (counterparty) defaults.

Consider a situation where Smart Tech buys a three-month call option from Cortana Inc., with Alpha stock as the underlying:

The call is therefore ITM with a value of $5 (ignoring the premium). During the same 90-day period, Cortana’s stock rallied under strong economic conditions. In this case, the credit exposure of Smart Tech to Cortana Inc. has increased, but this has coincided with an improvement in Cortana’s creditworthiness.

Specific wrong-way risk (SWWR), arises due to the specific characteristics of the counterparty or the transaction, which include things such as a rating downgrade, poor earnings, or litigation.

General wrong-way risk (GWWR), on the other hand, is driven by macro-economic relationships, which include things such as interest rates, pandemics, political unrest, or inflation in a particular region.

The two types of risk differ as follows:

$$ \textbf{Figure 2 – General WWR vs. Specific WWR} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c|c} {\textbf{GWWR}} & \textbf{SWWR} \\ \hline \text{Should be priced and managed correctly} & {\text{Should, in general, be avoided, as it may} \\ \text{be extreme}} \\ \hline {\text{Relationships may be detectable using} \\ \text{historical data}} & {\text{Hard to detect except by a knowledge of} \\ \text{the relevant market, counterparty and the} \\ \text{economic rationale behind transaction}} \\ \hline {\text{Can potentially be incorporated into} \\ \text{pricing models}} & {\text{Difficult to model; should be addressed} \\ \text{qualitatively via methods such as} \\ \text{stress-testing}} \\ \end{array} $$

To quantify WWR, a risk manager has to model the relationship between credit, collateral, funding, and exposure.

The modeling process is complex due to a number of issues:

Collateral is a good way to reduce exposure. WWR can cause exposure to increase significantly and, therefore, it is important to consider the impact of collateral on WWR.

When exposure is increasing gradually, collateral does a good job to minimize the impact of wrong-way risk. This is the case because derivative agreements have clauses that require parties to post collateral after a certain threshold is exceeded. This extra collateral is, therefore, easy to request and receive.

But in cases where there’s a sudden jump in exposure, collateral does very little in the way of mitigating WWR. For example, if there happens to be a 20% currency devaluation that coincides with sovereign default, collateral is rendered almost useless because it may not be received at all.

CCPs may, particularly, be prone to WWR because they rely so much on collateral as protection. CCPs tend to closely manage and monitor membership by only admitting parties with certain credit quality.

Moreover, all members have to provide an initial margin and also make contributions to the default fund that serves as an extra layer of cushion. But there’s a problem: These initial margins and default fund contributions are based on the market risk of a portfolio. As such, this separation of credit risk and market risk may culminate in a situation where collateral requirements ignore WWR!

For CDS, in particular, CCPs are faced with an uphill task trying to quantify the WWR component when setting initial margins and default fund contributions. That’s because higher credit quality can increase WWR (when things take a turn for the worse, previously highly rated credits can get hit quite hard).

The collateral posted carries WWR; members may post highly risky or illiquid securities.

Practice Question

Which of the following statements regarding general wrong-way risk (WWR) is correct?

A.General WWR is based on structural relationships that are often not captured via the real world.

B.General WWR is difficult to model and risky to use given the naïve correlation assumptions.

C.General WWR is based on macroeconomic behaviors.

D.All of the above.

The correct answer is C.

Option C is correct because general WWR is based on macroeconomic behaviors.

Option A is incorrect. Specific WWR is based on structural relationships that are not often captured via the real world.

Option B is incorrect. Specific WWR is difficult to model and is risky to use given the naïve correlation assumptions.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.