Estimating Default Probabilities

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Compare agencies’ ratings to... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

In simple terms, collateral refers to an asset supporting risk in a legally enforceable way. Why is collateral necessary? At any point during the life of a derivative contract, one party will have a positive exposure (the party will be “winning”) while the other will have a negative exposure (the party will be “losing”). The winning party needs a sign that the counterparty is committed to delivering/making available the winnings in accordance with contractual stipulations. The party with the negative exposure will, therefore, post collateral in the form of cash or marketable securities to the party with positive exposure.

In most cases, collateral is bilateral, i.e., either side of a transaction is required to provide collateral to the other side with positive exposure. The collateral receiver becomes the permanent economic owner of the collateral only upon default by the collateral giver. If the collateral giver defaults, the non-defaulting party has a legally enforced right to seize the collateral and use it to offset any losses relating to the MTM of their portfolio.

However, collateral may also be one-way, particularly when trading with institutions that have an impeccable credit history.

Counterparties regularly mark their positions to market and calculate the net value. After that, the party that has a negative exposure may be required to post collateral against their position in line with the dictates of the contract. In most cases, collateral posting takes place in blocks at specified points during the life of the contract.

There are several motivations for managing collateral:

Since collateral agreements are often bilateral, collateral must be returned or posted to the other party as soon as exposure decreases. Posting and returning collateral are not materially different. However, the party returning collateral may be asked to deliver specific instruments.

The Credit support annex, CSA, is a document that sets out the terms for the provision of collateral in a derivatives contract. It forms part of the ISDA Master Agreement which is the umbrella document that sets out the overarching terms between parties in a contract. The CSA need not be part of the Master Agreement but in recent years, it has become an important part of bilateral OTC agreements.

As with netting, ISDA has a major input in the wording and enforceability of the CSA throughout a large number of jurisdictions. The CSA covers the same range of transactions at the Master Agreement but collateral requirements are still based on the net MTM of all the transactions. However, the CSA will often give parties room for negotiations with regard to a number of parameters and terms that dictate posting/return of collateral. Precisely, parties are allowed to deliberate over the following issues:

The CSA defines the following parameters:

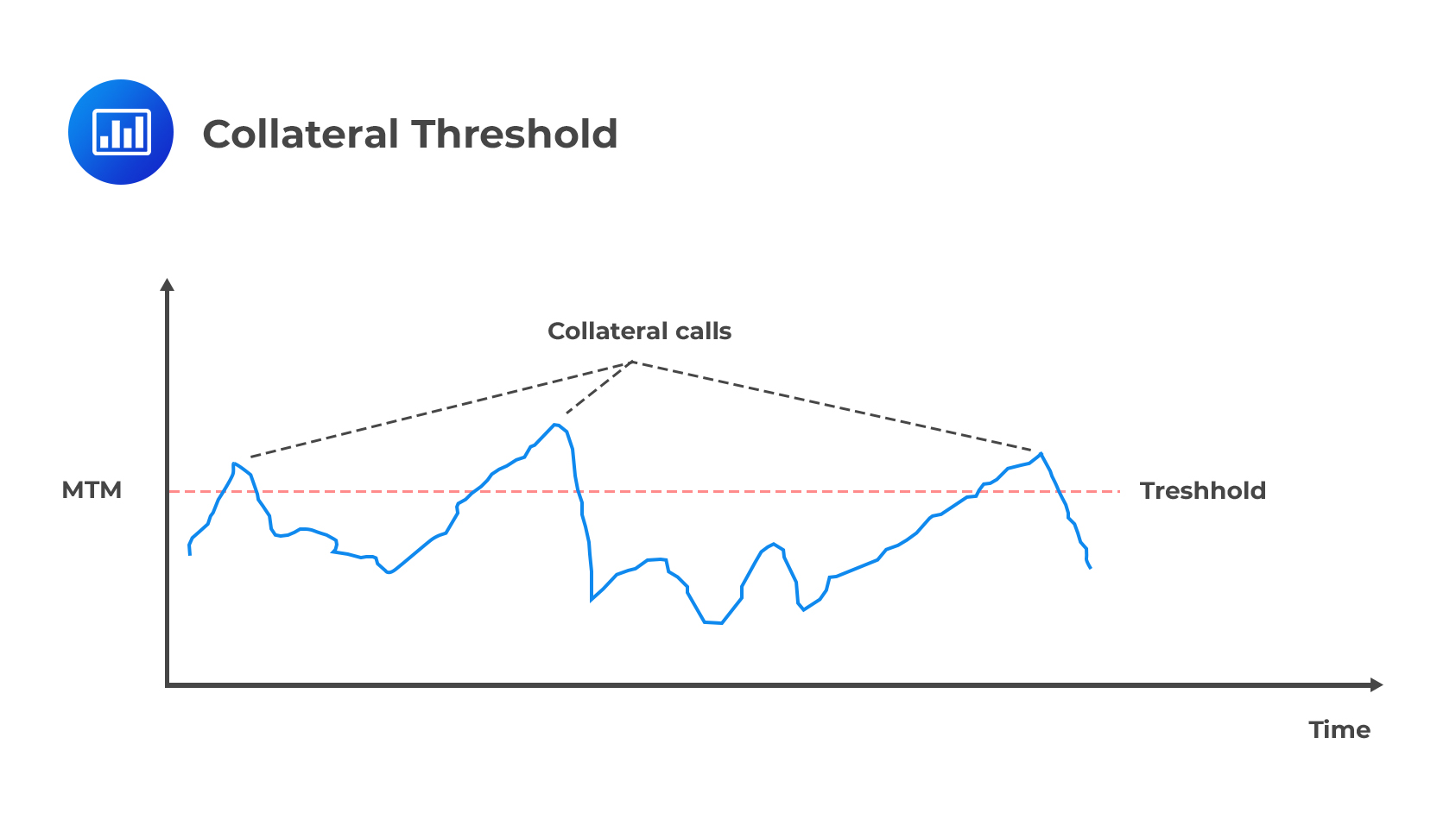

The threshold is the amount below which collateral is not required. If the MTM is below the threshold then no collateral can be called and the underlying portfolio is, therefore, uncollateralized. But as soon as the MTM rises above the threshold, the incremental amount of collateral has to be called for. For example, let’s assume that a contract specifies a threshold of $10,000 but the MTM, following today’s market movement, stands at $12,000. In this case, $2,000 worth of collateral would be required.

A non-zero threshold indicates that counterparties are willing to tolerate counterparty risk up to a certain level. In some cases, the threshold is set at zero, indicating that collateral needs to be posted under any circumstance.

A non-zero threshold indicates that counterparties are willing to tolerate counterparty risk up to a certain level. In some cases, the threshold is set at zero, indicating that collateral needs to be posted under any circumstance.

Also known as independent margin in bilateral markets, the initial margin refers to the extra collateral required independent of the level of exposure. Every party must post the initial margin irrespective of the MTM of the underlying portfolio, and this usually happens upfront. In effect, the initial margin serves as an extra layer of protection against potential risks such as delays in receiving or returning collateral and costs in the close-out process.

The initial margin and the threshold work in opposite directions. “How exactly?” you might ask. Remember that, by definition, a threshold is the amount below which collateral is not required, and in essence, therefore, it limits or rather puts a cap on the amount of collateral. The initial margin, on the other hand, specifies an amount of extra collateral that must be posted irrespective of the MTM of the underlying portfolio. In essence, therefore, the initial margin actually increases collateral and leads to overcollateralization, while the threshold leads to undercollateralisation.

This is the minimum amount of collateral that can be called at a given time. Counterparties often set a minimum in a bid to avoid the workload associated with the frequent transfer of insignificant amounts of collateral. The minimum transfer amount and threshold are additive in that the MTM must exceed the sum of the two before any collateral can be called.

When posting or returning collateral, the quoted amount is usually rounded to a multiple of a certain size to avoid dealing with awkward quantities that may not be deliverable. Some securities, e.g. cash, that can be used as collateral may not be infinitely divisible. The rounding may always be up or down, or, it might always be in favor of one counterparty. For example, collateral may be rounded up for all calls and rounded down for all returns.

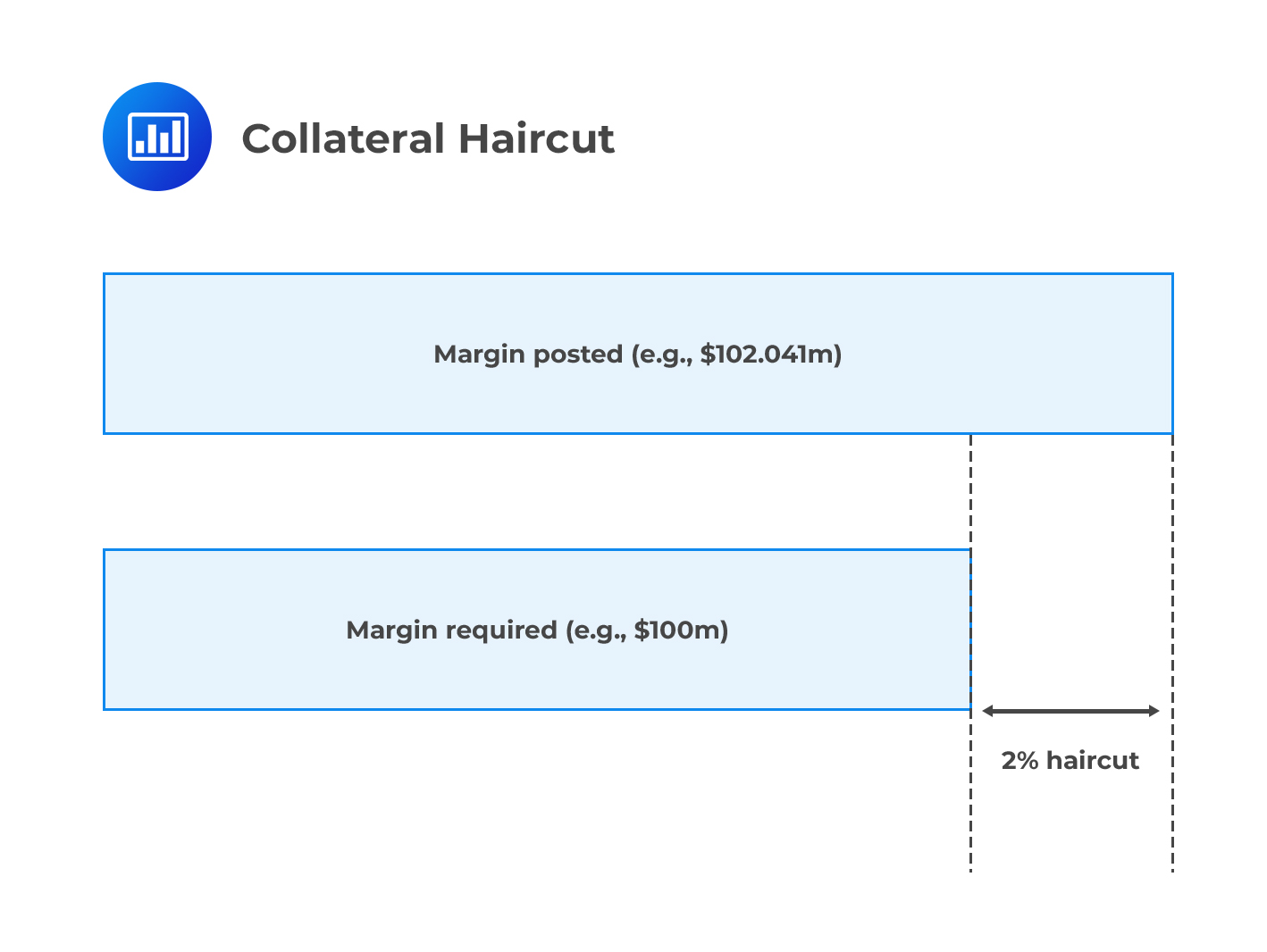

In most cases, it is difficult to liquidate collateral at its market value, possibly in stressed market conditions. Therefore, a repo margin (called haircut in the US) is imposed. It is the difference between the market value of the security used as collateral and the value of the exposure.

A haircut of 2%, for example, means that for every unit of that security posted as collateral, only 98% of the credit (“valuation percentage”) will be given. To see how this works, assume that a 2% hair cut applies, and the collateral call amounts to $100 million. In this case, collateral with a market value of $102.041 million \(\left[=\frac {$100m}{1-0.02} \right]\) would have to be posted.

In essence, the haircut protects the buyer or lender against:

In essence, the haircut protects the buyer or lender against:

Most of the assets used as collateral are subject to haircuts except cash posted in a major currency.

Credit quality refers to the creditworthiness of a counterparty as indicated by their credit rating (issued by a reputable, widely recognized rating agency). As the credit quality decreases (increases), the need for collateral increases (decreases). In fact, thresholds, initial margin, and minimum transfer amounts may all be linked to credit quality. A party rated AAA, for example, may not be requested to post an initial margin, and it may as well enjoy higher threshold and minimum transfer values. The table below illustrates this:

$$ \textbf{Example of rating-linked collateral parameters} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c|c|c|c} \textbf{Rating} & {\textbf{Initial Margin} \\ \textbf{(% of total notional)}} & \textbf{Threshold} & \textbf{Minimum Transfer Amount} \\ \hline \text{AAA/AAa} & {0} & {$250\text{m}} & {$5\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{AA+/Aa1} & {0} & {$150\text{m}} & {$2\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{AA/Aa2} & {0} & {$100\text{m}} & {$2\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{AA-/Aa3} & {0} & {$50\text{m}} & {$2\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{A+/A1} & {0} & {0} & {$1\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{A/A2} & {1\%} & {0} & {$1\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{A-/A3} & {1\%} & {0} & {$1\text{m}} \\ \hline \text{BBB+/Baa1} & {2\%} & {0} & {$1\text{m}} \\ \end{array} $$

Although collateral parameters are mostly linked to credit ratings, they can also be linked to a counterparty’s market value of equity, traded credit spread, or even their net asset value.

The “credit support amount” is the amount of collateral that one counterparty must have transferred to the other party at a given point in time. As mentioned previously, collateral requirements are set in a way that minimizes operational costs. The collateral that may be requested at a given point in time is subject to the threshold and minimum transfer amount as discussed above.

In the collateral management process, the calculation of the credit support amount is influenced by the contractual parameter of MTAs. MTAs contribute to a path-dependent series of margin requirements, where the margin call at a specific point in time is affected by the balance at a preceding time. This connection underscores the importance of sequential dependency in margin calls within financial contracts.

Suppose two counterparties enter into a derivative contract which includes an initial margin requirement of $10,000 and a threshold of $5,000. On a particular valuation day, the mark-to-market value of the derivative in favor of Counterparty A is $18,000. What is the credit support amount that Counterparty B needs to post?

Solution:

The credit support amount refers to the variation margin that must be posted when the mark-to-market exposure exceeds the threshold. Initial margin is posted separately as an independent amount and does not reduce or replace the variation margin requirement.

Given:

First, calculate the exposure above the threshold:

\[ \text{Exposure above threshold} = \$18,000 – \$5,000 = \$13,000 \]

Since variation margin is calculated independently of initial margin, Counterparty B must post the full amount above the threshold:

\[ \textbf{Credit Support Amount} = \$13,000 \]

Hence, Counterparty B must post $13,000 in variation margin.

Consider two counterparties with an existing collateral agreement and the following measures in place: a threshold of $4,000, a minimum transfer amount (MTA) of $1,000, and no initial margin. The current collateral balance stands at $3,000 in favor of Counterparty A. On the following valuation day, the mark-to-market value moves to $6,500 in favor of Counterparty A. How much collateral must Counterparty B post or receive after this market movement?

Therefore, the collateral balance remains unchanged due to the MTA provision, and no additional collateral is required to be posted by either counterparty.

The valuation agent is the party charged with calculating the credit support amount in line with the dictates of the credit support annex.

In trades where there’s a big gap in the credit quality between the counterparties, the party with better credit quality (which we may call the senior party) often insists on being the valuation agent for all purposes. The party will evaluate the trade status at the end of each day of trading to determine whether collateral needs to be called or returned. The smaller (less creditworthy) party is not obligated to post or return collateral unless it receives a notification from the valuation agent, but the latter may be under obligation to make collateral returns where possible. In trades where both counterparties have largely the same credit quality, they may both act as valuation agents.

In general, the valuation agent calculates:

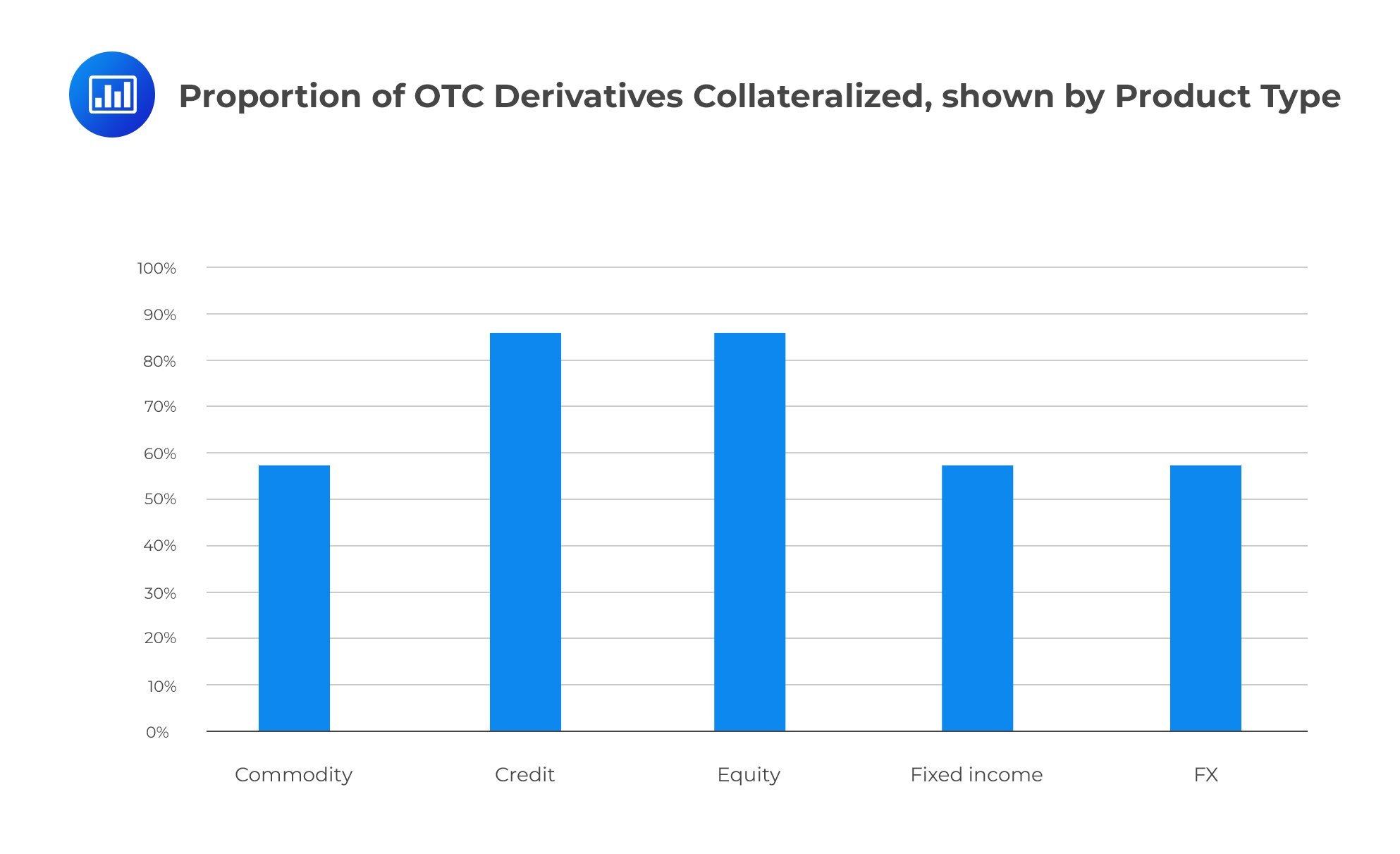

Since the 2007/2008 financial crisis, collateral requirements have been tightened in OTC markets around the world. As the figure below shows, credit derivatives are the most collateralized due to the high volatility of credit spreads, while the commodities market is the least collateralized.

There are certain key aspects that every collateral agreement must set out:

There are certain key aspects that every collateral agreement must set out:

There are many eligible securities that can be posted as collateral. The most common assets include the following:

Most parties prefer cash over any other eligible collateral in part because it is liquid and can be delivered at short notice without too much operational risk. The availability of cash, however, tends to be limited in times of market stress. Noncash collateral comes with several problems, particularly in terms of Rehypothecation and price volatility.

For centrally cleared transactions, collateral disputes are rare and are quickly solved because the central counterparty is the valuation agent. Central counterparties are able to do this because their valuation methodologies are market standard, transparent, and robust. For OTC derivatives, however, disputes are fairly common.

In most cases, a dispute over a collateral call in OTC markets arises due to one or more of the following:

Most disputes have much to do with the non-transparent and decentralized nature of the OTC market. Collateral agreements usually specify valuation differences that are considered tolerable. If a dispute is based on a valuation difference within the tolerable level, counterparties are allowed to “split the difference.” If not, the cause of the discrepancy has to be investigated further. Disputes lead to a situation where one party has a partially uncollateralized exposure which lasts until a solution is found.

Whenever there is a dispute, counterparties employ the following resolution steps:

The disputing party is required to notify the counterparty of its intention to dispute the exposure or collateral calculation. This should happen no later than the close of business on the day following the collateral call.

The disputing party transfers the undisputed amount and the two parties immediately launch a dispute resolution mechanism in an attempt to unearth the source of the dispute within a certain timeframe.

If no solution is found within the specified timeframe, the counterparties request MTM quotes from several market makers (usually four).

A good way to minimize the possibility (and frequency) of disputes and valuation differences is to perform reconciliation at regular intervals. Reconciliation can be done before the start of trading or during trading to pre-empt future disputes.

In the OTC market, three possible collateral agreements exist:

In some cases, a counterparty may want their collateral returned at some point after posting. Which begs the question, just why would a party want their securities returned? There are two main reasons:

In these circumstances, the collateral giver makes a substitution request to replace the collateral in use with some other eligible collateral of equivalent value. In some trades, substitution can only happen with consent from the collateral receiver/holder. If no consent is required, then the holder cannot turn down the request.

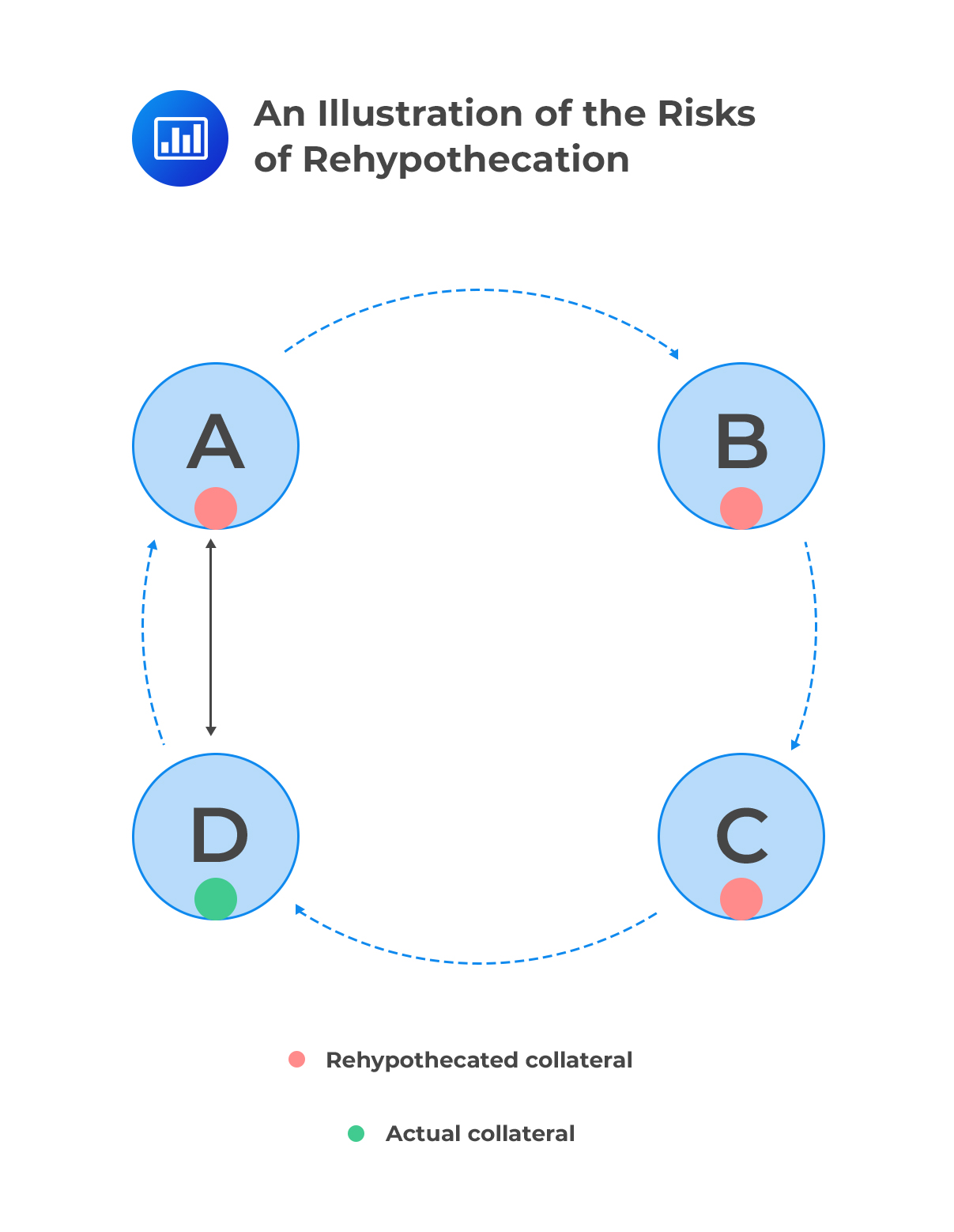

Rehypothecation, also called re-use, is the process in which one party receives collateral and then reuses it to honor their collateral obligations with another counterparty. While some assets such as cash and collateral posted under title transfer are intrinsically reusable, other types of collateral must have a right of Rehypothecation.

Although rehypothecation makes the OTC derivatives a bit more liquid, it comes with risks. Consider the case where Party A pledges collateral to Party B, but Party B subsequently rehypothecates the collateral to another party, C, with whom it has a separate trade. If Party C defaults, it means that Party B will incur a loss since it won’t receive back the collateral, particularly under a title transfer agreement. The problem doesn’t end there; Party B will still have a liability to Party A for not returning the collateral.

In short, rehypothecation can create an intricate web of potentially crippling liabilities. It was a popular practice in the lead-up to the 2007/2008 financial crisis. Recent years, however, have seen a scaling back of rehypothecation as parties increasingly prefer cash and stricter collateral management rules.

Segregation

SegregationEven in the absence of rehypothecation, the risk that collateral posted by a party may not be retrieved remains. Segregation is a legally enforceable practice that requires counterparties to return any unused collateral at the end of a contract, in priority over any bankruptcy rules. Segregation can also be achieved by placing collateral in the hands of a third-party custodian. Rehypothecation rules out segregation and vice versa.

Market risk arises in the sense that there is a likelihood of some market movements that will occur after the last posting of collateral. For example, the collateral may fall in value irreversibly, such that any haircuts in place do not entirely offset a loss. Although the market risk may not result in an actual loss, it still exposes the collateral holder to a significant loss in the event of default.

Even though collateral significantly reduces counterparty risk, elements of the credit support annex such as thresholds and minimum transfer amounts, which tend to delay the posting of collateral, mean that there’s still some residual risk.

The margin period of risk (MRP) is a term that is specific to counterparty risk and refers to the effective time between a counterparty ceasing to post collateral and when the underlying transactions have been closed-out or replaced. The period between posting and close-out or replacement is crucial because any increase in an exposure remains uncollateralized.

In the process of handling collateral, several specific operational risks emerge:

Operational risk increases as an institution engages in a higher number of trades. A bank may have thousands of OTC collateral agreements with many clients. Such a bank may post or receive collateral running into millions of shillings every day, a scenario that comes with large operational costs in terms of human and technological resources.

To reduce operational risks, the following are paramount:

Holding collateral gives rise to legal risk when the non-defaulting party attempts to seize and use collateral held to compensate for their loss after a default event.

As noted earlier, it is difficult to liquidate collateral at its market value, possibly in stressed market conditions. When a default event occurs, an institution (non-defaulting party) will usually seize assets designated as collateral, sell them for cash, and then attempt to initiate new hedges elsewhere. But selling such assets for their true worth in such circumstances is difficult. This is, especially, true for large volumes of collateral that cannot be sold without triggering some kind of a market shock that might push the price down. A party in such a situation may decide to sell the assets in smaller quantities, but that also means that it exposes itself to market volatility for a longer period.

A case of wrong-way risk where there’s a link between the value of the collateral and the counterparty’s credit quality only serves to further drive up liquidity risk.

An institution engaged in collateralized transactions faces funding liquidity risk in the sense that it may not be able to meet frequent collateral demands in line with contractual agreements. Most institutions usually do not have substantial cash reserves or liquid securities that can be leveraged quickly and posted as collateral. Segregation, if present, further clips an institution’s funding capabilities because it cannot rehypothecate collateral already held.

Collateral posted in foreign currency is prone to exchange fluctuations. Although this risk can be hedged in spot and forward markets, care must be taken to ensure that it does not result in additional risks for the institution.

Basel III acknowledges operational risk through the requirement for a larger Margin Period of Risk (MPoR) in cases where transaction counts are excessive, portfolios contain illiquid or exotic transactions difficult to value during market stress, or there is a track record of margin call disputes. A larger MPoR necessitates increased capital reserves, creating an incentive for institutions to reduce operational risk.

In the Basel II framework, banks were required to incorporate a minimum of 10 business days’ MPoR when modelling Over the Counter (OTC) derivatives. Basel III, however, adopts a more conservative stance with a baseline MPoR of 20 business days, extendable under certain conditions. This is in stark contrast to the shorter MPoR assumptions (around five business days) typically adopted by Central Counterparties (CCPs).

Achieving capital relief is mostly limited to the presence of mandatory break clauses within financial contracts. Nonetheless, if a bank consistently waives these breaks, regulators may scrutinize their effectiveness regarding risk reduction. Although challenging, capital relief may be obtained through optional breaks, but only if a bank can demonstrate strict enforcement. It is also important to note that any capital relief derivative from rating-based triggers is explicitly prohibited by the Basel capital guidelines.

While variation margins demand immediate posting, initial margin obligations are phased in with decreasing thresholds, culminating by 1 September 2021, and pertain solely to new derivatives contracts. Contracts prior to this date are exempt from such requirements. Entities may utilize a margin threshold, which permits a leeway of up to €50 million (on a group consolidated basis) before the obligation to post initial margins arises. This threshold seeks to lessen the liquidity strain exerted by these regulatory mandates.

Question

A global hedge fund enters into a master agreement with a major investment bank for a derivatives portfolio valued at USD 500 million. The master agreement contains a credit support annex (CSA) that outlines the margining terms for the collateralized portfolio, which includes a threshold of USD 150 million, a minimum transfer amount of USD 25 million, and a margin period of risk of 15 days. Based on this information, which of the following statements is accurate?

A. A reduced threshold would mean that a smaller portion of the portfolio’s exposure remains uncollateralized.

B. An extended margin period of risk suggests that a larger portion of the portfolio’s exposure remains uncollateralized.

C. A higher minimum transfer amount indicates that a greater portion of the portfolio’s exposure is safeguarded by collateral.

D. The CSA ensures consistent protection from collateral irrespective of the variations in the portfolio’s value.

Solution

The correct answer is A.

The threshold in a CSA represents the level of credit risk exposure below which no collateral is required. If the threshold is reduced, it suggests that only a lower amount of exposure will be uncollateralized, meaning a larger portion of the exposure is backed by collateral.

B is incorrect. The margin period of risk is the estimated time necessary to liquidate positions in the case of a counterparty default. A lengthier margin period of risk implies a longer duration to close out positions, but it does not have a direct correlation with the uncollateralized portion of exposure.

C is incorrect. The minimum transfer amount is the smallest amount of collateral that must be transferred between parties. A higher minimum transfer amount doesn’t inherently imply that a larger portion of the portfolio’s exposure is collateralized. Instead, it merely increases the granularity of collateral transfers.

D is incorrect. The amount of collateral specified by the CSA does not guarantee consistent protection across the lifespan of the portfolio. The protection level can fluctuate based on the portfolio’s value and other dynamic factors affecting the exposure.

Things to Remember

- MTM Relation: If the Mark-to-Market (MTM) value is below the threshold, the underlying portfolio remains uncollateralized. However, if MTM exceeds the threshold, collateral equivalent to the exceeding amount must be posted.

- Consider a contract with a threshold of $10,000. If the MTM, after a day’s market movement, reaches $12,000, then $2,000 worth of collateral would be required.

- A non-zero threshold signifies that counterparties are willing to accept a specific level of counterparty risk.

- In certain cases, the threshold may be set to zero, indicating that collateral is to be posted irrespective of the MTM value.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.