Operational and Integrated Risk Manage ...

Introduction to Operational Risk and Resilience Risk Governance Risk Identification Risk Measurement and... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

With the increase in frequency, severity, and complexity of cyber-incidence, many legislative, regulatory, and supervisory bodies were formed. For instance, the G7 came up with Fundamental Elements of Cyber Security for the financial sector in October 2016. In the European Union (EU), the European Commission (EC) developed the Fintech Action Plan, which championed the convergence of ICT risk among supervisory authorities.

The Basel Committee on Baking Supervisory (BCBS) developed the Operational Resilience Working Group (ORG) to address cyber risk in coordination with other international bodies. The Committee mandated ORG to assess the observed cyber-resilience practices at authorities and many other firms.

The primary objective of this chapter is to identify, describe and compare different types of regulatory and supervisory cyber-resilience practices across different jurisdictions based on the input of the Operational Resilience Working Group (ORG) to the FSB survey in April 2017. This report was publicly issued in October 2017. The report contained cybersecurity regulations, guidance, and supervisory practices at both national and international levels.

The Basel Committee on Baking Supervisory (BCBS) uses the definition of cyber resilience by the FS Lexicon as “the ability of an entity to continue to execute its purpose by anticipating and adapting to cyber threats and other appropriate variations in the environment and enduring, containing, and rapidly recovering from the cyber-attacks occurrence.”

Cyber resilience expectations in many jurisdictions are based on quality and IT risk guidelines. These guidelines are outlined in various regulatory standards that communicate a jurisdiction’s expectations and promote good practice. The guidelines touch on governance, IT recovery and management, information security, IT recovery, and IT outsourcing structures management. Cyber risk management is a branch of operational or IT risk guidance.

Appropriate cyber risk management guidelines are based on information security. Sizeable jurisdictions have issued appropriate guidance concerning information security. For instance:

In areas where specific cybersecurity regulations are absent, the supervisors encourage the regulated organizations to implement the international standard and use prescribed guidance and supervisory practices according to national cyber agencies’ hierarchical initiatives. Some of the primary international standards are NIST and ISO/IEC.

Some Jurisdictions, however, develop standards that the financial sector must enforce. For instance, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is a prudential standard to ensure that the APRA-regulated organizations take measures to be cyber-resilient. Such organizations maintain information security and follow up information security vulnerabilities and threats.

Most regulators have instituted guidance or regulations with different levels of maturity. These regulations generally touch on enterprise IT risk management. Nevertheless, the regulations do not include specific regwulations or supervisory practices that address cyber-risk management of essential business functions, interconnectedness, or third-party management. In addressing this challenge, supervisory expectations and practices were identified and analyzed in each of the following, appropriate to governance:

Most of the regulators do not require organizations to develop a cyber-security strategy. However, organizations are expected to have a board-approved information security strategy, policy, and procedures based on the rule of effective oversight of technology. For instance, most European jurisdictions require that the cyber risk strategy be addressed by the organization-wide risk management framework and information security setting, which is monitored and reviewed by senior executives.

Jurisdictions institute cyber-security strategy requirements through three types of non-mutually regulatory types:

A sizeable number of jurisdictions have issued guidance and requirements on the board of directors’ roles and responsibilities (BoD) and senior management. Some prioritize the BoD and senior management in overseeing the business technology risks. However, other jurisdictions regard cyber-governance as a risk that must be addressed in the existing risk management structures.

However, a significant number of jurisdictions recognize the importance of the roles and responsibilities of the BoD and senior management in cyber governance and controls. For instance, in the US, EU, and Japan, some guidelines encourage G-SIBs and D-SIBs to enforce a well-defined and risk-sensitive management framework based on the initiatives of the BoD. Moreover, the upcoming market implements a more granular and prescriptive cyber-security arrangement.

Most regulators have adopted the 3LD (Three lines of defense) risk management model to monitor the cyber-security risk and controls. The banks must define the responsibilities without leaving any gaps for those who do not require the implementation of the 3LD model.

Therefore, the degree of 3LD implementation significantly varies. Thus, the first and second defense line is emphasized more than the third line of defense in almost all jurisdictions. This draws back the use of the 3LD model.

In order to maintain cyber-resilience in an organization, the staff of an individual bank should be aware of the cyber risk and the existing risk culture. Most regulators in different jurisdictions have laid down the importance of risk awareness and risk culture for staff and management hierarchies such as BoD and employees.

Regulatory requirements include increasing cybersecurity awareness and other staff-related issues in regulated entities. In other jurisdictions, regulators require incorporation of cyber training in all phases of employment, from recruitment to the termination. Employers may require non-disclosure clauses within the staff agreements during training sessions. Moreover, some jurisdictions may require employees to verify their credentials at regular intervals to avoid insider threats.

In some jurisdictions, regulators determine whether banks have effective processes and controls that ensure that employees, contractors, and third-party dealers understand their roles and responsibilities to reduce the risk of theft, fraud, or misuse of the institution’s facilities.

Most of the regulators advocate for the establishment of common risk culture to ensure effective cyber-risk management.

A small number of jurisdictions highlight the controls and supervisory guidance on the cyber-security architecture. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, cybersecurity architecture is based solely on periodical self-assessment.

The characteristics, such as skills and competencies, regulatory framework, and other practices, differ across jurisdictions. Some jurisdictions have unique IT standards that cover the IT workforce’s responsibilities and the information security functions specifically towards the cybersecurity workforce and training. The standards touch on the assessment of the team division staff expertise, the training procedures, funding, and resource allocation to a firm’s cybersecurity.

Many regulators check the cybersecurity workforce through on-site inspections, where they interact with the relevant specialist by word of mouth or by self-assessment questionnaire. The regulators also check the training sessions.

Generally, there exists a wide range of practices and regulatory expectations surrounding the cybersecurity workforce. As such, there are no jurisdictions that have formulated any regulatory expectations. In other jurisdictions, the regulatory requirements are limited to supervisory goals. Therefore, there may be no workforce skill and training assessment by the cyber-security supervisors. Nevertheless, countries such as Singapore and the UK have issued designated frameworks to certify cyber workforce skills and competencies.

The approaches used to assess cyber-resilience vary across jurisdictions. However, most of the assessment focuses on cyber risk in the context of the scale, complexity, business model, and previous findings. Afterward, the organizations are categorized depending on the supervisory initiatives. A supervision program is chosen while concentrating on financial and operational matters using the existing international and national legislation.

Some jurisdictions, such as the EU, have specific guidance on when cyber-security review is necessary. Such practices include an organization’s assessment, results from on-site inspections or questionnaires, and incidents.

Many jurisdiction conduct both on-site and off-site reviews and inspections of regulated organizations’ information security control. These review assess organizations’ compliance with the regulatory standards. These assessments are either done as a form of general technology or risk assessment. The assessments tend to concentrate on governance and strategy, management and frameworks, controls, third-party arrangement, training, monitoring and detection, response and recovery, and information-sharing and communication.

The industry’s engagement aims to influence its behavior or get feedback and views on the regulatory work. Industry engagement can be done using conferences and other methods, ensuring the outreach of regulated entities and industry participants. Some jurisdictions incorporate third-party service providers in the engagement through events with regulators, supervisors, industry, and third-party services.

Most jurisdictions acknowledge the significance of mapping and classifying business services and supporting assets to strengthen resilience. Moreover, independent assurance provides management and regulations with an evolution of whether appropriate controls have been instituted effectively.

Cyber-security controls are executed via risk-based decisions against a regulated institution’s risk appetite. Conventionally, the regulated entities test information security controls applied to hardware, software, and data to prevent, detect, respond, and recover from cyber-attacks.

On the other hand, the supervisors review and challenge the regulated organizations’ methods in testing the controls and the remediation of the issues identified. This includes reviewing the survey response, threat and vulnerability analysis, risk analysis and audit report, and control testing reports such as penetration testing and health checks.

Some jurisdictions that have developed standardized penetration tests are the ECB, the Netherlands, and the UK. The tests are voluntary and funded by regulated organizations and are mostly aimed at more significant and more systematic institutions. Most regulated tests target a regulated organization’s protective and detective cyber-resilience, while others focus on the response and recovery abilities.

Establishing precise cyber-risk controls is as essential in building effective cyber resilience as reviewing these controls. Some jurisdictions utilize the taxonomies of controls to determine whether there are gaps in their supervisory approach coverage. However, the taxonomies differ in jurisdictions and are independent of harmonized concepts and definitions.

Evaluation of service continuity concentrates on checking whether the risk management frameworks, business continuity management strategies, IT disaster recovery arrangement and data strategies work in the same direction.

Many jurisdictions require the institutions to develop a framework or prevention policy, detection, response, recovery arrangement, and reporting threats. For instance, there is an incident management guideline in the US. It entails identification of the source of the compromise, analysis and classification of events, and escalation and reporting of the incident.

The analysis of a regulated organization’s incident response and recovery plans concentrates on the initiated plans, implementation of the plans, and preservation of the data in specific actions to crucial technology.

Some jurisdictions, such as Australia and Belgium, conduct a post-incident study by discussing the regulated entity’s response. Besides, they analyze an incident’s root cause.

Apart from testing, most supervisors and banks conduct training exercises and practices to prepare for responding to an incident. After the joint exercise, a summary is published to enable others to learn.

A proportion of the jurisdictions have developed methods to analyze or benchmark a regulated institution’s cyber-security and resilience. The jurisdictions herein concentrate on reported incidents, surveys, penetration tests, and on-site inspections. These metrics are non-comparable to standardized quantitative metrics for financial risk and resilience. However, they act as indicators that provide information on the regulated entities’ approach to establishing and ensuring cybersecurity and resilience.

Moreover, the supervisory authorities can depend on the regulated entities’ management information, which can differ from one entity to another.

Conventionally, the regulators and the regulated institutions in different jurisdictions use retrospective (backward-looking) indicators to determine a technology function’s performance. These indicators are usually presented to the Board of Directors and executives as part of management information that regulators may analyze.

The use of retrospective indicators is suitable for entities operating in a relatively stable risk environment over time and significantly independent from external impacts. However, due to the dynamism of cyber risk, it changes an entity’s response and protective changes. Despite the popularity of backward-looking indicators, jurisdictions are increasingly embracing forward-looking indicators as direct and indirect metrics of reliance. The forward-looking indicators show whether an entity is likely to be more or less resilient in the event of a risk threat.

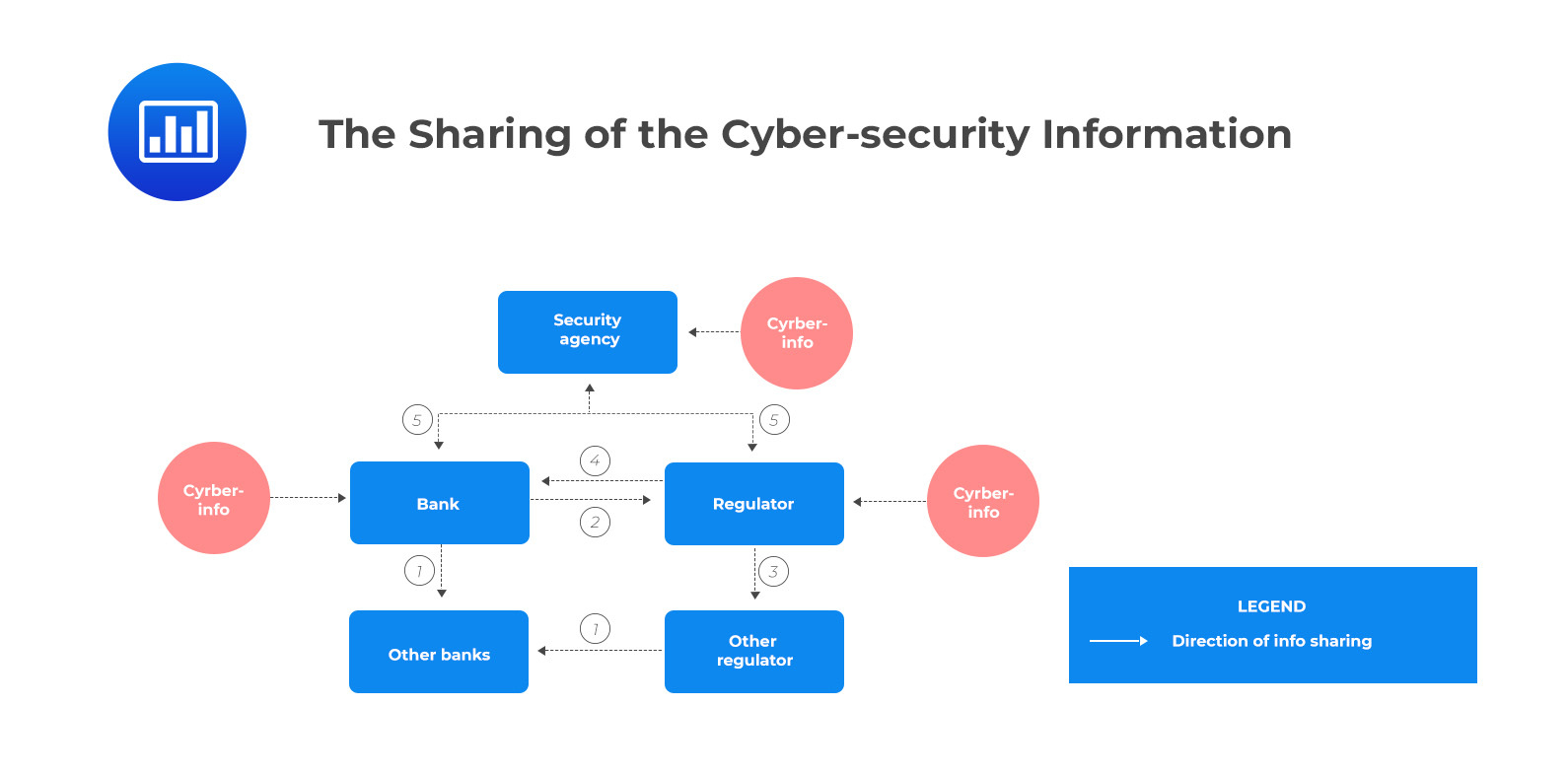

The Basel Committee has established a mandatory or voluntary mechanism of sharing information to promote the sharing of cyber-security information among banks, regulators, and security agencies, as shown in the diagram below:

There are five types of information sharing: sharing among the banks, sharing among the banks and regulators, sharing among the regulators, sharing from regulators to banks, and sharing security agencies.

Sharing among the regulator is least observed because of the less regular features of the regulators’ information-sharing arrangement. It usually happens on an ad hoc basis at a bilateral level or within the supervisory colleges under certain instances.

The information regulators and banks share may include information on cyber threats, cyber-security incidents, regulatory and supervisory responses in case of cyber-security incidents, and cyber threat identification. Among this information shared, information on cybersecurity incidents is broadly observed in sharing between the banks and regulators, and security agencies. Moreover, cyber threat information is broadly shared among banks.

Some jurisdictions have established guidelines on sharing cybersecurity information for more effective sharing by banks and regulators. However, in jurisdictions with observed information sharing among the banks, there is less observation of information sharing from the banks’ regulators due to the current sharing model among the banks. Hence, there is no need to share information. Simultaneously, in jurisdictions with an effective mechanism of information sharing among the banks to regulators, there is less information sharing with the security agencies due to the assignment of responsibilities for cybersecurity information processing among regulators and security agencies in a given jurisdiction.

Banks share information such as cybersecurity threats with peer banks through approved channels so that peer banks can respond on time in case of a similar threat. The regulators are not directly involved in bank-to-bank information sharing. However, they have a role in establishing voluntary sharing mechanism approaches for cyber vulnerability, threat, and incident information and may indicate imminent threats.

A proportion of the jurisdictions have developed a public sector platform for information sharing, while others encourage the private sector establishment of information-sharing organizations. For instance, Brazil, Japan, and Saudi Arabia require banks to share information among the banks through regulations and mandates. Moreover, some jurisdictions have established public or private forums or government-established centers for information sharing.

The extent of the information sharing and collaboration among the banks depends on the financial industry’s culture and the level of trust among the banks.

The information shared from the banks to regulators is limited to cyber-incidents following regulatory reporting regulations. The bank-regulator information sharing is essential because:

Different authorities develop the reporting requirements for different reasons depending on the mandate, such as consumer protection. In almost all jurisdictions, reporting cyber incidents to regulators is mandatory, with different levels of requirements and applications. For instance, all the European Union’s regulated entities must report the cyber incident to the competent authorities.

The scopes and perimeters of reporting depend on the type of authority (such as national security) and their mandate (such as banking supervision), the sectors involved, and the geographical range (such as national level). While some supervisors concentrate on the already occurred incidents, some require continuous monitoring and tracking of the potential cyber-threat because many institutions might delay reporting the incidents since they want to protect their reputation.

The reporting frameworks differ, ranging from formal to informal communications, such as verbal updates and emails. Therefore, reporting differs in the following aspects:

The factors above reflect the difference between banks in different jurisdictions or supervision. That is, the banks are required to fill in various types of templates with different taxonomy, reporting timeframe, and threshold.

Under information sharing, the direction of the information is always from the banks to the regulators. However, this can be changed when the regulators want to warn the entities against incoming threats.

The regulators share information domestically or internationally based on relevant mandatory or voluntary information-sharing structures. Some of the information regulators share include regulatory actions, responses, and measures.

Regulators’ information sharing is least observed across jurisdictions (except some ad hoc communication channels). However, information sharing among regulators is highly encouraged due to increasing cyber fraud across jurisdictions. The regulator-regulator information sharing can facilitate timely guidance to protect the banks from these fraud schemes.

Information flows from the regulators to the banks through appropriate channels, depending on the regulator’s information from banks and other sources. Some jurisdictions, such as China and Turkey, have developed defined standards and practices that govern information sharing between regulators and banks. Information flows from banks to the regulators in the these jurisdictions. The regulators then analyze the risks to the financial industry, after which they share the information the banks as required based on the risk analysis. However, when the information contains customer-specific information, the regulator shares anonymized information.

The regulators with an established regulator-bank mechanism publicly share the information through informal channels such as sharing platforms and meetings. However, when the regulator has non-public information, then the information is shared with appropriate participants through informal means. The confidentiality and anonymity of the affected organizations are maintained. Hence, the confidence and trust of the regulators are also maintained.

Some jurisdictions (such as China) have made it mandatory for regulators to share information with banks. However, others such as Singapore support voluntary information sharing by regulators.

Information sharing with security agencies involves sharing information between banks or regulators with security agencies in a particular jurisdiction. Information sharing with the security agencies is crucial in creating awareness of cyber threats in a timely way and improving the defense measures against attackers.

In jurisdictions with established security agencies, the said agencies serve as the cyber threat notification focal points. Therefore, jurisdictions have established the standards and practices of crucial entities and regulators to share cyber-security information with national security agencies. Some jurisdictions (such as the UK) support voluntary reporting, while others (such as Canada and France) require mandatory information sharing.

There is no full assurance that the cyber resilience of an entity will serve it purposefully. The regulators experience this drawback concerning financial institutions and financial institutions concerning third-party service providers. Excessive use of third-party providers proves to be a challenge to both jurisdictions and regulated entities to have a clear view of the established controls and the level of the risk.

Third parties are taken as follows to establish a clear understanding of the practices associated with cyber-resilience:

The link between cyber resilience and third parties discussed in the following lines:

There exist regulations in different jurisdictions that mandate an institutions to come up with management and board-approved outsourcing (or organizational) frameworks that outline the following:

Regulators may also require the institutions to enforce a contractual framework, where they should define the generic rights, obligations, roles, and responsibilities of the institution and the service provider.

The standard practices regarding third parties include:

A portion of international standards accepts that the institutions may, importantly, depend on third-party interconnections other than outsourcing third parties. For instance, the ISO 27031 standard states the requirements for hardware, software, telecoms, applications, third-party hosting services, utilities, and environmental issues such as air conditioning.

Some jurisdictions require financial institutions to sign a prior contract with their clients when they deliver financial services through the internet. Among others, internet finacial services may include consultation and personalized data management or accomplishing transactions.

Most jurisdictions require prior notification or approval of cloud outsourcing activities through questionnaires or templates. These documents might not be similar across jurisdictions, but they provide the documents for internal risk analysis.

The regulations and practices can be made future-proof by focusing on the products and services and new expectations for secure development and procurement. Notably, specific requirements require that the systems be designed based on security principles, bearing in mind that devices, applications, and systems will be interconnected in the future, hence vulnerabilities.

The third parties’ supervision varies across jurisdictions, but the supervisor uses conventional tools (such as self-assessment questionnaires) to meet standard expectations. Third-party providers can be checked using on-site reviews and inspections based on the formal requirement or authority or cooperation from service providers. In some cases, the supervisors can work directly with the cloud providers – both formally and informally – to incorporate the right to audit in the contracts for the financial industry or participate in the regulatory conferences organized by large cloud service providers.

A supervisory college model can also be established to supervise and share information concerning huge and globally active service providers such as cloud providers. Such models assist in addressing the issues that might arise due to mandate limitations and regulatory fragmentation.

For financial institutions to protect the availability and continuity of crucial business activities in cyber-attacks, the regulators authorize financial institutions to analyze the said occurrences. Essentially, this helps them design and implement appropriate plans, procedures, and technical solutions. In addition, situational analysis helps initiate adequate mitigation procedures. Moreover, for a business that depends on third-party interconnections, the regulations require that the financial institutions align the business continuity plans of crucial suppliers with their needs and policies based on continuity and security.

It is a widespread practice that the regulator requires the entities to define the recovery and resumption objectives. The targeted activities and services are usually cloud outsourcing, settlement processes, or internet services.

Plans and procedures’ expectations address tasks and responsibilities of incident management, response, and recovery in case of threats. There is need for information and communication flow between internal and external stakeholders. Such communication should address the needed resources, including planned redundancy, to promote the quick transfer of outsourced activities to a different provider if it is likely that the service provider’s continuity or quality will be impacted.

Many regulators and global standards require that financial institutions frequently test protective measures to determine if they are effective and efficient and make appropriate adjustments. Highly established regulators expect tests for crucial activities to be based on realistic and probable threats. Such tests should be conducted annually. Besides, service providers and essential counterparties should be included via collaborative and structured resilience testing. Audits and monitoring activities of the outsourcing parties then support these tests.

The similarities in the supervisory expectations and practices in terms of business continuity and availability are commonly seen in the entities’ standalone business continuity. These similarities could give an environment to extensively test continuity and resilience in a collaborative and coordinated form that involves a larger financial institution.

The supervisory requirements on the internal/external audit of the third parties are categorized into two:

Despite that, the current regulations are based on conational outsourcing and maybe cloud computing providers. The scope of requirements for rights to inspect and audit is majorly focused on the banking sector. Shared and independent audit reporting on crucial interconnections with the third parties promotes an effective and efficient audit approach.

Regarding the security expectations for outsourcing and cloud computing providers, entities must monitor if their providers are compliant. However, most regulations do not give a method to test or verify the extent of compliance by the providers. One of the viable methods might be bank-led or supervisor-led red teaming exercises aimed at interconnections.

The confidentiality and the integrity of the information are usually stated under general data protection requirements. To achieve this end, it is a requirement that contractual terms incorporate confidentiality agreement and security requirements for protecting the information of a bank and its clients. Additionally, the banks are required to maintain the cyber-resilience as per the CPMI-IOSCO guidance. The financial market infrastructure must design and tests its systems and processes to resume its critical operations within 2 hours of an attack and complete its settlement by the end of the day.

An increasing proportion of jurisdictions requires cloud service providers to ensure that the information transferred to the cloud is based on contractual clause. Further, various cloud-specific issues should be addressed to guarantee the data.

In some other jurisdictions, regulations require that outsourcing structures comply with the legal and regulatory provisions on protecting personal data, confidentiality, and intellectual property. However, this requirement varies across jurisdictions.

According to Basel Committee’s Sound Practices (in their 2018 publication), banks may need specialist competencies to determine whether their risk functions can maintain sufficient authority over the emerging risk linked to new technologies.

In the context of outsourcing and the management process, the expectation is that the appropriate personnel should have the required expertise, competencies, and qualifications to monitor the outsourced services/functions effectively and should be able to manage the associated risks beyond compliance.

Regulators require the institutions to recruit sufficient and qualified personnel to ensure the continuity in management and monitoring of outsourced services or functions even after the exit of a significant person from the entity or otherwise absent. If an entity lacks sufficient internal resources in know-how or number, the general requirements are that external technical resources (such as consultants and specialists) should be hired to complement or supplement the in-house personnel.

Similar to regulatory expectations, the supervisory practices also have commonalities in that the human resource and qualifications for managing third-party connections and relationships are executed in on-site inspections. In jurisdictions where the financial supervisors can directly assess third parties, they analyze the staff’s sufficiency and qualifications and require third parties to perform background checks.

Lastly, Certified Information Systems Security Professionals or any other institution that complies with ISO 9001 Quality Management System provides an extra assurance staff qualification to manage third-party connections.

Many jurisdictions require that the supervisory authority be informed concerning the material outsourcing contracts made by the regulated organizations. Further, such jurisdictions impose conditions such as a minimum level of visibility of the functions regulated institution outsource.

Apart from the notifications and the authorization, the regulated institutions are usually required to preserve an inventory of outsourced functions (for example, IT assets such as computer hardware and software) and periodic reports from service providers, majorly concerning the measurement of service level agreements and the relevant performance of controls. In some jurisdictions, sub-outsourcing is required to be visible for the regulated institutions to manage the associated risk.

The supervisory expectations of the concerned authorities on the visibility of third-party connections vary across jurisdictions. For instance, US authorities require suppliers’ identification, documentation, and classification to address information security issues.

Practice Question

ACME Bank is a large financial institution that is undergoing a digital transformation. As part of this process, they are leveraging third-party service providers to optimize their operations, ranging from cloud computing to trading platforms. The bank’s Board of Directors, conscious of the importance of risk management, is conducting a review of the practices related to the governance of risks connected with these third-party service providers. The Chief Risk Officer (CRO) is summoned to present on the matter.

The CRO presents the following statements to the Board:

A. “We have a comprehensive framework for third-party outsourcing that details the roles, responsibilities, and rights of both ACME Bank and the service providers. This framework also includes specific risks like vendor lock-in and security concerns such as patch management.”

B. “Our focus has primarily been on managing risks associated with traditional outsourcing. However, we have not conducted in-depth risk assessments on non-traditional third parties like power suppliers or telecommunication lines.”

C. “We have a process in place to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of our data with third parties. We rely on them to have the necessary measures, and we conduct annual audits of their security practices.”

D. “Our institution maintains a record of our third-party interconnections, but we do not have complete visibility into sub-outsourcing activities. We rely on our third-party providers to maintain the integrity of these sub-outsourced functions.”

Which of these statements made by the CRO would raise the most significant concerns about ACME Bank’s current practices in the governance of risks associated with interconnected third-party service providers?

A. Statement A

B. Statement B

C. Statement C

D. Statement D

Solution

The correct answer is B.

Statement B underscores a major lapse in ACME Bank’s risk management practices. By failing to conduct thorough risk assessments on non-traditional third parties like power suppliers or telecommunication lines, the bank exposes itself to unforeseen vulnerabilities. Given the intricate nature of cyber threats today, all third-party interactions, both traditional and non-traditional, carry inherent risks that should be rigorously assessed and routinely monitored.

A is incorrect because having a comprehensive framework for third-party outsourcing that elucidates roles, responsibilities, and particular risks is a commendable practice in risk governance. This denotes that ACME Bank is proactive in understanding and managing the risks inherent with third-party outsourcing.

C is incorrect because although placing sole reliance on third parties for security standards can be a point of concern, the statement also denotes that ACME Bank conducts yearly audits of these third parties’ security practices. This effort aids in ensuring that the security measures of these third parties are stringent and up-to-date.

D is incorrect because, while not having full visibility into sub-outsourcing activities can indeed be a point of vulnerability, the absence of visibility indicates potential unknown risk exposures. Sub-outsourcing can lead to reduced control and oversight, increased complexity in risk assessment, and potential information security issues. However, in comparison to Statement B, which directly points to an outright oversight in assessing risks for certain third-party interconnections, Statement D indicates a potential oversight but not a complete neglect.

Things to Remember

- When dealing with third-party service providers, it’s vital to consider all types of interconnections, both traditional and non-traditional. Overlooking any category can expose the organization to unforeseen vulnerabilities.

- Regularly assessing and updating risk management practices is crucial, especially in a rapidly changing digital environment.

- Sub-outsourcing, where third-party service providers subcontract parts of their service, can introduce additional complexities and risks. Knowing the end-to-end chain is critical.

- Yearly audits, while useful, are just a part of comprehensive risk management. Continuous monitoring and timely interventions can further bolster security and risk management.

- Adopting a proactive approach in understanding and managing risks related to third-party interactions can offer a competitive advantage and ensure organizational resilience.