Machine Learning and AI for Risk Manag ...

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Explain the distinctions between... Read More

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

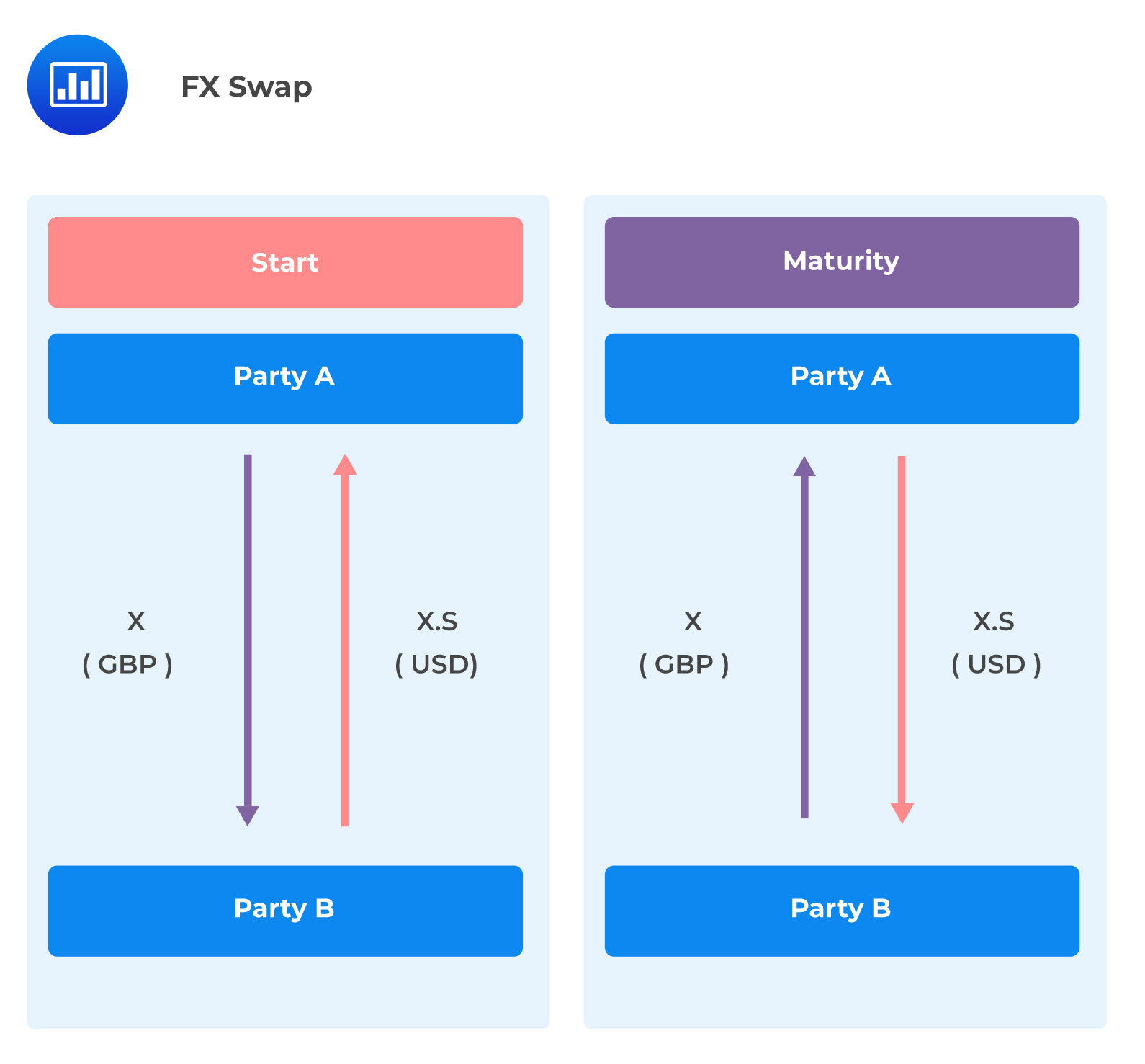

In an FX swap agreement, one party borrows one currency from another party and, at the same time, lends another currency to the same counterparty. Each party utilizes the repayment obligation as collateral. Moreover, the repayment amount is fixed at the FX forward rate as of the beginning of the contract.

In the above example, we can see that X.S at the start of the contract is the FX spot rate and X.F is the FX forward rate agreed at the initiation of the contract but exchanged at the maturity date.

In the above example, we can see that X.S at the start of the contract is the FX spot rate and X.F is the FX forward rate agreed at the initiation of the contract but exchanged at the maturity date.

FX swaps are FX risk-free collateralized borrowing/lending. FX swaps do not incorporate an open currency position. More so, they assume that the associated counterparty, credit, liquidity risks, and market risks are negligible.

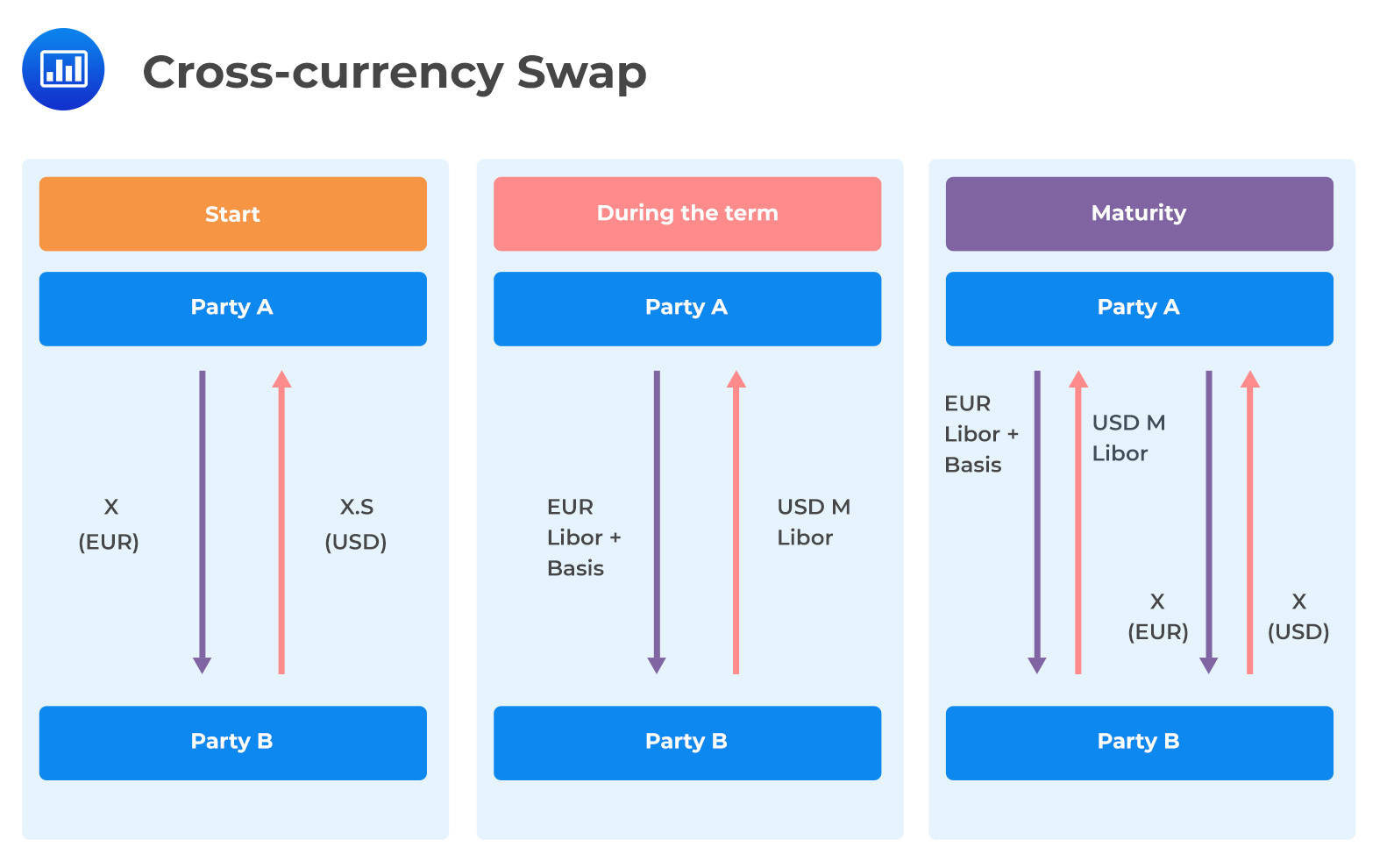

A cross-currency swap is an over-the-counter (OTC) derivative presented in a contract’s form between two parties who purpose to exchange interest payments and principal in different denominated currencies. Typically, in a cross-currency swap, principal and interest in a particular currency are exchanged for interest payments and principals in a different currency. During the agreements’ term, the interest payments exchange is done at fixed intervals. Usually, cross-currency is highly customized and can consist of fixed, variable interest rates, or both.

FX swaps and cross-currency swaps are both derivative instruments utilized in the hedging of foreign currency exposures, but there are some differences

Let’s consider a European institution borrowing a one-year loan from its local domestic bank to fund its operations abroad in the U.S. For currency risk hedging, the institution chooses to enter a one-year currency swap (EUR/USD) with a market counterparty. As such, the institution swaps a specified amount of Euros from U.S dollars at the current spot rate, with the agreement of getting the funds swapped back at the same price rate in one year.

Since the European institution does not technically own the U.S. dollar, it instead pays back U.S. Libor as interest while receiving the Eurobond offered rate (Euribor) from the counterparty. Typically, this is as per the covered interest rate parity (CIP). Practically, when the demand for the dollar is high, the lending counterparty of the dollar will request to be paid a price premium. This is known as a “cross-currency basis.” The European institution will payout U.S Libor and, in return, receive Euribor plus the cross-currency basis.

Assume that the current U.S. Libor is 3.2%, and Euribor is -0.8%. This implies that the cost for the EUR/USD currency swap to say a European firm is 4%. That is, it not only pays out 3.2% on the dollar interest but also pays out 0.8% on the Euro interest since it is negative. This leads to a dollar shortage, and the counterparty quotes a “basis of -0.8%” The new swap for the European institution becomes:

$$ =(3.2\% \text { of the dollar interest}+0.8\% \text{ of Euro interest}+0.8\% \text{ currency basis}=4.8\%) $$

The factors that determine the cross-currency swap basis include:

The cross-currency basis is the basis spread added primarily to the U.S. dollar LIBOR when the USD is funded through foreign exchange (FX) swaps using the Japanese yen or the euro as a funding currency. Principally, the basis in cross-currency swaps should be zero, unless there are variations in credit risk ingrained in the underlying reference rates of one currency relative to another.

In practice, there is a variation in the credit levels between firms that are always able to finance in USD Libor flat and those which are always able to finance in foreign currency Libor flat. Thus, the payment in USD Libor-flat rate cannot be exchanged for the receipt in the foreign currency Libor-flat rate.

Because of financial conditions in the US and foreign country markets, it is natural for market players to consider that the credit reflected by USD Libor flat is different from that by foreign currency Libor flat. In this sense, the basis in cross-currency swaps is determined by the difference in credit levels reflected by USD and foreign currency Libor.

This is the dominant factor in determining the short-term level of basis according to the market players. In the most recent past, the cross-currency basis has been widening globally. The increased demand for U.S. dollars has driven this as a result of the monetary policy divergence between the U.S. and similar economically stable countries. Non-U.S. investors have increased their investments in USD-denominated assets, and the portion of these investments that are hedged for FX risk or funded via FX swaps exerts a widening pressure on the basis.

Additionally, there has been a drop in the supply of the U.S dollars from foreign reserve sovereign/managers wealth funds versus the fall in emerging currency depreciation and commodity prices, causing the cross-currency basis to widen.

Changes in the global bank’s activities lower the market liquidity in the FX swap market in various ways. Newly introduced regulations, such as leverage ratio requirements, have reduced the appetite for market-making and consequently lowering the market liquidity. Moreover, the introduction of a leverage ratio requirement would reduce arbitrage trading activities between the FX swap market and the money market due to the increased cost of expanding balance sheets. The transaction volume in the FX swap market reached a peak at the beginning of 2014 and has been leveling off.

In addition to the direct impacts of regulatory reforms, the increased uncertainty of USD funding rates at quarter-ends decrease global banks’ market-making activities for FX swaps with longer tenors. This is because the FX swap market makers regularly cover their positions using short-term FX swaps that have relatively high liquidity. Thus, under uncertainty regarding quarter-end rates, it is difficult for market makers to quote bid/ask prices for term instruments over quarter-ends with narrow spreads, which seems to lower the market liquidity.

The reduced appetite for arbitrage trading and market-making activities and the decline in market liquidity are thought to amplify the cross-currency basis widening. The basis quickly widens under small demand/supply shocks.

Covered interest rate parity is defined as a hypothetical condition where the correlation between interest rates, spot and forward currency rates of two states are equal once the foreign currency risk is hedged. That means that there is no chance for arbitrage when using a forward contract under CIP.

Basically, in CIP, the spot exchange rate and cash market interest rates can be larger than the ones for FX derivatives. This shifts the currency swap and FX swaps that controls forward exchange rates away from CIP, thus providing an outcome of a non-zero basis. Such changes should typically immediately result in arbitrage transactions, bringing the basis back to zero. This is because, in the real world, CIP arbitrage is commonly treated as riskless.

$$ \cfrac {\text F }{\text S } =\cfrac { 1+\text r}{ 1+{\text r^{*}}} $$

Where:

\(S\) is the spot exchange rate in US dollar per foreign currency

\(F\) is the corresponding forward exchange rate

\(r\) is the US dollar interest rate

\(r*\) is the foreign currency interest rate.

Assume that a mid-market USD/CAD spot exchange rate is 1.4500 CAD with a one-year forward rate of 1.4380 CAD. Additionally, there is a 3% USD and a 4% CAD risk-free interest rate. Find out if the covered interest rate parity between the two currencies holds.

We need to establish whether:

$$ \cfrac {\text F }{\text S } =\cfrac { 1+\text r }{ 1+{\text r }^{ * } } $$

The ratio of forward rate to spot rate:

$$ \cfrac { F }{ S } =\cfrac { 1.4380 }{ 1.4500 } =0.99 \text { USD/CAD} $$

The ratio of the rate of returns:

$$ =\cfrac { 1+\text r }{ 1+{\text r }^{ * } } = \cfrac { \left( 1+3\% \right) }{ \left( 1+4\% \right) } =0.99 \text { USD/CAD} $$

The two values calculated are approximately equal; thus, the covered interest rate parity holds.

Given a spot rate of interest of 2.26 USD/EUR, with a U.S dollar interest rate of 3% and Euro currency interest rate of 5%, calculate the forward exchange rate for one year, if the covered interest rate parity holds.

The formula is the interest rate parity holds is as follow:

$$ \cfrac {\text F }{\text S } =\cfrac { 1+\text r }{ 1+{\text r }^{ * } } $$

Rearranging the equation:

$$ \text{F}=\text{S}\cfrac { 1+ \text r }{ 1+{\text r }^{ * } } $$

$$ \text{F}=2.26×\cfrac {1+0.03}{1+0.05}=2.2170 \ $/€ $$

For the covered interest rate parity to hold the exchange rate must be 2.2170 $/€.

The basis, \(b\), is the amount by which the interest rate on one of the legs has to be modified to match the pricing of FX swaps observed in the market:

$$ F-S=S \cfrac {(1+r+b)}{(1+r^∗ )}-S $$

We may also rearrange the equation as follow:

$$ b≡\cfrac{(F-S)}{S}-(r-r^∗ ) $$

Although banks have strengthened their balance sheets and regained easy access to funding since the great financial crisis, CIP is still violated. As mentioned earlier, CIP holds that the interest rate differential between two currencies in the money markets should be the same as the differential between the forward and spot exchange rates. Otherwise, arbitrageurs could make a seemingly riskless profit.

Similarly, we said that the cross-currency basis indicates the amount by which the interest paid to borrow one currency by swapping it for another differs from the cost of directly borrowing this currency in the cash market. A non-zero cross-currency basis indicates a violation of CIP.

The cross-currency basis has been persistent since the GFC, indicating CIP violations. In the following section, we discuss these violations broadly in terms of hedging demand and tighter limits to arbitrage.

The demand for FX swaps is driven by hedging of open FX positions. Demand from non-financial firms, banks, and institutional investors make up the primary sources of hedging demand. These sources are insensitive to the size of the basis, and, hence, exert sustained pressure on it even when it is nonzero. In the next session, we discuss the structural causes of demand for foreign currency hedges:

Banks have commonly been known for being the chief players in running currency mismatches on their balance sheets. Given banks’ core deposit base, banking systems may be structurally short or long in specific currencies. A foreign currency funding shortfall can then be managed by borrowing cash in money markets and the bond market. FX swaps can be used to resolve the remaining gaps between banks’ assets and liabilities in a given currency. The unresolved gaps between banks’ liabilities and assets in each currency are referred to as closed currency derivatives, and an example is FX swaps. This depicts violations of covered interest rate parity.

For strategic hedging of foreign currency, institutional investors use swaps. An improvement has been registered in recent times in funding flows and cross-currency investments as a result of credit and term spread compression related to unconventional monetary policies in most of the countries. The hedge ratio for investors is usually insensitive to hedging costs and tends to move slowly over time. Therefore, anything that motivates the investors to reduce or increase their investments on foreign currency seemingly exerts pressure on the basis, resulting in CIP violation.

A CIP violation comes about as non-financial firms seek to borrow through opportunistic ways in markets where there is a narrower credit spread. It is of relevance when there is systematic variation in credit spread. For example, most U.S. companies seeking dollars have been issuing euros currency to take the opportunity of the very attractive spreads in that currency and have the proceeds swapped into dollars. This makes it possible for them to avoid currency mismatches in euros while using the dollars for their business activities. Essentially, they borrow dollars and lend Euros through the swap market.

Arbitrage limits have been tightened by structural changes, especially on how market participants price the market, counterparty, credit, and liquidity after the Great Financial Crisis. In this scenario, the balance sheet is not free. Instead, it is rented.

Due to tighter management of threats and associated balance sheet constraints, the arbitrage incurs a cost per unit of balance sheet. The cost incurred is passed on to FX swaps pricing, in which a premium is introduced due to swap market imbalances. One of the outcomes is that the spot-forward relationship in the currency draws out of line with covered interest parity (CIP).

Typically, arbitrage can pose a lot of risks and high costs. An arbitrageur must expand its balance sheet, sustain credit risks in both investing and borrowing, and probably undergo mark-to-market and liquidity threats in the positions’ valuation. Post-crisis, participants have been able to manage these actual costs and risks that are in existence at all times. There has been increased pressure from creditors, shareholders, and authorities on the pricing of risks based on their relevant market after the Great Financial Crisis.

Also, dynamics in regulation have emphasized market pressures for the need for tighter management of balance sheet risks. More so, likely future exposure adjustment charges in U.S. leverage ratios and Basel III need the participants in the market to hold capital in as per their derivatives and other exposures. Mostly, the tighter limits on arbitrage make it complex to have the basis narrowed at any point when it opens due to pressures that reflect the present order imbalances.

Practice Question

Suppose the quarter-market USD/EUR spot exchange rate is 1.2345 EUR with a one-year forward rate of 1.3280 EUR. The market consists of a risk-free rate of 4% USD and 6% EUR, respectively. Establish whether there exists a covered interest rate parity between USD and EUR by choosing which of the following statements is correct.

A. The covered interest rate parity holds and the forward to spot rate is 1.0757.

B. The covered interest rate parity does not hold and the forward to spot rate is 1.0757.

C. The covered interest rate parity holds and the forward to spot rate is 1.0000.

D. The covered interest rate parity does not hold and the forward to spot rate is 0.9811.

The correct answer is B.

The covered interest rate parity is checked using the formula:

$$ \cfrac {\text F }{\text S } =\cfrac { 1+\text r }{ 1+{\text r }^{ * } }$$$$ \text{Ratio of forward to spot rate} =\cfrac {\text F}{ \text S}

=\cfrac {1.3280}{1.2345}=1.0757 $$$$ \text{Ratio of interest rates} =\cfrac {(1+4\%)}{(1+6\%)}=0.9811 $$

The covered interest rate parity does not hold between the USD and EUR since the ratio of forward to spot rate and ratio of returns are not equal, i.e., 1.0757 \(\neq\) 0.9811.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.