Model Risk

The objective of this chapter is to identify and explain modeling assumption errors... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

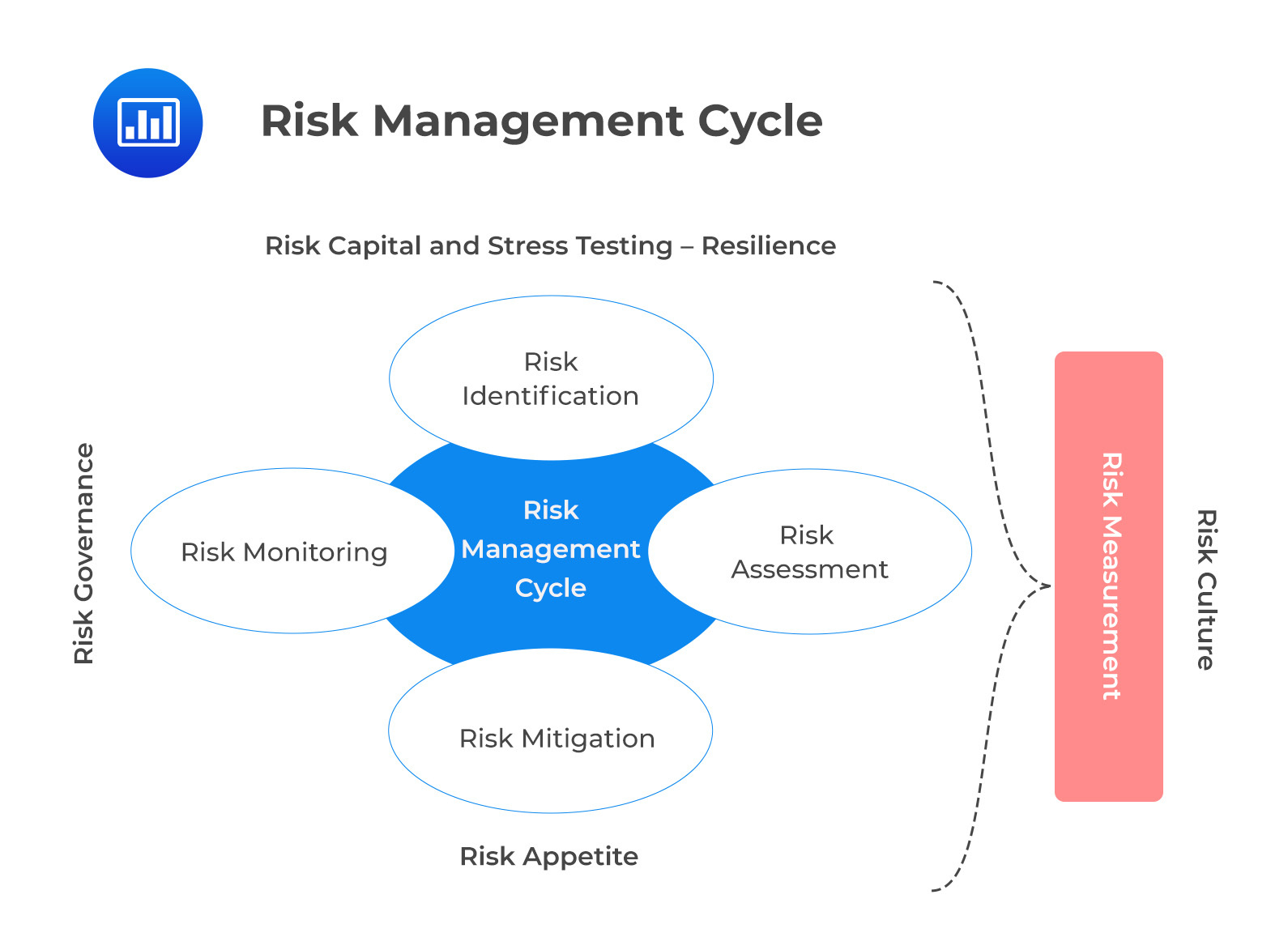

In chapters 3 to 5, we looked at the four stages of the risk management cycle: risk identification, risk assessment, risk mitigation, and risk monitoring. In chapter 4, we looked at the different quantitative approaches and models used to analyze operational risk, approaches used to determine the level of operational risk capital for economic capital purposes, and the practices for assessing operational risk and resilience. In Chapter 3, we looked at risk governance, risk culture, and risk appetite in the context of ORM. However, in this chapter, we look at these three elements in Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) context. This chapter is not a repetition of what has already been covered in the previous chapters, but it presents a wider view of risk assessment frameworks and capital assessment in the financial sector. This chapter is divided into three major sections:

The figure below presents the four stages of the risk management cycle.

Enterprise risk management is a holistic approach to risk management where all risks are viewed together within a coordinated and strategic framework. Enterprise risk management (ERM) organizes and coordinates a firm’s integrated risk management framework. It establishes policies and directives for managing risks across business units, provides the senior management with overall control and monitoring of an organization’s exposure to significant risks, and incorporates them into strategic decisions. ERM provides a broader and consistent enterprise view of risk. Therefore, it pinpoints the significant threats facing a firm’s life and its core operations.

Risk governance, risk culture, and appetite guide the ERM. Risk governance defines the roles and responsibilities of people in the three lines of defense and organizes decision-making and reporting, usually through committees. Risk culture is all about the values and behaviors of people within an organization. Risk appetite is about how much risk a firm is willing to take.

The three lines of defense define the roles and responsibilities for the overall risk management of a firm.

The first line of defense comprises the staff and management of business lines. It is responsible for making decisions for managing risks.

A risk owner is responsible for identifying, measuring, mitigating, and reporting risk. Risk owners are responsible for making decisions to ensure an appropriate balance between risk and reward for the firm. Risk owners have the authority to expose the firm to risk within the firm’s risk appetite limits.

The second line of defense is responsible for the framework and overseeing the risk management activities in the first line. The second line is responsible for establishing risk management methods, tools, models, and measurement methods, training the first line of defense, raising risk awareness, developing risk management policies, and ensuring effective risk management is implemented in the organization’s activities and decision-making. The second line of defense is also responsible for reviewing, monitoring, and testing the effectiveness of the ERM framework.

In particular, the second line of defense comprises banks’ credit risk management, market risk management, and operational risk management departments. Also included are other oversight functions, such as compliance or information security, and parts of hybrid functions, such as legal, finance, and IT.

The third line of defense oversees the risk management activities in the first and second lines. Third-line reviews are usually conducted by the firm’s internal and/or external audit teams and may also involve independent third parties. The third line of defense reports independently to the board of directors.

The board risk committee is responsible for overseeing all risks across a firm. This committee is independent of the board of directors and recommends risk-based decisions, risk exposure, and risk management to the full board. The term of reference or a committee charter governs the operations of this committee.

As we mentioned in Chapter 2, risk culture is inseparable from corporate culture and goes beyond the culture of alertness and reporting of operational risk incidents, as well as the sharing of lessons learned. From an enterprise-wide perspective, corporate culture is “what happens when no one is looking.” Corporate culture includes the values, beliefs, and behaviors that all employees adhere to under senior managers’ guidance and examples. A firm’s corporate culture directly influences its attitude and preferences when managing risks, from prudent to daring, from compliant to challenging.

Post-financial crisis reports emphasized that a lack of risk culture led to risk management failure in large financial institutions. According to the seminal paper issued by the Journal of Finance in 2013, bank holding companies with a higher lagged risk management index have lower tail risk and higher return on assets. This aligns with the hypothesis that a robust and independent risk management function can reduce tail risk exposures at banks. Other signs of a lack of risk culture include money laundering and embargo breaches. The absence of a risk culture leads to dire consequences, emphasizing the need for firms to establish and maintain a risk culture.

Risk culture influences the effectiveness of an ERM framework. It should be noted that the firm’s risk culture and governance arrangements reflect its risk appetite and tolerance.

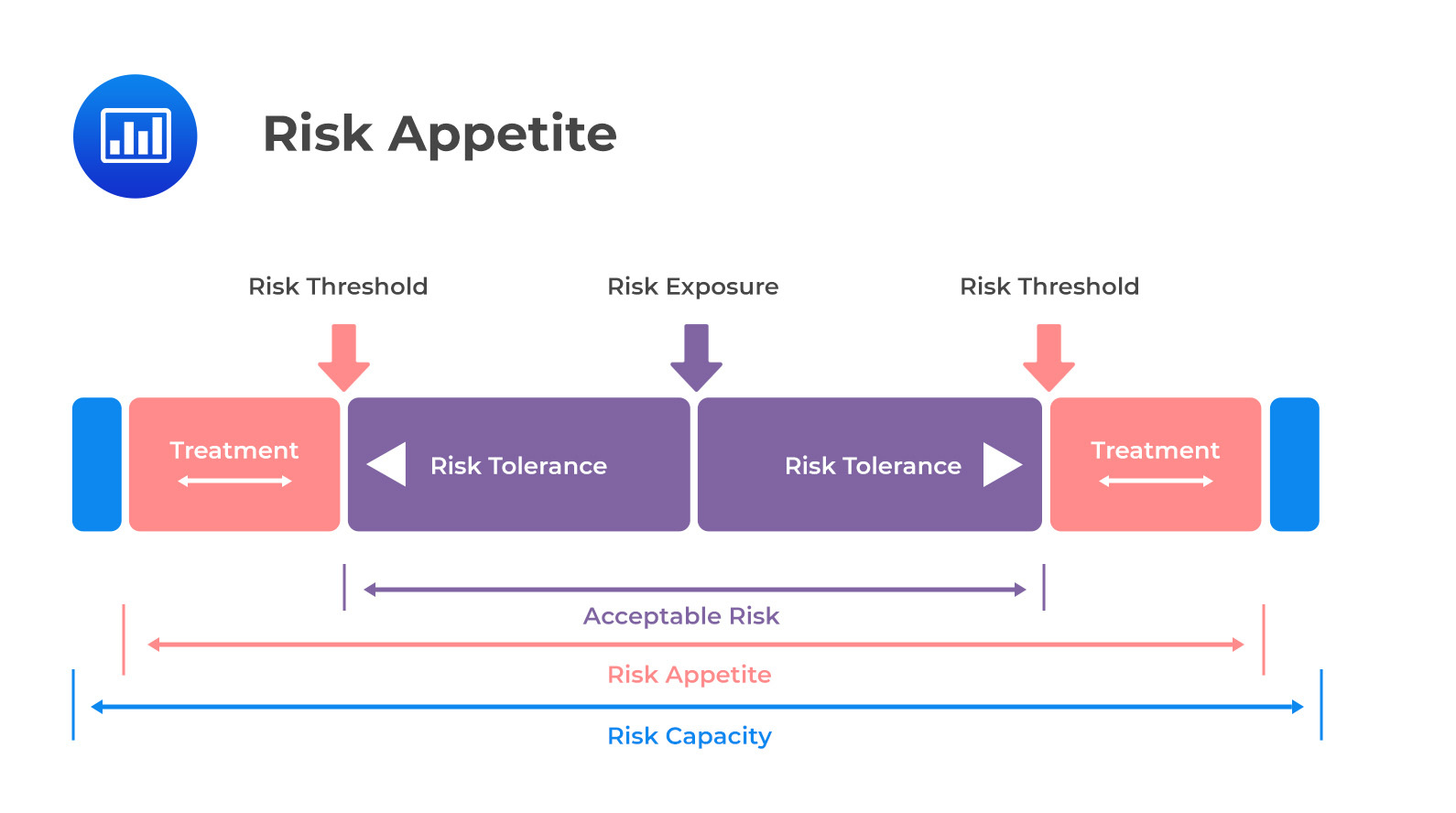

Chapter 2 discussed the structure and best practices for determining a risk appetite definition and limits for operational risk and resilience. In the next section, however, we generalize risk appetite to enterprise risk management.

Chapter 2 discussed the structure and best practices for determining a risk appetite definition and limits for operational risk and resilience. In the next section, however, we generalize risk appetite to enterprise risk management.

Risk appetite is defined as the risks a firm is willing to take to meet its objectives. In the financial industry, banks are willing to take financial risks. However, while pursuing their financial objectives, firms are also exposed to other risks such as credit, market, liquidity, and operational risks. Furthermore, these financial risks have visible return premiums, i.e., credit risk, market risk, and liquidity premiums. However, risk-taking is limited even for these visible returns.

The creation and implementation of a robust risk appetite framework is a crucial part of any risk management practice. To define a company’s risk appetite, one needs to come up with a document called a “statement of risk appetite.” This document outlines and brings together the needs of all stakeholders by acting both as a governor of risk and a driver of current and future business activity. The statement of risk covers all risks in both qualitative and quantitative aspects. A risk appetite framework is, therefore, a structure that is put in place to outline a firm’s approach to the management, measurement, and control of risk.

In addition to managing risks, another fundamental role of ERM in financial services is to ensure the solvency and sustainability of an institution through appropriate capital funding that covers any unexpected losses relating to any of the main risk classes. An enterprise risk management framework and activities consist of the following elements:

This section discusses each of these elements from an enterprise-wide view.

The Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS) was formed by the central bank governors of the Group of Ten countries, with representatives from banks in each country. As part of its responsibilities, BCBS sets guidelines for regulating and supervising banks in the G-10 countries and even non-G-10 countries. The following are the objectives of BCBS’s prudential regulation of the financial industry:

BCBS has set regulatory capital requirements to ensure the solvency and soundness of all financial intermediaries. To achieve these last two objectives, banks must meet requirements regarding their senior management’s competence and experience. In addition, banks should monitor and report on the activities of their operations.

In July 1988, Basel I recommended a minimum level of capital equivalent to 8% of the risk-weighted assets (RWA) to cover unexpected credit losses. In 1996, due to the evolution of financial market activities, Basel I extended regulatory capital to market risk using a Value at Risk (VAR) approach. In 2002, “Basel II” added regulatory capital for operational risk and reformed credit capital calculation to use counterparty credit ratings. Basel regulations bear no legal ground. Instead, countries choose to include the Basel standard through domestic laws and regulations. The Basel II reforms introduced three regulatory pillars, broadening the scope of prudential supervision.

The latest reform, “Basel III,” incorporated the lessons learned from the 2007-2009 financial crisis and introduced a minimum regulatory ratio for liquidity risks. In addition to the minimum capital requirement of 8% of RWA for banks, a buffer equivalent to 2.5% of RWA is required.

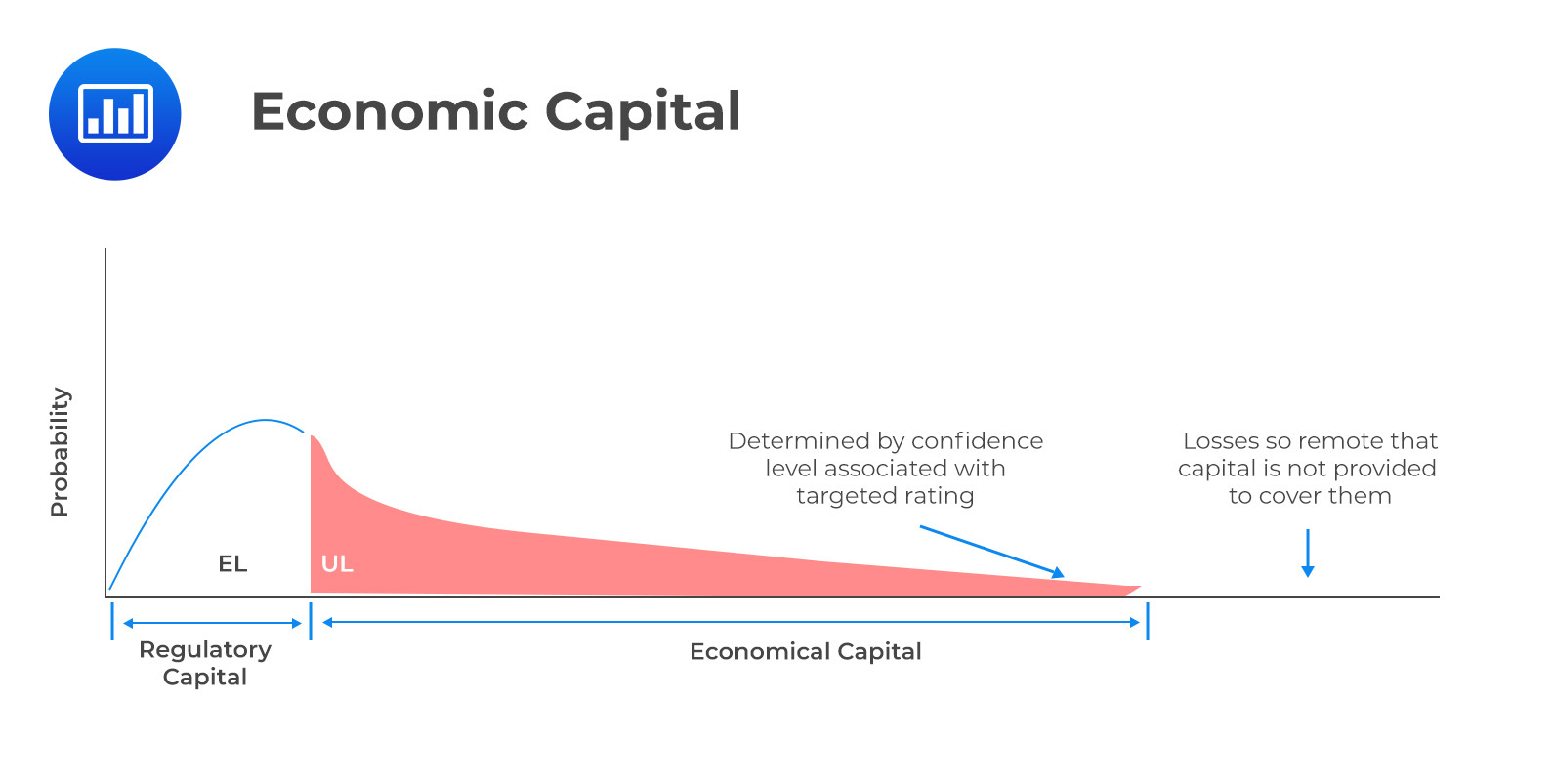

In addition to meeting regulatory capital requirements, financial intermediaries must calculate their own level of capital that reflects both their risk profile and potential needs to cover unexpected losses. The regulatory capital requirement may not fully reflect the firm’s risk profile despite the efforts of regulators, so it may not serve as a reliable measure of risk. This is more evident when standardized approaches are used under Pillar 1.

Economic capital is the amount of own funds (including equity and subordinated debt) a firm estimates will be sufficient to cover unexpected losses arising from one or more risks.

Capital requirements for banks are largely determined by their credit ratings, which influence their borrowing costs. In general, the higher the capital, the larger the buffer against losses, the better the creditworthiness of the firm, and the lower its borrowing costs. The firm’s economic capital is calculated in the same way as a VaR based on its revenue distribution, taking into account the diversification effect across all risks.

Capital requirements for banks are largely determined by their credit ratings, which influence their borrowing costs. In general, the higher the capital, the larger the buffer against losses, the better the creditworthiness of the firm, and the lower its borrowing costs. The firm’s economic capital is calculated in the same way as a VaR based on its revenue distribution, taking into account the diversification effect across all risks.

A financial firm must allocate economic capital for the risks it generates for each activity it undertakes. Capital is an expensive source of funding. In order to determine the risk-return trade-off of their products and services, large banks calculate their RAROC, which will be discussed in the next section.

RAROC is mostly used in credit risk. This section will look at it from an ERM perspective. Firms measure their profitability in the form of return on equity (ROE) or return on capital (ROC). ROC is the return on capital divided by invested capital, which is similar to ROE except that debt is included in the denominator. RAROC is a risk-adjusted version of ROE banks use to adjust for different lending types. RAROC Is given by:

$$ \text{RAROC} = \frac{\text{Expected after-tax risk-adjusted net income}}{\text{Economic capital}} $$

In contrast to ROC, RAROC adjusts net income for EL generated by risk, and the capital amount used as a denominator is economic capital or equity needed to cover risks.

RAROC is more straightforward for credit activities, while EL can be estimated using historical data. In contrast, market risk EL is less straightforward and is often set to 0. Operational risk is generally not measured with RAROC since it is difficult to attribute explicit revenues to operational risk, and economic capital is uncertain.

Different levels of granularity can be used to estimate RAROC, depending on the scope of the profitability calculation. Revenues generated by a transaction, client, portfolio, or entire business line can be defined as RAROC revenues. For expected losses (EL), these can be credited ELs on a portfolio, type of client, or business segment.

RAROC is used to:

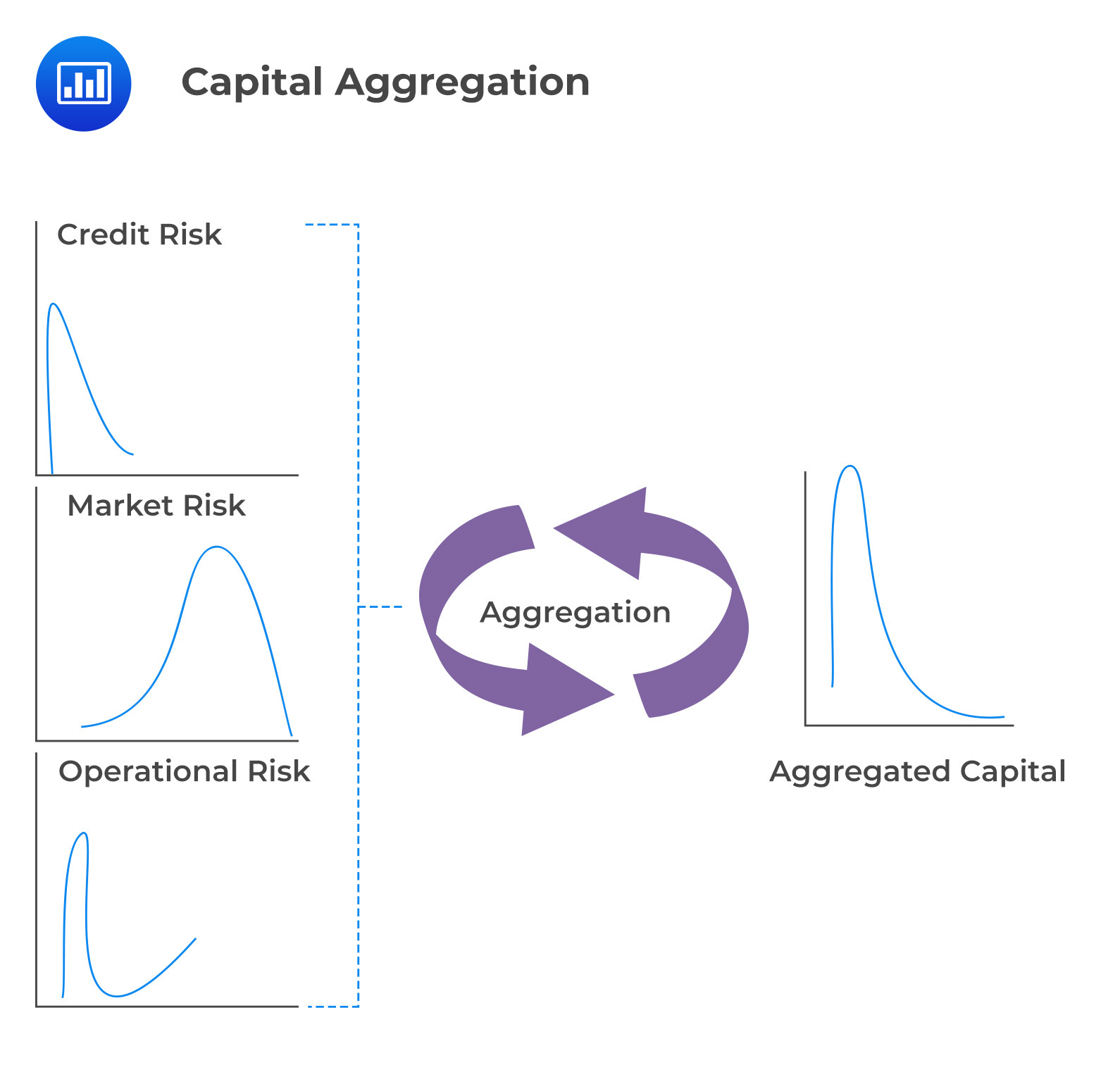

Once capital for each risk type has been identified, what follows is to assess aggregate capital needs. Since not all risks will materialize simultaneously, diversification is allowed across various risk classes: market risk, credit risk, and operational risk. Diversification can be of two types:

To determine the risk capital for a particular business unit within a larger firm, each unit is typically viewed on a stand-alone basis. The assumption that each risk category follows different dynamics could result in a low aggregated capital level compared to the sum of the stand-alone capital amounts for each risk category. The difference between these two makes up the diversification benefits. That’s because the returns correlation is likely to be less than +1. As such, the risk capital for the firm should be significantly less than the sum of the stand-alone risk capital amount for individual risk.

Operational risk, in particular, can add diversification benefits to aggregate capital because of its low correlation with other risk classes. It can be observed that credit and market risk correlations tend to increase during a crisis; operational risk, on the other hand, moves independently. This implies that we can have large diversification benefits when operational risk is aggregated with other risks.

Stress testing requires firms to estimate expected losses under extreme economic conditions while also considering idiosyncratic scenarios. However, the US has shifted its focus from the estimation of capital to stress testing operational risk as well as other risks. While both economic capital and regulatory capital are concepts of through-the-cycle, stress testing is a point-in-time process. In the next section, we discuss the basics of stress testing in the financial industry for operational risk and enterprise-wide stress testing.

Stress testing requires firms to estimate expected losses under extreme economic conditions while also considering idiosyncratic scenarios. However, the US has shifted its focus from the estimation of capital to stress testing operational risk as well as other risks. While both economic capital and regulatory capital are concepts of through-the-cycle, stress testing is a point-in-time process. In the next section, we discuss the basics of stress testing in the financial industry for operational risk and enterprise-wide stress testing.

Stress testing is simply a type of testing used to determine a system’s or an entity’s stability. In practice, it involves stressing that system or entity beyond its normal operational capacity, usually to a “breaking point,” to see what happens.

Stress tests took center stage following the 2007-2008 financial crisis. It developed as a means of assessing the ability of financial institutions to withstand adverse events. The idea was to identify and report the bank’s capital sufficiency to evade inherent failures. Stress tests have since become entrenched tools to gauge the banking sector’s resilience. The emphasis on stress tests to assess and replenish bank solvency was clarified by the fact that capital defines a bank’s to weather losses and continue to lend. Until the Great Financial Crisis, banks were limited to following the Internal Rating-Based Approach for Capital Requirements for Credit Risk under Basel II. They were required to stress test their internal rating models under different scenarios, including market risk, and liquidity conditions, among others.

BCBS released a publication in May 2009 describing why stress testing failed during the great financial crisis. It addressed the following issues:

In response to the identified stress testing weaknesses, BCBS published stress testing principles which include:

A stress testing taxonomy helps to understand the evolution of stress testing and the range of stress testing practices. It can also help banks appropriate strategies for stress-test planning and execution. We have two dimensions under the stress testing taxonomy:

In this chapter, we will discuss three types of stress testing, i.e., parameter, macroeconomic, and reverse stress testing.

Parameter/model stress testing involves testing the robustness of a model by changing the value of its parameters. It applies quantitative methods to analyze measurable risks. A model parameter is stressed to see how a model, bank, or portfolio fares under stressed conditions.

To test the financial resilience of the largest banks, macroeconomic scenarios are stressed, including inflation, unemployment, GDP changes, and foreign exchange.

Both measurable and immeasurable risks and the dependency structure are stressed in macro stress testing. It applies both quantitative and qualitative methods. This test aims at understanding how banks will fare in adverse macroeconomic conditions. This test assumes that models produce accurate projections, and its focus is on how changes in macroeconomic factors affect their output. Unlike parameter/model testing, whose quantitative analysis focuses on statistical scenarios such as a “standard deviation event,” macro stress testing seeks to estimate the outcome based on a set of macroeconomic scenarios.

Reverse stress testing usually applies qualitative methods and seeks to analyze immeasurable risks. Recall that stress testing involves generating scenarios and then analyzing their effects. Reverse stress testing starts from the opposite end and tries to identify circumstances that might cause a firm to fail.

By using historical scenarios, a bank identifies past extreme conditions. Then, the bank determines the level at which the scenario has to be worse than the historical observation to cause the bank to fail. For instance, a bank might conclude that twice the 2005-2006 US housing bubble will make the financial institution fail.

A reverse stress test primarily aims to assess operational resilience instead of determining the financial resources required to weather extreme conditions. Reverse stress testing also helps banks determine what mitigation actions and controls they need to implement and whether they need to set up triggers for future actions if the economy or the firm itself begins to follow the path of the scenarios explored.

Financial institutions have largely been practicing macro stress testing since the great financial crisis of 2007-2009. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, created macroeconomic shocks and operational shocks that far surpassed any regulatory, macroeconomic stress tests. Nowadays, operational risk stress testing involves macro testing and parameter testing and extends beyond operational risk quantification. Stress testing aims to understand how risk changes over time and with changing macroeconomic conditions. Through this understanding, banks and regulators can project losses during periods of macroeconomic stress.

Developing these stressed operational risks requires banks to establish comprehensive operational risk stress testing frameworks that make it possible for them to forecast different macroeconomic scenarios.

An operational stress testing framework should apply appropriate approaches, including regression analysis, loss distribution approach (LDA) forecasting, and scenario analysis, based on the assumption that the loss distribution curve has shifted.

The Fed initiated the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) for the largest banks. CCAR’s primary objective is to ensure that a repeat of the 2007-2009 financial crisis is avoided by regularly giving regulators better visibility into stress testing results of bank balance sheets.

A robust operational risk stress-testing framework consists of three elements to facilitate an operational risk loss forecast based on quantitative and qualitative techniques. These elements include:

When developing the methodology for the model component of the expected non-legal loss forecast module, banks have the challenge of determining whether their operational risk losses are affected by macroeconomic factors. This debate is yet to be settled. Some argue that operational risk is idiosyncratic to each bank and not influenced by macroeconomic factors.

In spite of this challenge, banks should develop a well-structured approach to linking macroeconomic conditions with operational risk losses. Banks are unlikely to find a direct correlation between all loss types and macroeconomic variables.

Banks can develop macroeconomic-based stress-testing models that model total operational risk losses or the frequency and severity of operational risk losses. In general, banks prefer modeling the frequency and severity of operational risk losses using two methodologies:

LDAs lack risk drivers; thus, they assume that a firm’s risk exposure remains the same over time. For this reason, traditional LDAs are preferred when regression models have failed to produce any results.

The above assumption of LDA does not align with the stress testing objectives, which is to understand how an organization’s risk exposure changes with time to reflect the changing microeconomic environment and the broader operating environment. The conditional LDA is a trade-off between the simple LDA and a full-blown regression-based stress test. Regression is used to model frequency, which is more sensitive to macroeconomic conditions, and its modeling is easier. On the other hand, the severity distribution is assumed to remain constant. To stress severity, a higher percentile of the distribution reflecting the firm’s expectations for average losses per event under stressed conditions is selected based on expert judgment. The selected losses are then combined with frequency forecasts through Monte Carlo simulation.

Expert judgment and data can also be combined with conditional LDA. However, it is challenging for conditional LDA to justify the severity percentile choice. The 99.9th percentile used for regulatory capital purposes is inappropriate for stress-testing purposes. A stress test aims to determine whether an institution’s capital levels are sufficient to survive a macroeconomic environment. Consequently, when the severity of losses is set at the same percentile level as capital, then a firm is always projected as undercapitalized.

Regulators have solved this issue by removing percentile requirements on stress testing. Among the stress testing principles, principle 4 addresses this issue – Stress-testing frameworks should capture material and relevant risks and apply sufficiently severe stresses.

Modeling operational risk severity proves more challenging than modeling frequency. When modeling frequency, the severity of losses is assumed to be related to macroeconomic factors; therefore, it is easier to model frequency.

On the contrary, the severity of losses is highly affected by tail events, and therefore, modeling the distribution of severity losses can be more complex. The mean of severity is thus not a comprehensive estimator, and thus this limits the ability of banks to use such an estimator. Instead, banks can choose to use the median severity or any other appropriate approach.

As with frequency, regression analysis of average loss severity is used by some banks to estimate models incorporating macroeconomic variables in order to account for adverse economic conditions. Simple linear models and log-linear models are usually employed.

Experts should refine the estimates of stressed losses using scenario analysis to ensure the model adequately covers all material risks. This is very useful, especially when dealing with operational risks with little historical data or changing unpredictable risks. To refine a model, experts and risk owners should review and challenge it to support macro drivers embedded in frequency regression. Experts should identify and discuss any changes that might invalidate the historical loss experiences based on operational risk loss expectations.

Bank holding companies (BHCs) should estimate legal costs likely to occur under baseline and stressed conditions. Even though legal losses are considered part of operational losses, they should be subdivided into their own subcategories as much as possible.

There is a challenge associated with legal risk. Legal risk is characterized by the delay between adverse macroeconomic conditions and legal losses suffered by banks. It may take years for business practices that result in litigation to materialize in actual settlement losses. Consequently, forecasts developed under this module must take into account lags between factors leading to the estimate and actual losses.

The idiosyncratic scenario add-on module is developed to cover a bank’s idiosyncratic operational risk profile and bank-specific risk exposures derived from storylines. The module should be developed based on a credible, transparent, robust process. The storylines should focus on addressing identified bank-specific vulnerabilities.

Practice Question

Which of the following best describes the integration of risk governance, risk appetite, and risk culture within an ERM framework?

A. Risk governance provides the structure, risk appetite sets the boundaries, and risk culture ensures adherence.

B. Risk appetite directs the governance, risk culture sets organizational norms, and risk governance monitors compliance.

C. Risk culture shapes risk governance, risk appetite sets organizational norms, and governance provides the feedback loop.

D. Risk governance dictates risk culture, risk appetite defines the limits, and culture reinforces governance.Solution

The correct answer is A.

Risk governance lays down the framework and protocols for risk management, defining roles and responsibilities. Risk appetite helps in establishing the thresholds of acceptable risk for the organization. Risk culture ensures that these protocols and thresholds are naturally adhered to by every employee in their daily operations.

B is incorrect. Risk appetite does not “direct” governance; rather, it provides the boundaries within which the organization operates. Additionally, while risk culture may influence organizational norms, it does not “set” them. Lastly, risk governance is more about providing structure than just monitoring compliance.

C is incorrect. Risk culture, while influential, doesn’t shape risk governance. Risk governance is established based on the organization’s strategy, objectives, and external regulatory requirements. Risk appetite, on the other hand, defines the boundaries of acceptable risk and doesn’t just set organizational norms. Also, governance doesn’t merely provide a feedback loop; it’s the overarching structure.

D is incorrect. Risk governance does not “dictate” risk culture. Instead, governance provides structure, while culture is more about behavior and mindset. Risk appetite indeed defines the limits, but risk culture does not reinforce governance. Rather, a strong risk culture ensures that governance and risk appetite are adhered to in daily operations.

Things to Remember

- The harmony between risk governance, risk appetite, and risk culture is pivotal for consistent risk management across all levels of an organization.

- Discrepancies or inconsistencies between these components can lead to vulnerabilities or blind spots in risk management.

- Periodic reviews of the interplay between these three components are essential to ensure that the organization remains agile and responsive to the evolving risk landscape.

- Organizations that prioritize this integration often achieve better alignment with strategic objectives and are better poised to navigate uncertainties.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.