Derivatives

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Define derivatives and explain... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

Cross-product netting, often known simply as netting, refers to a process where cashflows are offset and combined into a single net amount. Netting occurs when a set of bilateral contracts have both positive and negative values.

Following a default event, a counterparty cannot demand payments on positive value contracts while stopping payments on negative value contracts. Netting reduces the exposure to the net value for all the contracts covered by the netting agreement. It is an effective way of preventing “cherry-picking” by the administrator of the defaulted counterparty.

Close-out is the immediate cancellation of all contracts with the counterparty that has defaulted. At the point of default, all the remaining contractual obligations are terminated, and the final positive or negative positions are combined into a single net payable or receivable. The result is an immediate realization of net gains or losses.

The over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives market is fast-moving, with participants taking multiple positions regularly. A single derivative portfolio can have a large number of transactions. Considering that all these transactions involve the exchange of cash flows and may require the posting of collateral, netting can help simplify the transactions into a single payment where possible.

A single counterparty can have hundreds or even thousands of separate derivatives transactions with a party. In the event of default, such a party would make a huge loss. For that reason, it is important to have a mechanism that can quickly terminate such transactions and replace (re-hedge) their position.

The ISDA Master Agreement is the standard document that sets out the provisions that govern the OTC derivatives market. It was developed by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). There have been several versions of the Master Agreement, driven by the need to update the guidelines to take emerging issues into account.

While developing the provisions, the ISDA consults and works closely with industry experts from around the globe. This is informed by the need to harmonize the application and enforceability of the provisions, particularly with regard to key issues such as netting and close-out. However, differences still persist. In some jurisdictions, for example, netting is not enforceable in a default scenario.

The ISDA Master Agreement is divided into two sections:

In a summary, therefore, the ISDA Master Agreement serves the following purposes:

Netting takes two forms: payment netting and close-out netting.

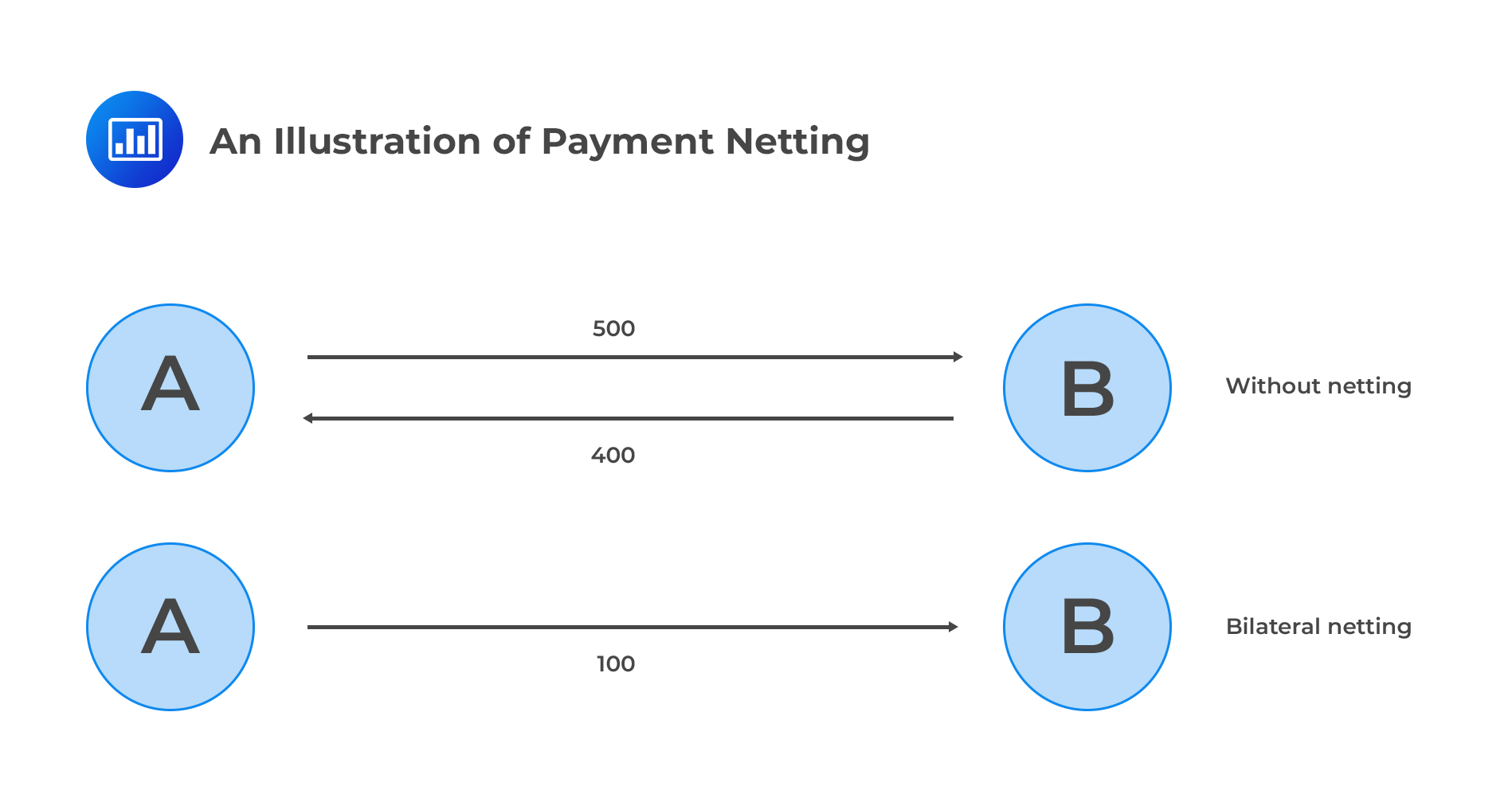

Payment netting involves the netting of payments between two counterparties in the same currency and in respect of the same transaction. The goal of payment netting is to reduce settlement risk (it is sometimes referred to as settlement netting).

On a given day, counterparties may be mandated to exchange multiple cashflows. Underpayment netting provisions allow the parties to combine all the cash flows into a single payment per currency. Let’s say Party A and Party B have engaged in an interest rate swap denominated in British pounds and at the end of the day, Party A owes Party B a fixed payment of 500 pounds, and Party B owes Party A 400 pounds. With a payment netting provision, Party A would simply pay Party B 100 pounds to settle their accounts.

Close-out Netting

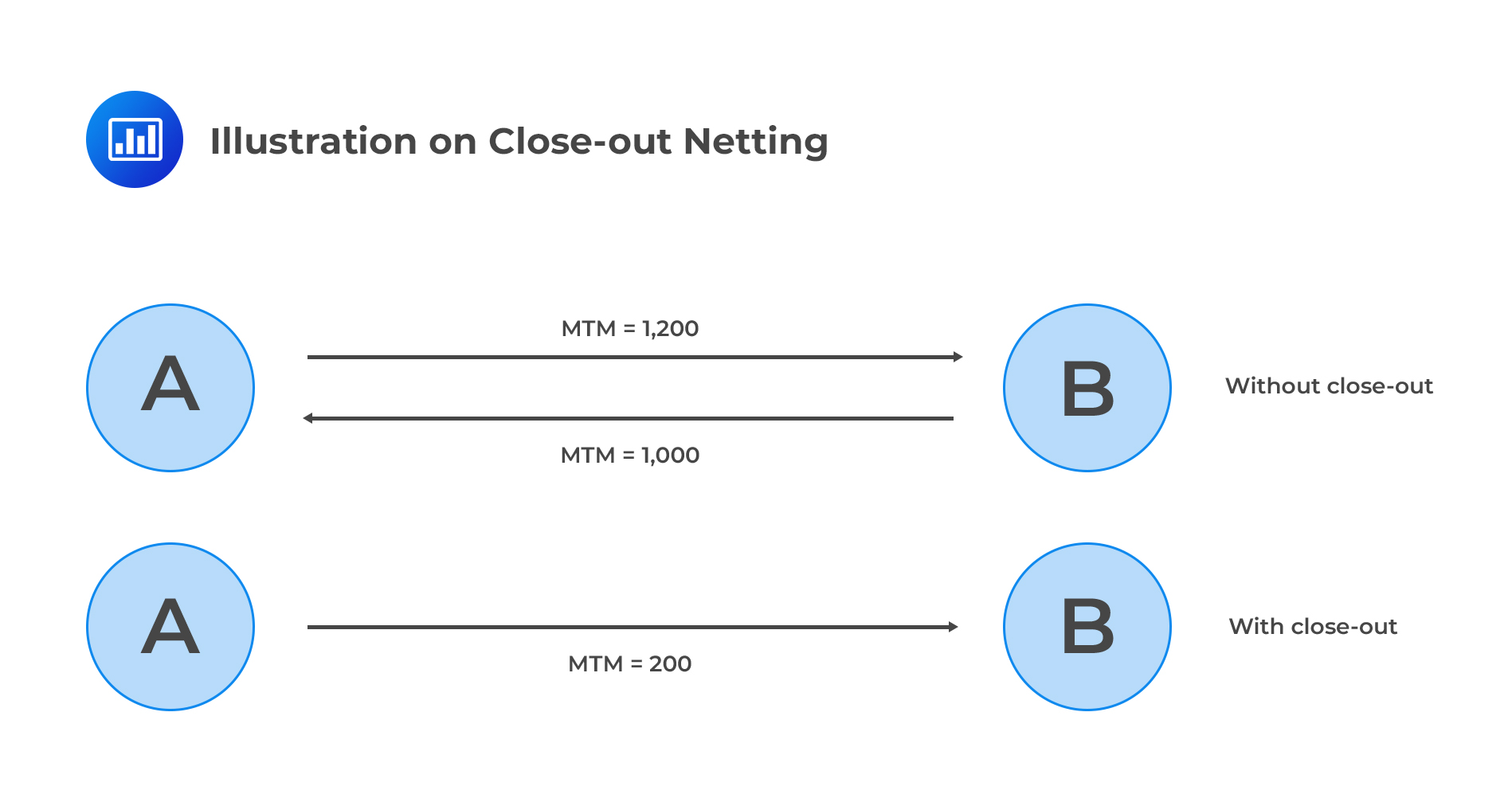

Close-out NettingClose-out is the immediate cancellation of all contracts with a counterparty after a termination event. It usually happens following a default event, and the goal is to reduce counterparty risk. Transactions between counterparties are tallied up and reduced to a single net amount that is paid by one party to the other.

Let’s go back to our example above involving parties A and B. This time, however, let’s assume that there are hundreds of transactions between them. Assume that Party A can’t fulfill its obligations. At that point, all outstanding contracts are terminated, and the final replacement values of Party A’s positions are marked to market and amalgamated into a single net payable or receivable. Party A makes this payment to Party B (or receives an amount from Party B, should Party A actually come out ahead).

If the contract between Party A and Party B does not allow close-out netting, then Party B would have to join the ranks of other Party A’s creditors. In such circumstances, reimbursement might take years and result in a smaller amount since proceedings usually drag in court, and a final verdict can be subjected to multiple appeals.

In the event of the default of Party A, without netting, Party B would need to pay 1,000 pounds to Party A and would not receive the full amount of 1,200 pounds owed. With netting, Party B would simply receive 200 pounds from Party A and suffer no loss.

In the event of the default of Party A, without netting, Party B would need to pay 1,000 pounds to Party A and would not receive the full amount of 1,200 pounds owed. With netting, Party B would simply receive 200 pounds from Party A and suffer no loss.

By reducing multiple exposures into a single net amount, netting reduces risk and improves the operational efficiency in OTC markets. On the downside, however, netted exposures can be volatile and frequently move from positive to negative, something that can make it difficult to control exposure.

It introduces discipline into the OTC market settlement process and achieves transparency of payment flows

A party may wish to exit a rather illiquid trade with one counterparty so as to eliminate market risk. Alternatively, the party could enter an offsetting position with another counterparty, but this would bring in operational risk and counterparty risk. In addition, the party can take advantage of netting and execute a reverse trade with the initial counterparty, removing both market and counterparty risk. On the downside, however, the initial counterparty may not offer favorable terms for the offsetting transaction when it’s clear that the other party “wants out.”

An entity can reduce counterparty risk by executing multiple trades with a single counterparty (which possibly has a proven track record), rather than holding many positions with different counterparties. A single counterparty would also make it possible to extract more favorable trade terms, particularly on matters collateral.

If trading rules didn’t allow for netting, counterparties in financial distress would barely do business. That’s because their counterparties would feel inclined to cease trading and terminate all at-risk contracts immediately the distress becomes evident, throwing the distressed counterparty deeper into financial trouble. With netting, the risk of losing out on multiple contracts is significantly reduced and the financially healthy counterparty can trade assured that the total multi-contract exposure will be reduced to a net single amount.

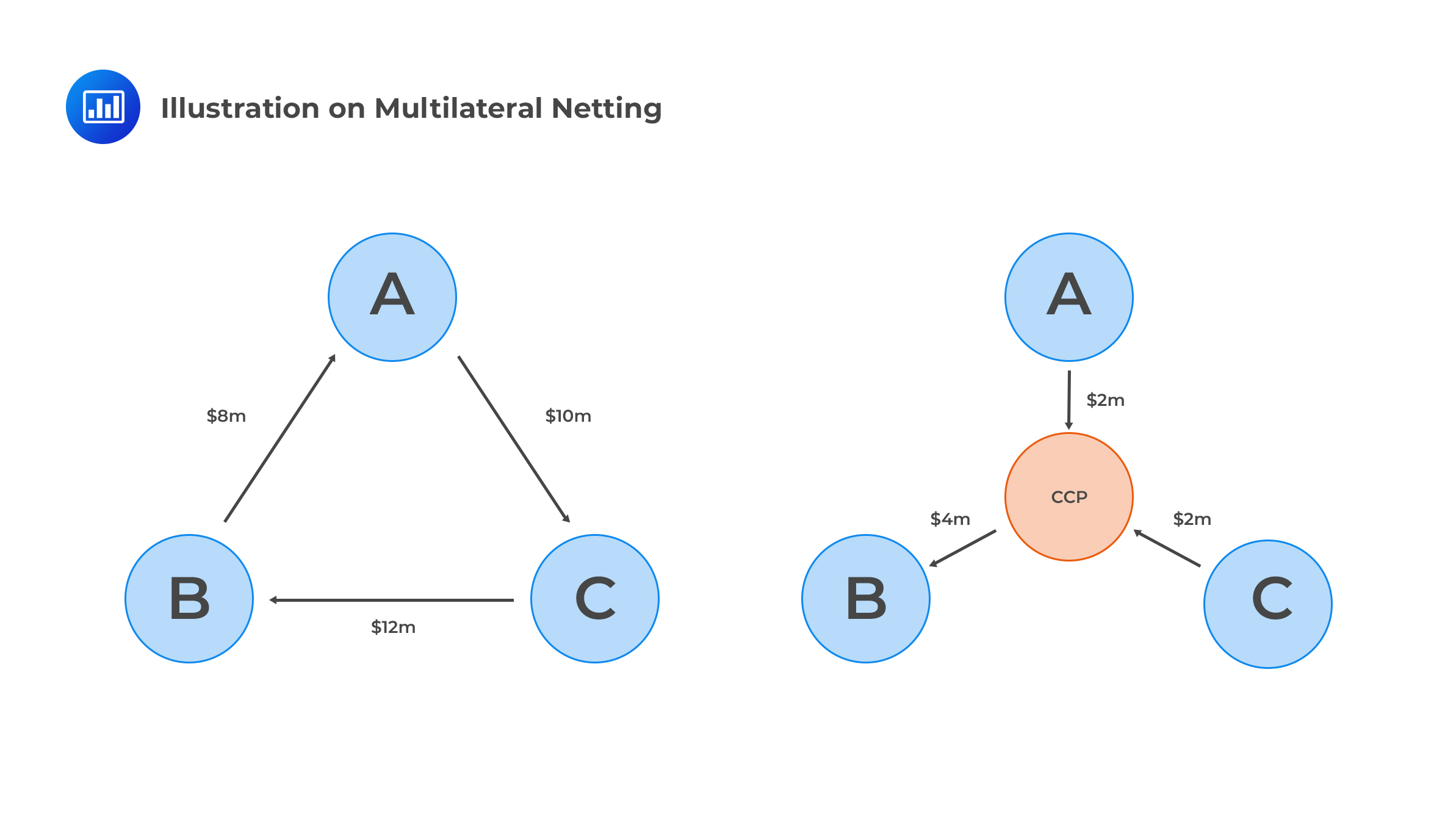

Up to this point, we have looked at netting under the rather convenient assumption that there are only two parties, and netting arrangements are bilateral. In reality, however, a single counterparty gets into tens or even hundreds of trades with different counterparties. Given four parties, A, B, C, and D, for example, A can have an exposure to B, B may have an exposure to C, and C may have an exposure to A and D. If any one of these entities defaults, the settlement, and termination process would be much more complicated than in the bilateral scenario.

Multilateral netting works quite seamlessly when a central counterparty (CCP) is involved. The CCP serves as an intermediary between trading entities, effectively acting as the counterparty to buyers and sellers. The CCP guarantees the terms of the trade even if one of the counterparties defaults. In other words, it is the CCP that bears the lion’s share of the total counterparty risk. The obvious disadvantage of his arrangement is that it results in less incentive for the counterparties to monitor each other’s credit quality. Multilateral netting also requires trading disclosure; all entities must disclose all their positions. Further, all entities have to channel transactions through the central counterparty. That way, it is very difficult to keep proprietary information confidential.

Acceleration Clause

Acceleration ClauseBesides close-out, some OTC contracts contain an acceleration clause, which permits a creditor to accelerate (make immediately due) future payments if a predefined event such as default or rating downgrade occurs. Rather than an acceleration, close-out is the termination of all contracts between the solvent and insolvent counterparty. Termination implies that all contracts are canceled and a compensation claim immediately launched based on the cost of replacing the contract on identical terms with another counterparty.

For a netting clause to be useful in a derivatives contract, there must be some chance that an instrument will have a negative MTM at some point in its lifetime. If the instrument can only have positive values, it can never have a beneficial impact on the overall exposure. A good example of such instruments would be long option positions where the premium is paid upfront (at the onset of a contract). These include swaptions, FX options, and equity options. Other instruments do have a chance of having a negative MTM, but it can be extremely low. These include long option positions without an upfront premium, receiver interest rate swaps with a downwards sloping yield curve, and payer interest rate swaps with an upward sloping yield curve.

Even if all trades with a given counterparty can only have positive values, there are several reasons an institution would still put them under a netting agreement:

Termination provisions allow a party, say a bank, to terminate (bring an end) a trade if (I) there’s evidence that the counterparty is on the brink of bankruptcy, or (II) if there happens to be a breach of contract by the counterparty, for instance, by defaulting on payments.

The current exposure of a long-dated derivative position can be relatively small and manageable. As time goes by, however, the exposure can increase significantly to unmanageable levels, increasing the probability that the counterparty will not honor their obligations. Termination provisions help to reduce exposure in such circumstances.

Termination provisions take the form of a walkaway feature of a reset agreement.

A walkaway feature is a clause that effectively allows an institution to cancel transactions in the event that the counterparty defaults. Institutions would have an incentive to take this route only if they are in debted to the counterparty. While the walkaway feature does not reduce credit exposure, it allows the surviving party to cut short all payments and allows them not to settle any amounts owed to the counterparty. Walkaway clauses were quite common prior to the 1992 ISDA agreement but have since been removed from the standardized ISDA documentation. Walkaway features do not mitigate counterparty risk per se, but they do result in potential gains that offset the risk of potential losses.

A reset agreement is a clause that prevents a transaction from becoming strongly in-the-money (to either party). It does this by adjusting product-specific parameters that reset the transaction to be more at-the-money. Sometimes the reset coincides with payment dates specified in the contract. Other times, a reset may be activated following a breach of some market value.

In a cross-currency swap, for example, the MTM on the swap is exchanged at each reset time in cash. In addition, the FX rate is reset (typically) to the prevailing spot rate. The reset implies that the notional on one leg of the swap will change. The reset works pretty much like closing out the transaction and executing a replacement transaction at market rates. It consequently reduces the exposure.

Additional termination events are events whose occurrence allows a party to terminate OTC derivative transactions if the creditworthiness of their counterparty declines to the point of bankruptcy. A commonly quoted ATE in derivative contracts is a rating downgrade of one or both counterparties. For parties that are usually not rated, such as hedge funds, metrics such as market capitalization, net asset value, or key man departure may be used.

ATEs can be particularly useful when the counterparty has relatively good credit quality. They may also be useful for long-dated transactions as the creditworthiness may change at some point in the future, however “rosy” the current financial standing is.

ATEs may be mandatory, optional, or trigger-based, and may apply to one or both parties in a transaction.

In recent years, ATEs have been found to have potential dangers because of two main reasons:

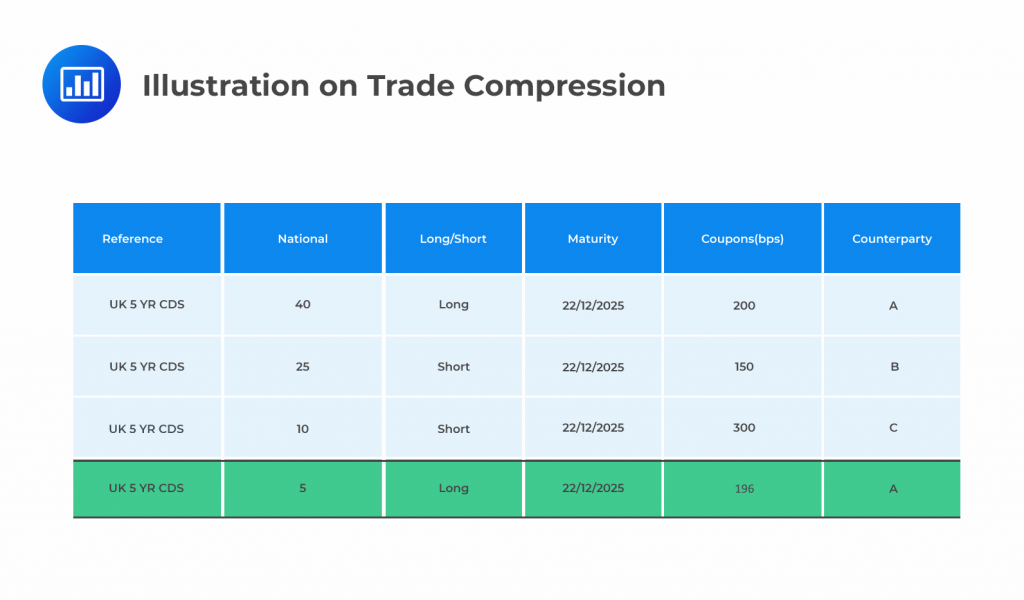

As we saw earlier, multilateral netting works in the presence of an intermediary (such as an exchange or CCP), and it also tends to mutualize and homogenize counterparty risk, reducing the motivation for parties to monitor the credit quality of the party on the other side of a trade. Trade compression presents an attempt to achieve multilateral netting without involving an intermediary.

By definition, portfolio compression is a risk reduction technique where two or more counterparties terminate some or all of their derivative contracts and replace them with a single derivative contract whose market risk is the same as the combined notional value of all of the terminated derivatives.

For example, assume that a party has three contracts on UK sovereign debt, all maturing in 5 years, but transacted with different counterparties – A, B, and C. It would be worthwhile to “compress” the three into a net contract, which represents the total notional value of the long and short positions. This may naturally be with counterparty A as a reduction of the initial transaction. The coupon of the new contract is taken to be the weighted average of the three original ones.

Several entities currently offer trade compression services mostly covering major OTC derivatives such as credit default swaps, interest rate swaps, and energy swaps. A good example would be TriOptima. Compression has enabled institutions to reduce credit exposures considerably.

Several entities currently offer trade compression services mostly covering major OTC derivatives such as credit default swaps, interest rate swaps, and energy swaps. A good example would be TriOptima. Compression has enabled institutions to reduce credit exposures considerably.

Question

Over the past year, Matrix Bank has entered into several interest rate swap contracts all with Delta Corp as the reference entity. To manage counterparty risk, they decide to undergo trade compression. Before the compression exercise, Matrix Bank had entered into five contracts where they received fixed and paid variable rates with a notional of $10 million each. Simultaneously, they had three contracts where they paid fixed and received variable rates with a notional of $15 million each. After the compression exercise, all contracts were combined into fewer contracts, without altering the overall economic exposure.

The risk manager at Matrix Bank is now evaluating the net notional exposure amount and identifying the party holding the net contract position after trade compression.

Based on the information, which of the following correctly states the net notional exposure amount and the party holding the net contract position?

A. Net notional exposure amount is $5 million; Matrix Bank is receiving fixed.

B. Net notional exposure amount is $15 million; Matrix Bank is receiving fixed.

C. Net notional exposure amount is $15 million; Matrix Bank is paying fixed.

D. Net notional exposure amount is $5 million; Matrix Bank is paying fixed.

Solution

The correct answer is A.

The total notional for contracts where Matrix Bank receives fixed and pays variable is $10 million x 5 = $50 million. For contracts where Matrix Bank pays fixed and receives variable, the total notional is $15 million x 3 = $45 million. Therefore, the net notional exposure after compression is $50 million – $45 million = $5 million. Matrix Bank is net receiving fixed for this amount.

B is incorrect because while the calculations correctly suggest that Matrix Bank is receiving fixed, the net notional exposure amount is overestimated. The correct net notional exposure is $5 million, not $15 million.

C is incorrect primarily because it incorrectly identifies the position of Matrix Bank. The bank is receiving fixed, not paying. The notional amount is also correctly calculated as $15 million, but the position is wrong.

D is incorrect due to the wrong position attributed to Matrix Bank. While the notional exposure is correctly identified as $5 million, Matrix Bank is receiving fixed, not paying.

Things to Remember

- Trade compression consolidates multiple over-the-counter (OTC) derivative contracts into fewer contracts, reducing operational and counterparty risks without altering the overall economic exposure.

- Compression benefits include reduced operational costs, streamlined portfolio management, and improved regulatory capital efficiency.

- It’s important to distinguish between gross notional and net notional. While gross notional indicates the total volume of trades, net notional focuses on the net exposure, reflecting the true risk position.

- Interest rate swaps often involve exchanging fixed for variable interest payments; the net position indicates the party’s net obligation or receipt.

- Periodically assessing the net notional exposure aids in effective risk management, especially in a dynamic trading environment.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.