Credit Value Adjustment (CVA)

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Explain the motivation for... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

A bank is an intermediary between depositors desiring short-term liquidity and borrowers seeking to finance projects. An unexpected surge in depositors’ cash withdrawals or borrowers showing signs of not being able to repay their loans makes depositors concerned over the solvency of the bank.

The following standard policy tools can be sources of bank failures:

Major dealer banks in the recent financial crisis suffered from the new forms of bank runs. Dealer banks are often considered too big to fail since they are mostly parts of large, sophisticated organizations, and their failures can damage the economy.

The main lines of a dealer bank’s business are:

For simplicity, large dealer banks are treated as members of a distinct class despite there being many significant disparities in many aspects. The most insignificant lines of business of these dealer banks include securities markets, securities lending, repurchase agreements, and derivatives.

Besides, dealer banks engage in proprietary trading when they speculate on their accounts. Various other dealer banks operate internal hedge funds and private equity partnerships as part of their asset management businesses, by effectively acting as general partners with limited-partner clients.

There is always intermediation by dealer banks between securities issuers and investors in the primary market, and among investors in the secondary markets. Sometimes acting as an underwriter, a dealer purchases equities or bonds from an issuer and, over time, sells them to investors in the primary markets.

Sellers hit the dealer’s bid prices, while buyers hit the dealer’s asking prices in the secondary markets. The intermediation of OTC securities markets is dominated by dealer banks, covering bonds issued by corporations, municipalities, specific national governments, and securitized credit products.

Furthermore, interdealer brokers and electronic trading platforms intermediate trade between dealers in some securities. Dealers are also active in secondary equity markets despite public equities being easily traded on exchanges. Speculative investing is popular among banks with dealer subsidiaries and can partly be aided by the ability to observe the inflow and outflow of capital from certain securities classes.

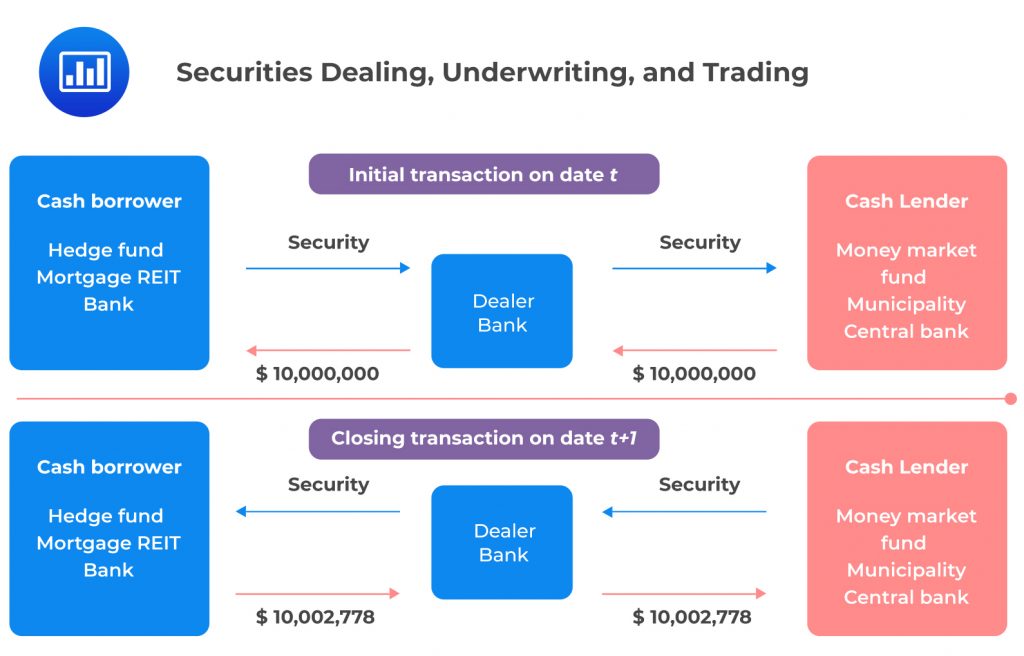

Repos markets are likewise good intermediation points for securities dealers. A counterparty posts government bonds, corporate bonds, government-sponsored enterprises’ securities, or other securities like CDOs as collateral against the performance of a borrowed or lent loan.

Most repos are short-term, typically overnight, and are commonly renewed with the same dealer. A haircut that reflects the securities’ risk or liquidity mitigates a repo’s performance risk.

Some repos are tri-party for counterparty risk requiring mitigation. Tri-party repos are contracts where a third entity (apart from the borrower and lender) acts as an intermediary between the two parties to the repo. Typically, the third party is a clearing bank holding the collateral and returns the cash to the trader, thereby facilitating the trade and somewhat insulates the lender from the borrower’s default risk.

Some repos are tri-party for counterparty risk requiring mitigation. Tri-party repos are contracts where a third entity (apart from the borrower and lender) acts as an intermediary between the two parties to the repo. Typically, the third party is a clearing bank holding the collateral and returns the cash to the trader, thereby facilitating the trade and somewhat insulates the lender from the borrower’s default risk.

The contracts involving transferring financial risk from one investor to another are called derivatives. They are traded OTC on exchanges. OTC derivatives can be customized to suit a client’s needs since they can be privately negotiated. For most OTC derivatives trades, one counterparty must be the dealer. It usually lays off most or all the risk of its client’s inflated derivatives positions by running a matched book, profiting on the differences between bid and offer terms.

Proprietary trading is conducted in OTC derivatives markets by dealer banks as in their securities business. The market value measures the notional amount of an OTC derivatives contract, and for bond derivatives, the measure is the face value of the asset whose risk is transferred by the derivative.

All derivatives contracts must have a total market value of zero as an accounting identity, which implies that there should be an equal number of positive and negative positions. Wealth is transferred by derivatives from one counterparty to another rather than directly added or subtracted from the total stock of wealth.

Fractional costs of bankruptcies can lead to net losses caused by derivatives. Also, the risk is socially transferred from those ill-equipped to bear it to others who are well equipped to bear the risk. There is also a further risk of the counterparty failing to meet its promised payments.

The amount of exposure to default as a result of counterparties failing to perform their contractual obligations is a useful gauge of counterparty risk in OTC markets. Collaterals reduce these exposures.

Under normal circumstances, the trades of various OTC derivatives between a given pair of counterparties are legally combined between the two counterparties under a master swap agreement. The trades are duly aligned to the standards set by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

There was a reduction in the range of acceptable forms of collateral that dealers took from their OTC derivatives counterparties, as the 2007 financial crisis deepened. According to statistics, cash was the form of collateral for over 80% of collateral for these agreements.

An example of an OTC derivative is a call option whereby an investor buys an asset at a prearranged price, protecting the investor from risks related to the cost of acquiring the asset.

Numerous large dealers are active prime brokers for hedge funds and other large investment firms. They provide customers with a variety of services ranging from securities holding management, clearing, and cash management services to securities lending, financing, and reporting.

By lending securities from prime brokerage customers, additional revenue gets generated by the dealer bank.

The large asset-management divisions often found in dealer banks are for the institutional and wealthy individual clients’ needs. The divisions hold securities for clients, oversee cash, and provide alternative investment vehicles like private equity partnerships often managed by the same bank.

A limited partner in an internal hedge fund perceives a large dealer bank to be more stable as compared to a stand-alone hedge fund because the dealer bank might voluntarily support an internal hedge fund at a time when the hedge fund needs financial support.

Dealer banks have made an extensive application of off-balance-sheet financing. A good example is a financial institution originating or buying residential mortgages and other loans financed by the sale of the loans to a financial corporation set up for this express purpose. The proceeds of the debt issued by the special purpose entity to third-party investors pay the sponsoring bank for the assets.

Due to minimal regulatory requirements and accounting standards, dealer banks do not have to treat assets and debt obligations of special purpose entities as if they were on a bank’s own balance sheet. This is because debt obligations of such entities are usually contractually remote from the sponsoring bank.

If the solvency of a dealer bank gets threatened, there can be a rapid change in the relationship between the bank and its derivatives counterparties, prime brokerage clients, and other clients. There are similarities between the concepts at play and those of a depositor run at a commercial bank.

There is also a lack of default insurance by most of the insured depositors exposed to dealer banks as compared to those at a commercial bank, or still, they do not wish to bear the frictional costs of getting involved in the bank’s failure procedures even if they have insurance. The main fundamental mechanisms that lead to the failure of a dealer bank are as follow:

One of the forms through which the assets of larger dealer banks tend to be financed by the banks is the issuing of bonds and commercial paper. The short-term repurchasing agreements have recently financed the purchasing of their securities inventories. The money-market funds, securities borrowers, and other dealers are often the counterparties to these repos.

In case of a failure by the repo creditors of dealer banks to renew their positions en masse, there are doubts about the ability of the dealer banks to finance their assets with enough amounts of new private sector banks. Therefore, the dealer sells its assets hurriedly to buyers aware of the need for a quick sale. This situation is called a fire sale and can lead to lower and lower prices for the assets.

In case the dealer’s initial solvency concerns were prompted by declines in the market values of the collateral asset themselves, an asset fire sale’s proceeds could be insufficient to meet the dealer’s cash needs.

Fatal inferences by participants in other markets of the dealer’s weakened condition could be as a result of a fire sale. During a financial crisis, the financing problems of a dealer bank could be exacerbated. Besides, the fire-sale prices could lower the market valuation of the unsold securities hence lowering the volume of cash that could accrue from repurchase agreements collateralized by those securities, leading to a “death spiral” of further fire sales. Consequently, fire sales by one large bank could set off fire sales by other banks, resulting in systemic risk.

The dealer bank can alleviate the risk of a liquidity loss in the following ways due to a run by short-term creditors:

Teams of professionals are always present for major dealer banks to manage liquidity risk by controlling the distribution of liability maturities and managing the availability of pools of cash and other noncash collateral acceptable to secured creditors.

Broad and flexible lender-of-last-resort financing to large banks is a popular response by central banks to the systemic risk created by the potential for fire sales. The time needed for financial claims to be liquidated bought by such financing on time.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has always provided secured financing to regulated commercial banks through its discount window. However, the discount window is not accessible to dealers, since they are not as regulated as banks.

For the cash that was lost by the exit of repo counterparties and other less suitable funding sources to be replaced, there may be lessening of the extent to which traditional insured bank deposits finance a dealer bank during a solvency crisis.

The cash and securities left by customers in their prime brokerage accounts are sometimes partly used by prime brokers to finance themselves. In the U.K., securities and cash in prime brokerage accounts are generally commingled with assets of prime brokers and are, therefore, available to the prime brokers for their business.

A prime broker in the U.S. must aggregate its clients’ free balances in safe areas of the broker dealer’s business-related activities to service its customers. Alternatively, a prime broker can deposit the funds in a reserve bank account to prevent the comingling of customer and company funds.

The financing provided by prime brokers to their clients is typically secured by the assets of those clients’ prime brokers. In the U.S., the asset of a client can also be used as collateral to finance a dealer bank’s margin loans through re-hypothecation.

The weakening of a dealer bank’s financial position may lead hedge funds to move their prime brokerage accounts elsewhere. The cash liquidity problems of a prime broker in the U.S. can be exacerbated by its prime brokerage business with or without clients running away from the dealer bank.

The dealer could continuously demand a hedge fund cash margin loans backed by securities left by the hedge fund in its prime brokerage account, under its contract with the prime broker.

The prime broker may have to use its cash to meet the demands of other customers on short notice since the running away of prime brokerage customers can leave them with insufficient cash to be pulled from their free credit balances to meet the said demands.

If a dealer bank is perceived to have some solvency risk, the counterparty of an OTC derivative looks for opportunities to reduce its exposures to that of the dealer bank. The following are the mechanisms that are possible in this case scenario:

Novation to another dealer is also a feasible way for a counterparty to reduce its exposure to the dealer, just like in the case of Bear Stearns in 2008, whereby its counterparties sought for novation from other dealers. Often, a collateral posting call is necessary for the OTC derivatives agreement. Furthermore, the increase in collateral is frequently called from a counterparty whose credit rating gets downgraded below a stipulated level.

Terms for the early termination of derivatives are included in the master swap agreements, and this includes one of the counterparties defaulting.

Most OTC derivatives are exempted by law as “qualifying financial contracts” from the automatic stay at bankruptcy, holding up other creditors of a dealer. A significant post-bankruptcy drain on the defaulting dealer is the impact of unwinding the derivatives portfolio of the dealer.

To minimize the incentive of counterparties fleeing from a weak dealer bank, derivatives contracts are granted through a central clearing counterparty, which intervenes between original buyers and sellers of OTC derivatives. The central clearing counterparty protects all losses accruing from defaults by amassing capital from members and collateral against derivatives exposures to its members.

The refusal of the clearing bank to process transactions marks the final step of the collapse of a dealer bank’s ability to meet its daily obligations. A clearing bank extends daylight overdraft privileges to its creditworthy clearing clients in the normal course of business.

The right to offset a contractual right to discontinue making cash payments, thus reducing the account holder’s cash below zero during the day, is always in possession of a clearing bank in case the cash liquidity of the dealer is under scrutiny. This process results after accounting for the value of any potential exposures by the clearing bank to the account holder.

For many years, there have been developments in the policies for prudential supervision, capital requirements, and traditional commercial banks’ failure resolutions, and they have been relatively settled. Policies for reducing the risks possessed by large systematically important financial institutions (SIFIs) have had significant new attention brought to them due to the financial crisis.

In both the U.S. and Europe, increased capital requirements, new supervisory councils, and special abilities to resolve the financial institutions as they approach insolvency are the currently envisioned regulatory changes for financial institutions that are critical for the banking system.

The leading cause of systematic risk in the market is the effect of a dealer bank fire sale on market prices and investor portfolios. To alleviate a financial crisis, lender-of-last-resort financing and capital injections such as those provided by central banks have been used. Such injections can be provided by the Bank of England or the U.S. Treasury Department’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

The policy responses have further taken care of the challenges related to short-term tri-party repos, which are unstable financial sources to a dealer bank. Tri-party clearing banks have incentives that cover their exposures to a dealer bank, limiting the dealers’ access to repo financing and account function clearance. According to Ben Bernanke, who served two terms as Chair of the Federal Reserve, there are possible benefits of a tri-party repo, with less discretion in rolling over a dealer’s repo positions.

Additionally, there is a development of an emergency bank usually financed by repo participants. The bank has direct access to discount-window financing from the central bank, protecting the systemically critical clearing banks from losses in the event of unwinding their positions.

Further, the threat caused by the flight of over-the-counter derivatives counterparties is alleviated through central clearing. Nowadays, several OTC derivatives, such as equities, commodities, and foreign exchange, are centrally cleared.

Practice Question

ClearWater Bank, a large dealer bank, has played a significant role in the OTC derivatives market, the short-term repurchase or repo market, the management and underwriting of securities issuances, and as a prime broker to several major hedge funds. The bank has recently observed a substantial growth in its operations, and its executives have started to rely heavily on some specific financial strategies. The bank’s board of directors is conducting a review to ensure the stability of the institution. During one of the board meetings, an external consultant presented the Basel Committee’s recommendations on early warning indicators for potential vulnerabilities in liquidity positions.

The board members are now discussing which of the bank’s recent activities or changes could be an early warning indicator of a potential liquidity problem.

Which of the following should raise a concern based on the Basel Committee’s recommendations?

A. Credit rating upgrade

B. Increased asset diversification

C. Rapid growth in the leverage ratio with significant dependence on short-term repo financing

D. Decreased collateral haircuts applied to the bank’s collateralized exposures

Solution

The correct answer is C.

A rapid increase in the leverage ratio, especially when the bank is heavily reliant on short-term repo financing, is a potential early warning sign of liquidity issues. This is because while leverage can amplify returns, it can also magnify losses. Relying on short-term repo financing means the bank is dependent on continuous refinancing. If counterparties become wary due to concerns about the bank’s solvency or the quality of its collateral, they might be hesitant to roll over or renew the repos. This could lead to a liquidity crunch for the bank.

A is incorrect: A credit rating upgrade typically indicates increased confidence in the financial health and stability of a bank from the perspective of the rating agency. This is usually seen as a positive sign and is not an early warning indicator of a liquidity problem.

B is incorrect: Increased asset diversification generally indicates that a bank is spreading its risk across various assets, which can potentially reduce the impact of a downturn in any single asset or asset class. Diversification is generally a risk management strategy and not an early warning indicator of a liquidity problem.

D is incorrect: Decreased collateral haircuts might mean that the bank is accepting a higher percentage of the value of the collateral for its exposures. This could increase the bank’s risk if the value of the collateral drops significantly. However, it is not a direct early warning sign of liquidity issues. While it can increase counterparty risks and potential future liquidity needs if the collateral needs to be liquidated, it is not as direct an indicator as option C.

Things to Remember

- The Basel Committee provides guidelines to ensure financial institutions maintain stability, particularly concerning their liquidity positions.

- Leverage can be a double-edged sword: while it can boost returns, it can also intensify losses. High leverage with a dependence on short-term financing is a crucial vulnerability.

- Short-term repo financing demands constant refinancing. Any hesitancy from counterparties to renew can push an institution into liquidity challenges.

Prepare for FRM Part II by evaluating dealer bank business lines, liquidity pressures, and systemic risk factors.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.