Current Issues in Financial Markets

1. Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

This chapter discusses fraud and financial crime risk management in different forms: fraud, money laundering, and terrorism financing.

Internal and external fraud are common types of operational risk banks managed long before the introduction of ORM. Non-financial risk management comprises anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF). These two are responsible for effective control against the risk of terrorism and money laundering.

According to the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) Handbook of the UK, financial crime refers to “any kind of criminal conduct relating to money or to financial services or markets, including any offense involving: fraud or dishonesty; or misconduct in, or misuse of information relating to, a financial market; or handling the proceeds of crime; or the financing of terrorism.“

Financial crime comprises internal and external fraud, money laundering, and terrorism financing.

Internal Fraud: According to BCBS, internal fraud refers to “losses due to acts of a type intended to defraud, misappropriate property or circumvent regulations, the law or company policy, excluding diversity/discrimination events, which involve at least one internal party.”

Internal fraud can be of two types: “unauthorized activities” and “theft and fraud.” “Unauthorized activities” may lead to loss of money in an organization. Indeed, it includes any intentional violation of the law or internal policies perpetrated by a firm’s employees. Examples of unauthorized activities under the Basel event type classification include intentional non-reporting of transactions, mismarking trading positions, or the execution of unauthorized transaction types. Passwords, disclosure of confidential information, or the mis-selling of financial products to vulnerable clients are also examples of unauthorized activities.

On the other hand, “theft and fraud” involve the misappropriation of assets, such as extortion, embezzlement, malicious destruction of assets, bribery, and tax evasion.

External Fraud: According to BCBS, external fraud refers to losses due to acts of a type intended to defraud, misappropriate property or circumvent the law by a third party.

The subcategories of external fraud are “theft and fraud” and “systems security,” which involves hacking damage and theft of information. “Systems security” is particularly becoming prominent as a result of the increasing digitalization of financial services. Since about a decade ago, cyber and information risk management has also evolved into a specialized branch of operational risk management, sometimes called information security risk management (ISR).

Recent studies show that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased (by more than two times) the banks’ exposure to internal and external fraud. The work-from-home program particularly led to an increase in fraudulent wire transfers and email scams.

Different countries may have different laws against money laundering and terrorism financing. In this section, however, we use the definition of the European Union. On May 20, 2015, the European Parliament and Council issued a directive to prevent the use of the financial system for money laundering or terrorist financing. According to article 1 of this directive, money laundering involves any of the following:

The IMF defines terrorism financing as the provision or collection of funds to be used, partly or in full, to facilitate any offense considered by the authorities as a terrorism act.

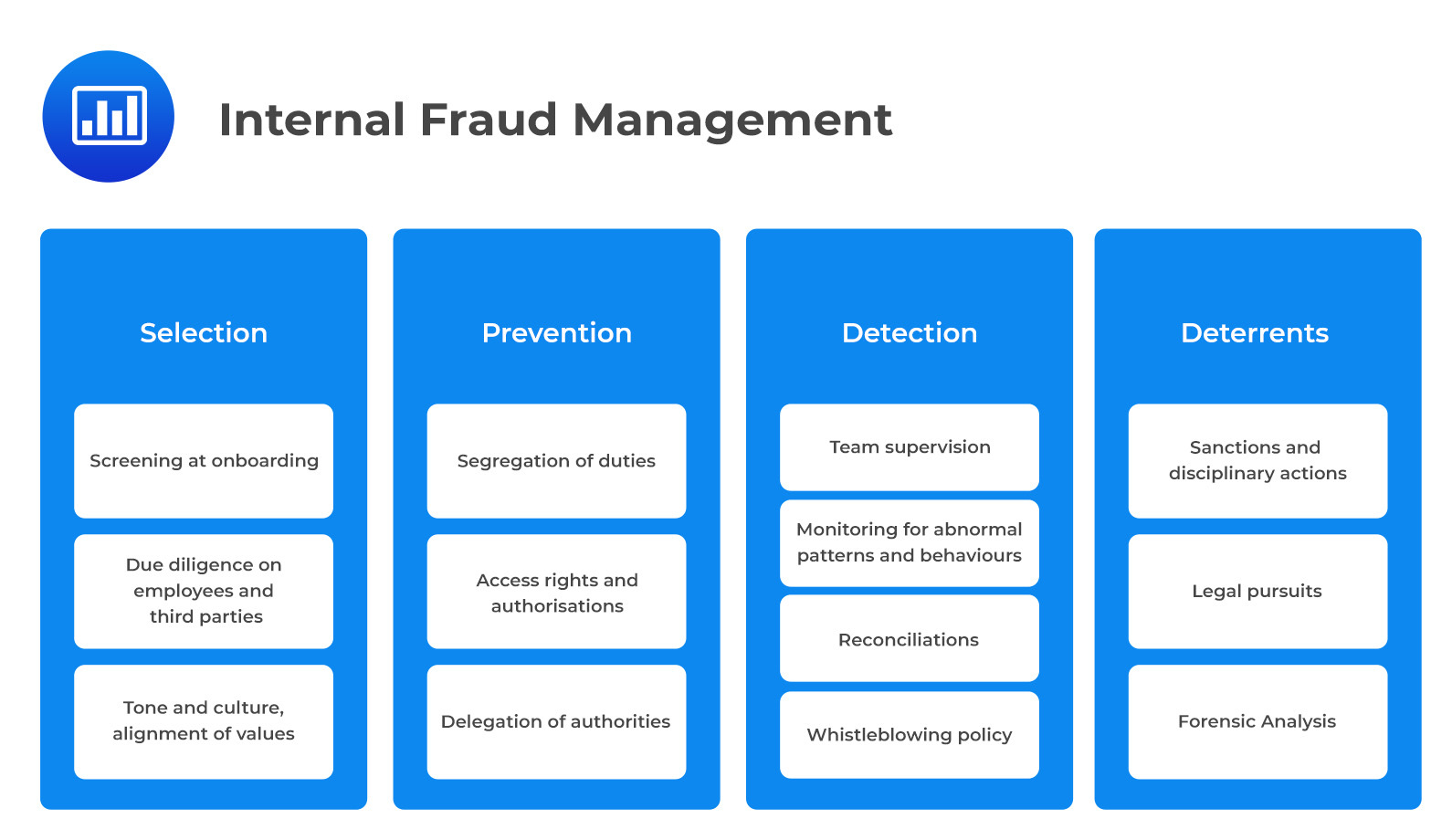

This section will review the prevention and mitigation of internal fraud and anti-money laundering practices.

Historically, the internal audit department was responsible for managing internal and external fraud for banks. Some banks used to have “inspections,” which were orchestrated by a subdivision of the internal audit responsible for detecting, monitoring, and reporting fraud.

In their risk appetite framework, most firms state that they have zero tolerance for internal fraud.

The figure below presents a framework of controls and measures to mitigate internal fraud risks. The framework presented below consists of four components:

External Fraud Management

External Fraud ManagementExternal fraud management shares many of the aspects of internal fraud management. The point of departure is that external fraud management focuses on bad external actors.

Bank robbery, check kiting, fraudulent wire transfers, credit card fraud, and identity theft are examples of external fraud. Misrepresentations of income, assets, and collateral values in loan applications are also classified as fraudulent by most institutions. It is sometimes necessary to subdivide external fraud into first-party and third-party fraud. This helps distinguish between fraud customers commit or those a business partner commits for their own benefit from fraud committed by an external actor, which may affect both the bank and the customer.

It is, therefore, necessary for special teams to manage the different types and actors of external fraud. For example, ensuring security is in place to secure the buildings and assets of the financial institution against robbery. Banks also work with local authorities to handle such issues whenever they occur.

It is common for criminals to disguise the proceeds of their criminal activities into legitimate sources of funds in two or three phases. The following are the three phases of money laundering:

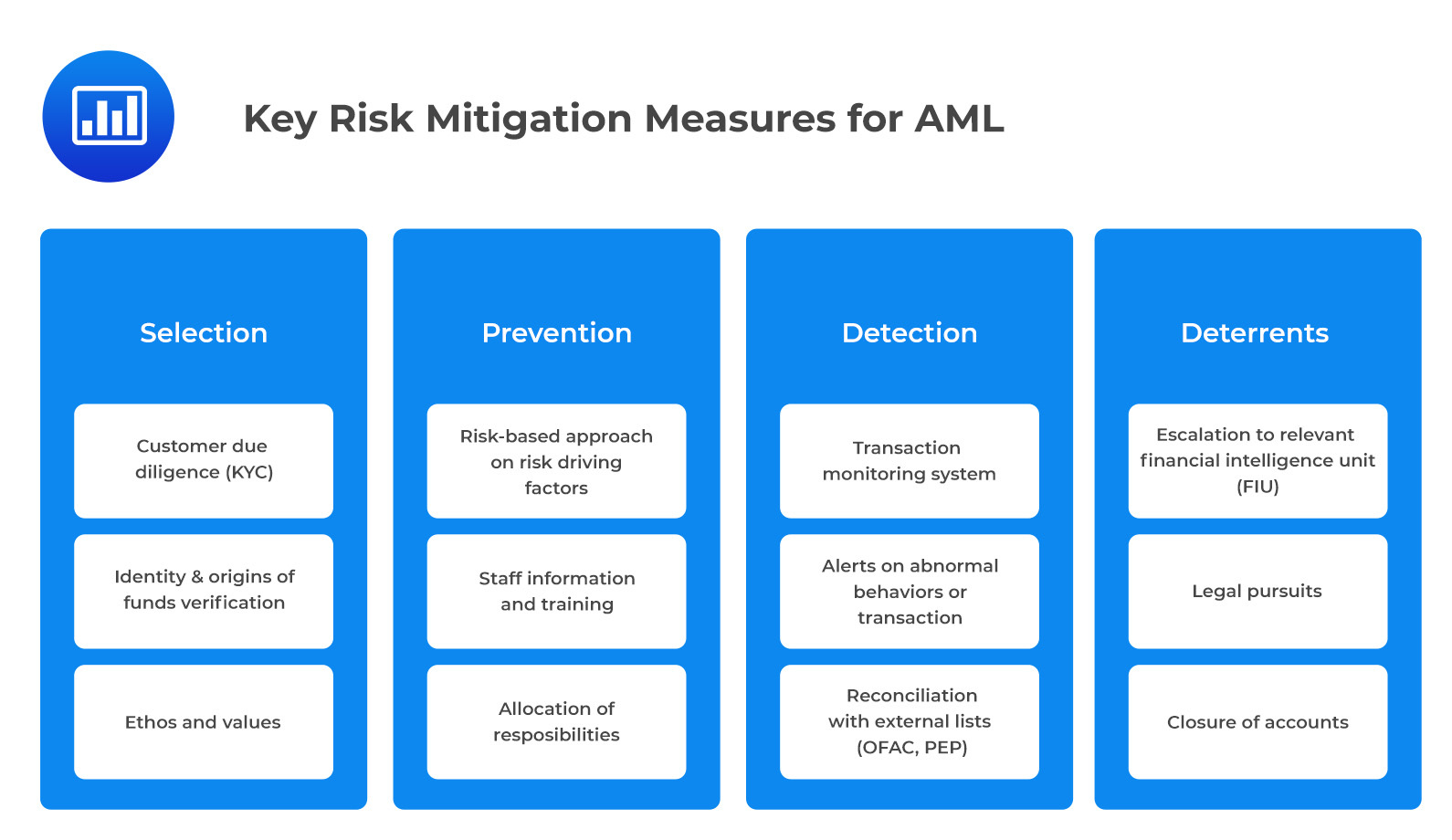

The figure below presents key risk mitigation measures for AML.

Most importantly, customers should be selected appropriately and their documents properly scrutinized and verified (KYC, known as know your customer). Banks should also verify the origins of funds before embarking on any business transactions to ensure that these funds are not linked to any fraudulent activities.

Most importantly, customers should be selected appropriately and their documents properly scrutinized and verified (KYC, known as know your customer). Banks should also verify the origins of funds before embarking on any business transactions to ensure that these funds are not linked to any fraudulent activities.

Regulators recommend a risk-based approach to AML risk management. That is, the higher the risks, the tighter the controls, and vice versa. Customers are categorized as low, medium, or high risk based on associated risk factors which are used as monitoring criteria.

Firms should have robust governance and a prudent money laundering risk officer (MLRO) responsible for the management of AML. In addition, establishing written policies, training employees, and thorough reviews can also contribute to effective AML risk management.

In its 2022 report, the FCA examines financial crime controls at challenger banks, which are fully digital and offer customers the ability to open accounts very quickly. According to FCA, there is a risk that accounts opening information is insufficient to identify higher-risk customers. The following are some key findings highlighted by UK regulators:

According to the banking and compliance press, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) fined USAA Federal Savings Bank (FSB) $140 million for failing to implement and maintain a BSA/AML compliance program.

Deficiencies pointed out include inadequate internal controls; detection, evaluation, and reporting of suspicious activity; staffing; training, and third-party risk management, as well as significantly understaffed BSA/AML compliance departments.

This is a common practice in banking, especially when many workloads are coupled with tight deadlines. However, USAA failed to train or ensure contractors had the necessary qualifications, worsening the situation.

It has been reported that the new transaction monitoring system implemented by USAA FSB is “too sensitive and generates an unmanageable number of alerts and cases.”

An important lesson from this case is that heavy regulatory fines do not occur by accident: They result from accumulating failures and procrastinating about implementing the necessary changes to meet regulatory requirements. Due to the difficulty and discomfort associated with transformations, most firms delay implementing changes in response to regulatory findings until the last minute. This may be too late, as in the case of USAA.

A weak control environment can attract fines by regulators anywhere in the world, as has happened in the US, UK, and Asia. In Asia, for example, regulators charged banks fines totaling $5.1 billion for failing to comply with AML laws.

Banks are required to review, verify, and report suspicious activity in response to regulatory findings and sanctions. An AML risk management framework should incorporate technology and automation for detection and alerts as well as proper recording of false positives and false negatives. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic changed customer and business behavior, particularly with the rise of remote transactions, which makes it more difficult for financial institutions to detect anomalies. Fraud risk management and AML are constantly changing as new opportunities present themselves for fraudsters in new economic and business environments.

Practice Question

Given the lessons from the USAA FSB case, which of the following best represents a key consideration for financial institutions seeking to maintain a robust AML program?

A. Employing third-party contractors inherently improves AML monitoring capabilities. B. Rapid account growth is a valid justification for non-compliance with AML standards.

C. Introducing new transaction monitoring systems, regardless of their sensitivity, will always enhance AML compliance.

D. Instituting adequate controls is crucial, especially when using automated detection systems, to manage the volume of alerts and ensure they do not produce an overwhelming number of false positives or false negatives.

Solution

The correct answer is D.

The USAA FSB case clearly illustrates the importance of having adequate controls, particularly when utilizing automated detection systems. The challenge that the bank faced with 90,000 unreviewed alerts and nearly 7,000 unreviewed cases was primarily due to their newly introduced transaction monitoring system being overly sensitive. This emphasizes that while automation can aid in detecting potential AML violations, it’s critical to ensure that these systems are well-calibrated to manage the number of alerts and minimize false positives and negatives.

A is incorrect because simply employing third-party contractors does not guarantee improved AML monitoring. In the case of USAA FSB, they utilized third-party contractors due to staffing shortages but failed to train them adequately in AML compliance matters, which compounded their problems.

B is incorrect because rapid account growth should never be an excuse for non-compliance with AML standards. Financial institutions must scale their compliance programs in tandem with their growth to ensure they continue to meet all regulatory requirements.

C is incorrect as the case demonstrates that merely introducing new transaction monitoring systems does not guarantee improved AML compliance. The new system at USAA FSB was overly sensitive, producing an excessive number of alerts that overwhelmed their compliance processes. This highlights the importance of ensuring that any new system introduced is properly calibrated and tested to suit the institution’s needs.

Things to Remember

- Automation isn’t flawless: The USAA FSB case underscores the importance of calibrating automated detection systems. While they can be powerful tools, they must be optimized to avoid excessive false positives and negatives.

- Quality over quantity: It’s not about the number of alerts but their quality. An overwhelming number of alerts, if not actionable, can hamper the efficiency of an AML program.

- Training is key: Even with third-party assistance, training is paramount. Outsourcing without ensuring the contractors’ understanding of AML can exacerbate compliance issues.

- Scalability with compliance: Rapid growth of accounts or transactions requires scalable compliance mechanisms. Growth should never be a reason for AML non-compliance.

- System implementation needs oversight: Introducing new monitoring systems requires thorough testing and calibration, ensuring they are tailored to the institution’s specific requirements and challenges.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.