CVA (Part A)

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Explain the motivation for... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

The term credit risk describes the risk that arises from nonpayment or rescheduling of any promised payment. It can also arise from credit migration – events related to changes in the credit quality of the borrower. These events have the potential to cause economic loss to a bank.

The expected loss is the amount a bank anticipates to lose, on average, over a predetermined period when extending credits to its customers. Unexpected loss is the volatility of credit losses around its expected loss.

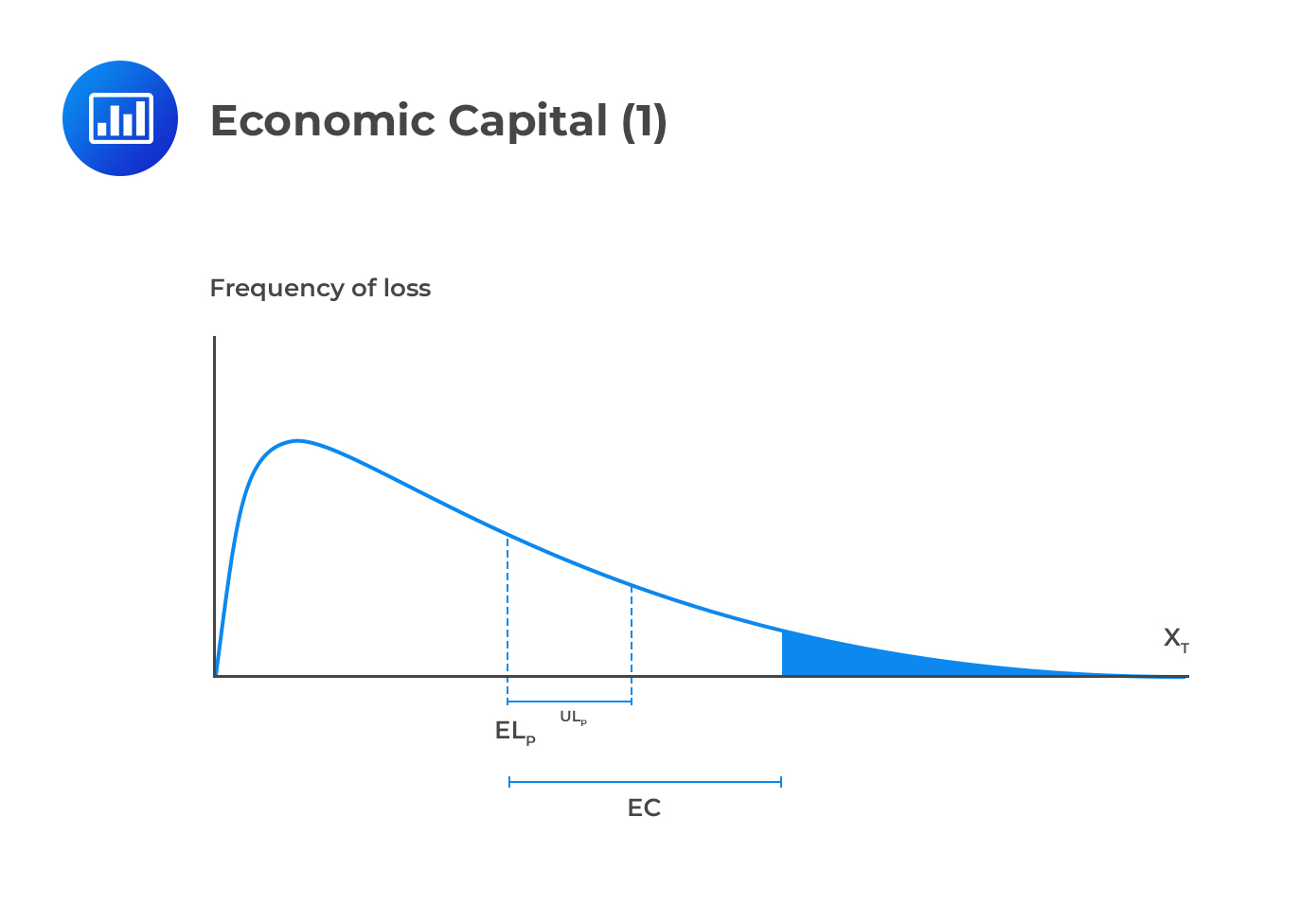

Once a bank determines its expected loss, it sets aside credit reserves in preparation. However, for unexpected loss, a bank must estimate the excess capital reserves needed subject to a predetermined confidence level. This excess capital needed to match a bank’s estimate of unexpected loss is known as economic capital.

To safeguard its long-term financial health, a lender must match its capital reserves with the amount of credit risk borne. Economic capital is largely determined by (I) level of confidence, and (II) level of risk. An increase in any of these two parameters causes the economic capital also to increase.

The probability of default (PD), describes the possibility that a borrower will default on contractual payments before the end of a predetermined period. This probability is not the greatest concern to a lender because a borrower may default but bounce back and settle the missed payments soon afterward, including any imposed penalties. It’s expressed as a percentage.

Exposure amount (EA), also known as exposure at default (EAD), is the loss exposure of a bank at the time of a loan’s default, expressed as a dollar amount. It’s the predicted amount of loss in case a borrower defaults.

EAD is a dynamic amount that keeps on changing as a borrower continues to make payments.

The loss rate, also known as the loss given default (LGD), is the percentage loss incurred if a borrower defaults. It can also be described as the expected loss expressed as a percentage. The loss rate is the amount that’s impossible to recover after selling (salvaging) the underlying asset following a default event.

The LGD can also be expressed as:

$$ \text{LGD} = 1 – \text{Recovery Rate} $$

The expected loss, \(EL\), is the average credit loss that we would expect from an exposure or a portfolio over a given period. It’s the anticipated deterioration in the value of a risky asset. In mathematical terms,

$$ EL=EA \times PD \times LGD $$

Credit loss levels are not constant but rather fluctuate from year to year. The expected loss represents the anticipated average loss that can be determined statistically. A business will normally have a budget for the \(EL\) and try to bear the losses as part of the normal operating cash flows.

Exam tip: The expected loss of a portfolio is equal to the summation of expected losses of individual losses.

$$ EL_P=\sum EA_i \times PD_i \times LGD_i $$

Unexpected loss is the average total loss over and above the expected loss. It’s the variation in the expected loss, and it is calculated as the standard deviation from the mean at a certain confidence level.

Let \({ UL }_{ H }\) denote the unexpected loss at the horizon for asset value \({ V }_{ H }\). Then,

$$ { UL }_{ H }\equiv \sqrt { var\left( { V }_{ H } \right) } $$

You will usually apply the following formula to determine the value of the unexpected loss:

$$ UL=EA\times \sqrt { PD\times { \sigma }_{ LR }^{ 2 }+{ LR }^{ 2 }\times { \sigma }_{ PD }^{ 2 } } $$

Where:

$$ { \sigma }_{ PD }^{ 2 }=PD\times \left( 1-PD \right) $$

since default is a Bernoulli variable with a binomial distribution.

A Canadian bank recently disbursed a CAD 2 million loan of which CAD 1.6 million is currently outstanding. According to the bank’s internal rating model, the beneficiary has a 1% chance of defaulting over the next year. In case that happens, the estimated loss rate is 30%. The probability of default and the loss rate have standard deviations of 6% and 20%, respectively.

Determine the expected and unexpected loss figures for the bank.

Solution

$$ EL=EA \times PD \times LR $$

\(EA=CAD 1,600,000 \)

\(PD=1\%\)

\(LR=30\%\)

Therefore,

$$\begin{align*} EL&=1,600,000\times 0.01 \times 0.3=\text{CAD 4,800}\\ UL&=EA\times \sqrt { PD\times { \sigma }_{ LR }^{ 2 }+{ LR }^{ 2 }\times { \sigma }_{ PD }^{ 2 } } \\&=1,600,000\times \sqrt { 0.01\times { 0.2 }^{ 2 }+{ 0.3 }^{ 2 }\times { 0.06 }^{ 2 } } \\& =\text{CAD 43,052} \end{align*}$$

When evaluating the variance of the default probability, a binomial distribution framework is utilized due to the binary outcome of a default event. In this context, default is modeled as a Bernoulli process with two outcomes:

For \( n\) independent loans or credit exposures, the number of defaults can follow a binomial distribution, and the variance of the number of defaults is computed using the binomial distribution variance formula:

$$ \text{Var(X)}= n \cdot PD \cdot (1 – PD) $$

Where:

\(X=\) random variable representing the number of defaults

\(n=\) total number of loans or exposures

\(PD=\) probability of default per loan.

The expression \(PD \cdot (1 – PD)\) captures the inherent volatility of the default process for an individual loan.

Understanding the computation of this variance is crucial for the FRM exam, as it is integral to calculations of unexpected loss (UL) and the assessment of economic capital for credit risk.

Consider a portfolio with 10,000 loans, with each loan having a probability of default of 1%. What is the variance of the probability of default for this portfolio?

$$\begin{align}Var(X)&= n\cdot PD \cdot (1 – PD)\\&=10,000\times 0.01\times(1-0.01)=99\end{align} $$

Unlike expected loss, we do not compute the unexpected loss of a portfolio by summing up the unexpected loss of individual assets. And this is because the standard deviation of the sum will not be the same as the sum of standard deviation unless there is a perfect correlation.

Given a portfolio with \(N\) assets, the unexpected loss is given by:

$$ { UL }_{ P }=\sqrt{\left[ \sum _{ i }^{n } \sum _{ j }^{ n }{ { \rho }_{ ij }{ UL }_{ i }{ UL }_{ j } } \right]} $$

For a two-asset portfolio:

$$ { UL }_{ P }=\sqrt { { UL }_{ i }^{ 2 }+{ UL }_{ j }^{ 2 }+2\rho { UL }_{ i }{ UL }_{ j } } $$

Where:

$$ { UL }_{ x }={ EA }_{ x }\times \sqrt { { PD }_{ x }\times { \sigma }_{ { LR }_{ x } }^{ 2 }+{ \left( LR \right) }_{ x }^{ 2 }\times { \sigma }_{ { PD }_{ x } }^{ 2 } } \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad x=i\quad or\quad j $$

And \({ \rho }_{ ij }\) is the correlation of default between asset \(i\) and asset \(j\).

Therefore, if \({ \rho }_{ ij }=1\) for \(i\neq j\), that’s the only instance when the unexpected loss of a portfolio will be equal to the sum of the unexpected individual losses.

Due to the effects of diversification (elimination of specific risks), the risk of a portfolio is always less than the total risk of assets held separately. It follows that the unexpected loss for a portfolio is much less than the sum of unexpected individual losses.

The risk contribution of a risky asset, I, to the unexpected portfolio loss, also called the unexpected loss contribution, ULCC, is defined to be the incremental risk that the exposure of a single asset contributes to a portfolio’s total risk.

The risk of a given portfolio is considerably less than the sum of the individual risk levels because each asset contributes only a portion of its unexpected loss in the portfolio. This effect is captured by the partial derivative of ULp (portfolio unexpected loss) with respect to ULi (unexpected loss from asset i), i.e.,

$$ ULC_{ i }=UL_{ i }\times \frac { \delta UL_P }{ \delta UL_i } $$

After differentiation, and assuming that the portfolio consists of n loans, it can be shown that the risk contribution of a particular asset is given by:

$$ ULC_{ i }=\frac { UL_{ i }\sum _{ j=1}^{ n }{ UL_j\rho_{ij} } }{ UL_P } $$

Where:

\(ULC_{ i }\) = Unexpected loss contribution of asset i.

\(UL_{ i }\) = Unexpected loss from asset i.

\(UL_{ j }\) = Unexpected loss from asset j.

\(\rho_{ ij }\) = Correlation between asset i and j where i \(\ne\) j.

\(UL_{ P }\) = Unexpected loss from the portfolio.

For a two-asset portfolio, we can calculate the risk contribution of each asset as follows:

$$\begin{align*} { RC }_{ 1 }&={ UL }_{ 1 }\times \frac { { UL }_{ 1 }+\left( { { \rho }_{ 12 }\times UL }_{ 2 } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } }\\ { RC }_{ 2 }&={ UL }_{ 2 }\times \frac { { UL }_{ 2 }+\left( { { \rho }_{ 12 }\times UL }_{ 1 } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } } \end{align*}$$

Where:

$$ { RC }_{ 1 }+{ RC }_{ 2 }={ UL }_{ P } $$

Risk contribution is a measure of the systematic risk of an asset in a portfolio – the amount of credit risk which cannot be eliminated by placing the asset in a portfolio.

Assuming that a portfolio consists of n loans that have approximately the same characteristics and size (1/n), we can set \(\rho_{ ij }\) = \(\rho\) = constant (for all i \(\ne\) j). In this case, the unexpected loss contribution of asset i can be given by:

$$ ULC_{ i }= UL_i \times \sqrt{ \rho }$$

Where:

$$ \sqrt{ \rho } = \frac { \sum _{ j=1 }^{ n }{ UL_j\rho_{ij} } }{ UL_P } $$

Prime Bank has two outstanding loans with a correlation of 0.4. Other characteristics are as shown below:

$$ \begin{array}{|l|r|r|} \hline \text{} & \textbf{Asset X} & \textbf{Asset Y} \\ \hline \text{EA} & $30,000,000 & $12,000,000 \\ \text{PD} & \text{0.5%} & \text{1.0%} \\ \text{LR} & \text{40%} & \text{30%} \\ { \sigma }_{ PD } & \text{3%} & \text{4%} \\ { \sigma }_{ LR } & \text{20%} & \text{30%} \\ \hline \end{array} $$

Compute ELP, ULP, and the risk contribution of each asset.

Step 1: Computing the EL for Each Asset

$$\begin{align*} EL_X &= EA × PD × LR\\& = $30,000,000 × 0.005 × 0.4 \\&= $60,000 \end{align*}$$

$$ \begin{align*}EL_Y &= EA × PD × LR\\ &= $12,000,000 × 0.01 × 0.3\\ &= $36,000 \end{align*}$$

Step 2: Computing Unexpected Loss, UL, for Each Asset

$$ UL=EA\times \sqrt { PD\times { \sigma }_{ LR }^{ 2 }+{ LR }^{ 2 }\times { \sigma }_{ PD }^{ 2 } }$$

$$\begin{align*}UL_{X}&=30,000 \sqrt { 0.005\times { 0.2 }^{ 2 }+{ 0.4 }^{ 2 }\times { 0.03 }^{ 2 } }\\&= 556,417 \end{align*}$$

$$ \begin{align*}UL_{Y}&=12,000 \sqrt { 0.01\times { 0.3 }^{ 2 }+{ 0.3}^{ 2 }\times { 0.04 }^{ 2 } }\\ &=387,732 \end{align*}$$

Step 3: Computing Portfolio Expected Loss, ELP

$$\begin{align*} EL_P&=$60,000+$36,000\\ &=96,000 \end{align*}$$

Step 4: Computing Portfolio Unexpected Loss, ULP

$$ \begin{align*}{ UL }_{ P }&=\sqrt { { UL }_{ i }^{ 2 } + { UL }_{ j }^{ 2 }+2\rho { UL }_{ i }{ UL }_{ j } }\\ & =\sqrt { { 556,417}^{ 2 }+{ 387,732 }^{ 2 }+2 \times 0.4 \times 556,417 \times 387,732 }\\&= 795,317 \end{align*}$$

Note: This actually proves that ULP < ULX + ULY thanks to diversification ($795,317 < $556,417 + $387,732)

Step 5: Computing the risk Contribution, ULC, for Each Asset

$$\begin{align*} { ULC }_{ X }&={ UL }_{ X }\times \frac { { UL }_{ X }+\left( { { \rho }_{ XY }\times UL }_{ Y } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } }\\ &={ 556,417 }\times \frac { { 556,417 }+\left( { { 0.4 }\times 387,732 } \right) }{ { 795,317 } } \\ &= 497,784 \end{align*}$$

Note: ULCX < ULX

$$\begin{align*} { ULC }_{ Y }&={ UL }_{ Y }\times \frac { { UL }_{ Y }+\left( { { \rho }_{ XY }\times UL }_{ X } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } }\\ &={ 387,732 }\times \frac { { 387,732 }+\left( { { 0.4 }\times 556,417 } \right) }{ { 795,317 } }\\ &= 297,532 \end{align*}$$

Again, note that ULCY < ULY

We can also compute ULCY as $795,317 – $497,784 = $297,533 since ULCP = ULCX + ULCY

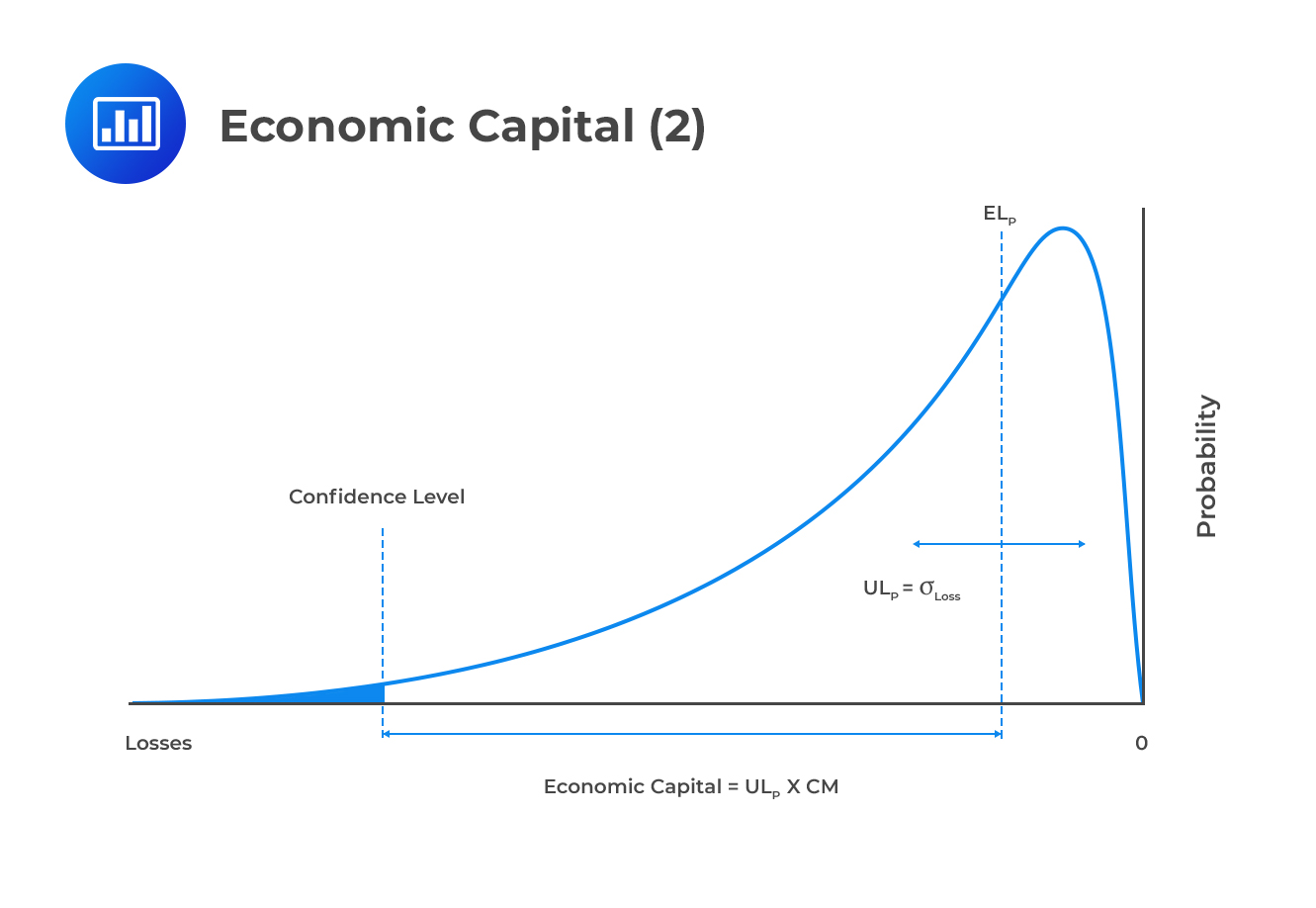

As we saw earlier, economic capital, EC, is the amount of capital needed to match a bank’s unexpected losses. The amount of EC needed is the distance between the unexpected outcome and the expected outcome, for a given level of confidence.

Let \({ X }_{ T }\) be the random variable for loss and \(z\), the percentage probability (confidence level). If we go further and let \(v\) be the minimum economic capital needed to keep the bank solvent at the time horizon \(t\), then:

Let \({ X }_{ T }\) be the random variable for loss and \(z\), the percentage probability (confidence level). If we go further and let \(v\) be the minimum economic capital needed to keep the bank solvent at the time horizon \(t\), then:

$$ Pr\left[ { X }_{ T }\le v \right] =z $$

\(z\) can be interpreted as the desired rating for the bank, say, 99.97% for an AA rating.

Given the desired level of \(z\), we want to determine the amount of EC such that:

$$ Pr\left[ { X }_{ t }-{ EL }_{ P }\le EC \right] =z $$

Define the capital multiplier, CM, by:

$$ EC=CM\times { UL }_{ P }\quad \quad \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \left( Very\quad important \right) $$

Then,

$$ Pr\left[ \frac { { X }_{ T }-{ EL }_{ P } }{ { UL }_{ P } } \le CM \right] =z $$

When modeling credit risk, analysts are interested in the left tail of the chosen loss distribution. And that’s because focus is on credit loss. Normal distribution is not appropriate for this purpose for two main reasons:

For these reasons, the favored distribution for credit risk analysis is the beta distribution. The following is its density function:

$$ F\left( x,\alpha ,\beta \right) =\begin{cases} \frac { \Gamma \left( \alpha +\beta \right) }{ \Gamma \alpha \Gamma \beta } { x }^{ \alpha -1 }{ \left( 1-x \right) }^{ \beta -1 },0<x<1 \\ 0\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad otherwise \end{cases} $$

\(Mean=\frac { \alpha }{ \alpha +\beta } \)

\(Variance=\frac { \alpha \beta }{ { \left( \alpha +\beta \right) }^{ 2 }\left( \alpha +\beta +1 \right) } \)

As can be seen in the density function above, the mass of the beta distribution lies between 0 and 1. It follows that when modeling credit events, losses are defined between 0% and 100%. Why exactly is beta distribution chosen?

The answer to that question is that beta distribution is extremely flexible. Depending on the values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), the distribution can be symmetrical or skewed. In fact, in the event that these two parameters are equal, then the expected loss for a portfolio equals its unexpected loss.

When modeling the very extreme losses, however, the credit loss distribution can be quite difficult to model using the beta distribution by itself. In such instances, Monte Carlo simulation techniques come in handy.

Practice Questions

Question 1

Big Data Inc., a U.S. based cloud technology and computing firm, has been offered a USD 10 million term loan fully repayable in exactly two years. The bank behind the offer estimates that it will be able to recover 65% of its exposure if the borrower defaults, and the probability of that happening is 0.8%. The bank’s expected loss one year from today is closest to:

A. USD 52,000.

B. USD 26,000.

C. USD 14,000.

D. USD 28,000.

The correct answer is D.

$$ EL=EA \times PD \times LR $$

\(EA=\text{USD 10,000,000}\)

\(PD=0.8\%\)

\(LR=35\%\)

$$ EL=10,000,000 \times 0.008 \times 0.35=\text{USD 28,000 }$$

Maturity is irrelevant since the loan is fully repayable in two years.

A is incorrect. The loss given default is taken to be 65%. Note that \(LGD = 1 – \text{Recovery rate}\).

B is incorrect. The loss given default is taken to be 65% and the final result dividend by two.

C is incorrect. The final result is incorrectly divided by 2.

Question 2

A bank has two assets outstanding, denominated in U.S. dollars. The correlation between the two assets is 0.4. Other details are as follows:

$$ \begin{array}{|l|l|l|} \hline {} & \textbf{Asset A} & \textbf{Asset B} \\ \hline EA & 1,600,000 & 2,000,000 \\ \hline PD & 1\% & 2\% \\\hline LR & 30\% & 40\% \\\hline { \sigma }_{ PD } & 6\% & 8\% \\\hline { \sigma }_{ LR } & 20\% & 25\% \\\hline \end{array} $$

Calculate the unexpected loss of the portfolio as well as the risk contribution of each asset:

$$ \begin{array}{|l|l|l|l|} \hline {} &\textbf{Unexpected loss} &\textbf{Risk Cont. A} &\textbf{Risk Cont. B} \\ \hline A. & 118,350 & 18,350 & 100,000 \\\hline B. & 125,800 & 102,600 & 23,200 \\\hline C. & 120,000 & 98,000 & 22,000 \\ \hline D. & 119,308 & 29,302 & 90,006 \\ \hline \end{array}$$

The correct answer is D.

For a two-asset portfolio:

$$ { UL }_{ P }=\sqrt { { UL }_{ i }^{ 2 }{ +UL }_{ j }^{ 2 }+2\rho { UL }_{ i }{ UL }_{ j } } \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots equation\quad 1 $$

Where:

$$ { UL }_{ x }={ EA }_{ x }\times \sqrt { { PD }_{ x }\times { \sigma }_{ { LR }_{ x } }^{ 2 }+{ \left( LR \right) }_{ x }^{ 2 }\times { \sigma }_{ { PD }_{ x } }^{ 2 } } \quad \quad \quad \quad \text{ x=A or B}$$

For asset \(A\),

$$ \begin{align*}{ UL }_{ A }&=1,600,000\times \sqrt { { 0.01\times 0.2 }^{ 2 }+{ 0.3 }^{ 2 }\times { 0.06 }^{ 2 } }\\&=\text{USD 43,052}\end{align*}$$

For asset \(B\),

$$\begin{align*} { UL }_{ B }&=2,000,000\times \sqrt { { 0.02\times 0.25 }^{ 2 }+{ 0.4 }^{ 2 }\times { 0.08 }^{ 2 } }\\&=\text{USD 95,373}\end{align*}$$

We can now compute the unexpected loss of the portfolio using equation 1:

$$ \begin{align*}{ UL }_{ P }&=\sqrt { { 43,052 }^{ 2 }+{ 95,373 }^{ 2 }+2\times 0.4\times 43,052\times 95,373 }& =\text{USD 119,308}\end{align*}$$

To determine the risk contributions of \(A\) and \(B\), recall the formulas:

$$ \begin{align*}{ RC }_{ 1 }&={ UL }_{ 1 }\times \frac { { UL }_{ 1 }+\left( { { \rho }_{ 12 }\times UL }_{ 2 } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } }\\ { RC }_{ 2 }&={ UL }_{ 2 }\times \frac { { UL }_{ 2 }+\left( { { \rho }_{ 12 }\times UL }_{ 1 } \right) }{ { UL }_{ P } } \end{align*}$$

Therefore,

$$\begin{align*}{ RC }_{ A }&=43,052\times \frac { 43,052+0.4\times 95,373 }{ 119,308 } \\&=\text{USD 29,302}\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{ RC }_{ B }&=95,373\times \frac { 95,373+0.4\times 43,052 }{ 119,308 } \\&=\text{USD 90,006}\end{align*} $$

Note: \(29,302+90,006=119,308\)

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.