Exchanges and OTC Markets

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Describe how exchanges can... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

An interest rate swap is an agreement to exchange one stream of interest payments for another, based on a specified principal amount, over a specified period of time. The principal in an interest rate swap is known as a notional principal because it is not exchanged. Only interest rates calculated with respect to the notional principal can be exchanged.

Assume two parties, A and B. Party A, agree to pay Party B a fixed interest rate at 4% per annum, compounded semiannually, on a principal of USD 100,000. Party B, in return, agrees to pay party A interest at the six-month LIBOR (London Inter-Bank Offered Rate). Exchanges occur every six months over a period of three years. The tables below summarize the possible scenarios of parties A and B.

Scenarios for party B: Pays LIBOR and receives a fixed rate.

$$ \begin{array}{c|c|c|c|c} \textbf{Time } & \textbf{6-month} & \textbf{Floating } & \textbf{Fixed} & \textbf{Net}\\ \textbf{in Years} & \textbf{LIBOR} & \textbf{amount} & \textbf{amount} & \textbf{cashflow} \\ \textbf{ } & \textbf{(% per year)} & \textbf{paid (USD)} & \textbf{received (USD)} & \textbf{(USD)} \\ \hline 0.0 & 3.00 & & & \\ 0.5 & 3.20 & 1500 & 2000 & +500 \\ 1.0 & 3.44 & 1600 & 2000 & +400 \\ 1.5 & 4.00 & 1720 & 2000 & +280 \\ 2.0 & 4.30 & 2000 & 2000 & –\\ 2.5 & 4.44 & 2150 & 2000 & -150 \\ 3.0 & 4.70 & 2220 & 2000 & -220 \end{array} $$

Note: The exchange takes place one period after the LIBOR is observed. Therefore, the first exchange occurring after six months will occur using the LIBOR rates observed at time zero. The exchange after one year will take place after the LIBOR rates observed at time 0.5 into the contract, and so forth.

At time 0.5, the floating rate amount will be \(3\%×0.5×100,000 = 1,500\).

The fixed-rate amount will be \(4\%×0.5×100,000= 2,000\).

As such, the cash flows exchanged will be the netted amount, \(2,000 – 1,500 = 500\).

The above calculations are just approximations as they do not consider day counts. For more accurate results, it is important to consider day count conventions.

Suppose that the exchanges in the above example take place on 1st January and 1st July. The first cash flow exchange is on 1st July of that year, and the floating rate exchanged will be: $$ \frac{183}{360} × 3\% × 100,000 = 1,525 $$

Note: 183 was obtained by adding the total number of days between 1st January and 1st July, and the day count convention for LIBOR is actual/360.

It is important to see that 1,525 is 25 more than the approximate value shown in the table (1,500).

Similarly, the fixed rate will be expressed with day count conventions as shown below:

$$ \frac{183}{360} × 4\% × 100,000 = 2,033.33 $$

Again, 2033.33 is USD 33.33 more than the approximate value shown in the table (2,000).

Interest rate swaps can be used to transform assets into liabilities, or vice-versa, by converting fixed (floating) rates loans and liabilities into floating (fixed) rates.

Assume that the 3-year bid and ask quotes are 3.06% and 3.09%, respectively. A company borrows a bank USD 5,000 at a fixed interest rate of 4%, compounded quarterly. To convert this fixed-rate loan into a floating-rate liability, the company can use the three-year bid and ask quotes to enter into a three-year swap with another company. It will then have three sets of cash flows:

The net out interest payment will therefore be:

$$ 4\% + \text{LIBOR} – 3.06\% =0.94\%+ \text{LIBOR}$$

The company will then have converted a 4% fixed interest rate into a 0.94% + LIBOR floating interest rate.

Suppose the above company borrowed USD 5,000 on a floating interest rate of three months LIBOR plus 0.5% (50 basis points). To convert the floating rate to a fixed rate, the company can use the ask quote of 3.09%. It will then have the below set of cash flows:

The net out interest payment will therefore be:

$$ \text{LIBOR} + 0.5\% – \text{LIBOR}+ 3.09\% =3.59\% $$

The company will then have converted a floating interest rate of LIBOR + 50 basis points into a fixed interest rate of 3.59%.

Assets with floating (fixed) interest rates can be converted to fixed (floating) interest rates using the same concept.

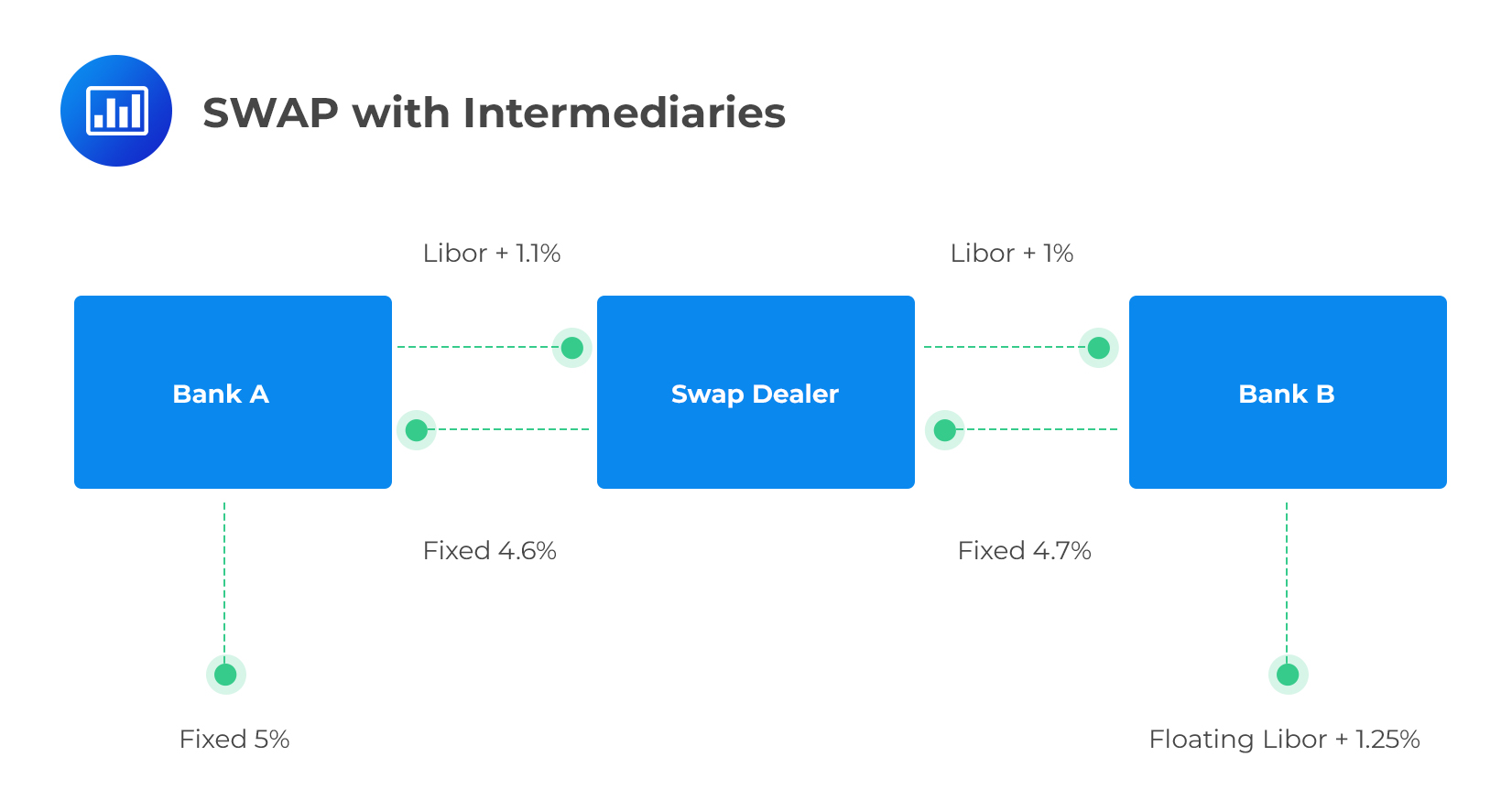

Just like in other OTC instruments, parties to a swap do not interact one-one-on-one. A swap dealer intertwines themselves between the parties taking a commission on the trade.

In most cases, therefore, a swap party stays unaware of the identity of the party in the offsetting position. The swap dealer effectively serves as an intermediary.

In most cases, therefore, a swap party stays unaware of the identity of the party in the offsetting position. The swap dealer effectively serves as an intermediary.

The details of each swap agreement are contained in a document called the confirmation. Such documents are drafted by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). Each party must append their signature on the confirmation to show their commitment to the agreement.

The contents of confirmation include the dates when payments will be exchanged, the day count conventions to be used in calculating payments, and the way payments will be calculated.

When using an overnight rate (which will replace swaps as discussed in the chapter on Properties of Interest Rates), the floating rate can be obtained using the formula:

$$ R = (1+d_1 r_1) (1+d_2 r_2) … (1+d_n r_n) – 1 $$

Where:

R is the floating rate,

d is the number of days, and

r is the overnight rate.

Apart from weekends and holidays, d = 1. Weekends and holidays lead to the overnight rate being applied more than once. On a Friday, for example, d=3.

Let’s look at an example of two firms, \(A\) and \(B\).

$$ \textbf{Borrowing costs} $$

$$ \begin{array}{c|c|c} \textbf{Firm} & \textbf{Fixed borrowing} & \textbf{Floating borrowing} \\ \hline \text{A} & 6\% & \text{LIBOR} \\ \hline \text{B} & 8\% & \text{LIBOR + 100bps} \\ \end{array} $$

From the table, we can see that \(A\) can borrow fixed at \( 6\%\), and \(B\) can borrow fixed at \(8\%\). Also, \(A\) can borrow floating at LIBOR, and \(B\) can borrow floating at LIBOR + 100bps. However, the difference in borrowing rates for \(A\) and \(B\) is higher in the fixed market than in the floating market (200bps vs. 100bps). Therefore, \(A\) has an absolute advantage in both markets but a comparative advantage in the fixed market. \(B\), on the other hand, has a comparative advantage in the floating market.

When a comparative advantage exists, the implication is that the parties involved can reduce their borrowing costs by entering into a swap agreement. The net borrowing savings by entering into a swap is the difference between the differences, i.e., \(\Delta \text{fixed} -\Delta \text{floating}\).

If we assume that the net borrowing savings are split evenly between the parties, we will divide the total borrowing savings by 2,i.e.,

$$ \text{Borrowing savings per party}=\frac { \Delta \text{fixed} -\Delta \text{floating} }{ 2 } =\frac { 200bps-100bps }{ 2 } =50bps $$

A problem with the comparative advantage argument is that it assumes the floating rates will remain in force in the long term. In practice, the floating rate is reviewed at 6-month intervals and may increase or decrease to reflect the borrower’s credit risk. It also assumes zero transaction costs even when an intermediary is involved in the swap (which is standard practice).

In essence, a swap is a series of cash flows, and therefore its value is determined by discounting all those cash flows to the present (valuation date). The cash flows are discounted using spot rates developed using the swap curve. The curve makes use of the following relationship between forward rates and spot rates, assuming continuous compounding:

$$ { R }_{\text{forward}}={ R }_{ 2 }+\left( { R }_{ 2 }-{ R }_{ 1 } \right) \frac { { T }_{ 1 } }{ { T }_{ 2 }-{ T }_{ 1 } } $$

Where:

\({ R }_{ i }\)= spot rate corresponding with \({ T }_{ i }\) years

\({ R }_{\text{forward}}\)= forward rate between \({ T }_{ 1 }\) and \({ T }_{ 2 }\)

In essence, the pay fixed, receive floating party has a long position in a floating rate (since it’s an inflow) and a short position in the fixed-rate (since it’s an outflow). The pay floating, receive fixed party has a short position in the floating rate (since it’s an outflow) and a long position in the fixed-rate (since it’s an inflow).

If we denote the value of the swap as \({ V }_{ swap }\), the present value of fixed-leg payments as \({ P }_{ fix }\), and the present value of floating-leg payments as \({ P }_{ flt }\), then:

To the pay fixed, receive floating,

$$ { V }_{\text{swap} }={ P }_{\text{flt}}-{ P }_{\text{fix} } $$

To the pay floating, receive fixed,

$$ { V }_{\text{swap}}={ { P }_{\text{fix}}-P }_{\text{flt}} $$

The important thing to note here is that the two positions are mirror images of each other.

A currency swap works much like an interest rate swap, but there are several key differences:

Currency swaps can be used to:

Two companies can also get into a currency swap to exploit their comparative advantages regarding borrowing in different currencies. For example,

If \(X\) wants to borrow \(£\), and \(Y\) wants to borrow \($\), the two may be able to able to save on their borrowing costs. That could happen if each borrows in the market in which they have a comparative advantage and then swapping into their preferred currencies for their liabilities.

Assume that USD 5,000 at a fixed rate of 3% is being received in exchange for 4,000 Euros at a fixed rate of 2.5%. Payments are exchanged every year for three years, and interest rates are annually compounded.

There are two legs present in this example, a USD leg and a EURO leg.

Interest for the USD leg \(= 0.03 × 5,000 = 150\).

Interest for the Euro leg \(= 0.025 × 4,000 = 100\).

$$\begin{array}{l|c|c} \textbf{Time} & \textbf{USD} & \textbf{Euro} \\ \textbf{(years)} & \textbf{Cash flow} & \textbf{Euro Cash flow} \\ \hline 0 & -5,000 & +4,000 \\ 1 & +150 & -100 \\ 2 & +150 & -100 \\ 3 & +150 & -100 \end{array}$$

Assume that a year after the first exchange occurs, the risk-free rate for all maturities in USD is 4.5% and 3.5% in Euros. Assume also that 1 Euro = 1.15 USD.

To value this swap, we follow the below steps;

$$\begin{align*} \text{Value in USD} &= 150(1.045^{-1})+150(1.045^{-2}+150(1.045^{-3}) = 412.3447\\ \text{Value in Euros}& = 100(1.035^{-1})+100(1.035^{-2}+100(1.035^{-3}) = 280.1637\\ \end{align*} $$

The value of the swap in USD is therefore:

$$ \text{Value of the Swap} = 412.3447 – 280.1637×1.15 = 90.156445 $$

Other common types of currency swaps include:

These two currency swaps are valued by valuing each leg in their respective currencies. In valuing the floating rate, we assume that the forward rate will be realized.

In an equity swap, one of the parties commits to making payments reflecting the return on a stock, portfolio, or stock index. In turn, the counterparty commits themselves to make payments based on either a floating rate or a fixed rate.

A swaption gives the holder the right to enter into an interest rate swap. It’s purchased for a premium whose value is determined by the strike rate specified in the swaption. Swaptions can either be American or European

A floating (or market or spot) price based on an underlying commodity is traded for a fixed price over a specified period.

Historical volatility observed over a certain period of time is applied to the notional principal in exchange for pre-determined fixed volatility applied on the same notional principal.

This insures against default by a company or bond. Similar to a car insurance contract, the buyer of the protection pays the seller fixed payments over a specified period. In case there is no default, the seller does not pay anything and simply receives the protection fixed payments. In case of default, the seller then pays the buyer the notional amount.

Swaps can give rise to credit risk, especially when no collateral has been posted. The initial pricing of a transaction should, therefore, consider expected credit losses by each party. Credit risk is greatly eliminated from transactions done through a central counterparty (CCP), and this is because the CCP requires both initial and variation margins to be posted. The margins can then be transferred to the affected party in case of a default.

Credit risk in swap transactions bears critical consideration. Here, we’ll summarize key aspects of credit risk exposure:

Reducing credit risks through CCPs: Interest rate swaps and index credit default swaps involving financial institutions are required to be cleared through a CCP. The involvement of the CCP necessitates that both parties involved in the transaction provide initial margin and variation margin. Such margins serve to significantly mitigate credit risks, as they provide a buffer against counterparty default.

Risks associated with CCP default: While CCPs are pivotal in reducing credit risk, they are not without associated risks. A possible default by the CCP itself poses a tangible risk, which was evaluated in detail in a previous chapter.

Bilateral clearing and Its regulations: In situations where swaps between financial institutions are not cleared through a CCP, they are cleared bilaterally. This clearing method also requires both initial and variation margins, as per regulatory requirements. These margins function similarly to those required by CCPs, thus nearly eliminating credit risk within these bilateral transactions. While variation margin represents the day-to-day changes in market value, initial margin is posted with a third-party trustee to safeguard against potential future exposure.

Unregulated collateral posting in non-financial transactions: When swaps involve a financial institution and a non-financial company, there might be no mandatory collateral requirements. Where no collateral is posted, or where transactions are partially collateralized, credit exposure can become significant. It demands careful monitoring to assess the credit risk effectively. In such scenarios, while setting the price at the beginning of these transactions, it is essential to account for the expected credit losses by both parties involved.

Netting and credit risk consideration: It is important to contextualize that credit risk is not evaluated on a transactional basis but rather in aggregate form through netting. Whether transactions are cleared through CCPs or handled bilaterally, they are netted, mitigating the credit exposure by offsetting positive and negative values against one another

Practice Question

A steel manufacturing firm recently issued a \($500 \quad million\) fixed-rate debt at 3% per annum to fund an ambitious expansion plan. The chief risk manager at the firm has advised that the firm convert this debt into a floating rate obligation by tapping into the interest rate swap market. In this regard, he has identified four other firms interested in swapping their debt from floating to a fixed rate. The table below provided the various rates at which all the five firms can borrow:

$$ \begin{array}{c|c|c} \textbf{Firm} &\textbf{ Fixed rate} \left( \% \right) &\textbf{ Floating rate} \\ {} & {} & \textbf{6-month LIBOR +} \\ \hline \text{Steel} & 5.0 & 2.5 \\ \hline \text{Firm X } & 4.5 & 1.0 \\ \hline \text{Firm Y} & 7.0 & 4.0 \\ \hline \text{Firm Z} & 6.5 & 2.5 \\ \hline \text{Firm T} & 6.0 & 3.5 \\ \end{array} $$

Identify the firm with which the manufacturer stands to yield the greatest possible combined benefit.

A. Firm T

B. Firm Y

C. Firm X

D. Firm Z

The correct answer is D.

$$ \begin{array}{c|c|c|c|c|c} \textbf{Firm}& \textbf{Fixed rate} & \textbf{Floating rate} & \textbf{Fixed spread} & \textbf{Floating} & \textbf{Possible} \\ {} & {} & \textbf{LIBOR +} & {} & \textbf{spread} & \textbf{benefit} \\ \hline \text{Steel} & 5.0 & 2.5 & {} & {} & {} \\ \hline \text{Firm X} & 4.5 & 1.0 & -0.5 & -1.5 & 1.0 \\ \hline \text{Firm Y} & 7.0 & 4.0 & 2.0 & 1.5 & 0.5 \\ \hline \text{Firm Z} & 6.5 & 2.5 & 1.5 & 0.0 & 1.5 \\ \hline \text{Firm T} & 6.0 & 3.5 & 1.0 & 1.0 & 0.0 \\ \end{array} $$

The net borrowing savings by entering into a swap is the difference between the spreads, i.e., \(\Delta \text{fixed} -\Delta \text{floating}\).

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.