Credit Value Adjustment (CVA)

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Explain the motivation for... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

Derivatives are financial contracts whose value is linked to the performance of underlying assets, indices, or market conditions. These underlying elements can range from commodities and stocks to interest rates and currencies. Derivative transactions often involve commitments to make payments or buy or sell securities at future dates, which can range from a few weeks to several years. This future-oriented nature causes the value of a derivative to fluctuate over time, in tandem with the changes in the underlying assets or indices.

Counterparty credit risk, also known as counterparty risk, arises in derivative transactions due to the possibility of one party becoming insolvent and thus failing to fulfill its contractual obligations. This risk is intrinsic to derivatives due to their nature of binding two parties in a contract where each has claims against the other, often in the form of evolving cash flows.

Key features of counterparty credit risk include the following:

The default of a major player in the derivatives market, such as the case of Lehman Brothers, underlines the severe implications of counterparty credit risk. The evolving nature of market conditions and underlying assets means that the risk profile of a derivative can change significantly over its lifetime, requiring continuous risk management and reassessment.

Exchange-traded derivatives, a key component of the financial derivatives market, offer distinctive characteristics that cater to a range of investment and hedging needs.

Standardization

At the core of exchange-traded derivatives is the principle of standardization. This feature entails setting uniform specifications for contracts, including factors like contract size, expiration dates, and, in the case of options, strike prices. A practical example of this standardization can be seen in the futures market, such as the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), where a standard oil futures contract might be pegged at 1,000 barrels, with delivery dates specified for particular months like March, June, September, and December.

This standardization simplifies the trading process, making these derivatives more accessible and understandable for a wider range of market participants. Additionally, it fosters a level of predictability and consistency in the market, as traders and investors can reliably anticipate the contract terms they will encounter.

Market Efficiency and Liquidity

Exchange-traded derivatives are known for promoting market efficiency and enhancing liquidity. The centralization of trading on exchanges means that buying and selling these derivatives become more straightforward, allowing participants to enter and exit positions with ease. An illustration of this liquidity can be seen in the trading of E-mini S&P 500 futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). These contracts are highly liquid, enabling large-volume trades with minimal price impact, which is beneficial for both individual and institutional traders.

Moreover, the aggregation of trades on a single platform contributes to the efficient dissemination of price information, ensuring that prices reflect current market conditions and consensus valuations. This efficient price discovery process is vital for the fair valuation of assets and risk management.

Price Transparency

The transparency of pricing in exchange-traded derivatives markets is another significant advantage. For example, in the equity options market on the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), all market participants have access to current bid and ask prices, as well as information on the most recent transaction prices. This transparency is crucial in helping investors make informed trading decisions and ensuring that no party has an undue advantage due to asymmetric information.

Contract Closure

The ease with which positions in exchange-traded derivatives can be closed is a key benefit. Given the standardization of contracts and the liquidity of the market, closing a position is typically a matter of executing a counter trade. For instance, an investor who buys a gold futures contract and later decides to close the position can do so by simply selling an equivalent futures contract. The prevalence of buyers and sellers and the uniformity of contract terms facilitate this process.

Maturity

Exchange-traded derivatives often have standard maturities, usually extending to a few months at most. This feature is contrasted with OTC derivatives, which can have much longer and negotiable maturities. Standard maturities in exchange-traded derivatives, such as quarterly delivery months for U.S. Treasury bond futures traded on the CME, play an essential role in trading strategies and risk management. Traders need to be cognizant of these maturity dates as they have implications for the timing of cash flows and risk exposure.

The structure and functioning of exchange-traded derivatives, characterized by standardization, market efficiency, liquidity, price transparency, and specific maturity profiles, make them a vital part of the financial markets. They cater to a broad spectrum of needs, from basic hedging to complex trading strategies, and are instrumental in providing a stable, transparent, and efficient market environment. The examples cited above underscore the practical utility and advantages of these features in real-world trading scenarios.

Over-the-Counter (OTC) derivatives, representing a significant portion of the derivatives market, are notable for their flexibility and customization but come with unique risks and challenges.

Broad Classes and Customization

OTC derivatives encompass a diverse range of products, including interest rate derivatives, foreign exchange derivatives, equity derivatives, commodity derivatives, and credit derivatives. Unlike exchange-traded derivatives, OTC derivatives are often less standardized and are typically traded bilaterally between two parties. This bilateral nature allows for a high degree of customization to meet specific needs. For instance, a company might use a custom OTC derivative to hedge the production or use of an underlying asset at specific dates, an option that might not be available in the standardized environment of an exchange

Private Negotiation and Collateralization

OTC derivatives are traditionally negotiated and traded directly between two parties, such as a dealer and an end user, or between two dealers, without the involvement of an exchange or other intermediaries. These contracts are often not actively traded in secondary markets and lack the transparency typically found in exchange-traded derivatives. Legal documentation for these derivatives is bilaterally negotiated, although certain standards have developed over time.

A significant portion of OTC derivatives are collateralized, with parties pledging cash or securities against their derivative portfolios to neutralize net exposure and mitigate counterparty risk. However, this practice introduces additional legal and operational risks, funding costs for posting collateral, and potential liquidity risks if the required collateral cannot be sourced in time.

Risks and Challenges

One of the main disadvantages of OTC derivatives is the challenge in unwinding a transaction. To avoid future counterparty risk, a customer must typically deal with the original counterparty, who may quote unfavorable terms due to their privileged position. Assigning or novating the transaction to another party usually requires permission from the original counterparty, highlighting a lack of fungibility in OTC transactions.

Furthermore, OTC derivatives may give rise to additional ‘basis risk.’ For example, the mismatch of maturity dates between a custom OTC derivative and an available exchange-traded derivative can create a basis risk, where the hedge does not perfectly offset the underlying exposure.

$$\small{\begin{array}{l|l|l}

& \textbf{Exchange-Traded Derivatives}& \textbf{OTC Derivatives} \\

\hline

\text{Standardization} & \text{Highly standardized contracts} & \text{Less standardized, more flexible} \\

\hline

\text{Trading Mechanism} & \text{Through centralized exchanges} & \text{Bilaterally between two parties} \\

\hline

\text{Market Efficiency} & \text{Enhances market efficiency and liquidity} & \text{Not actively traded in secondary markets} \\

\hline

\text{Price Transparency} & \text{Transparent and accessible pricing} & \text{Pricing often private and less transparent} \\

\hline

\text{Contract Closure} & \text{Easy to buy and sell equivalent contracts} & \text{Custom terms may complicate closure} \\

\hline

\text{Maturity} & \text{Standard maturities; at most a few months} & \text{Negotiable; often many years} \\

\hline

\end{array}}$$

Market Significance and Evolution

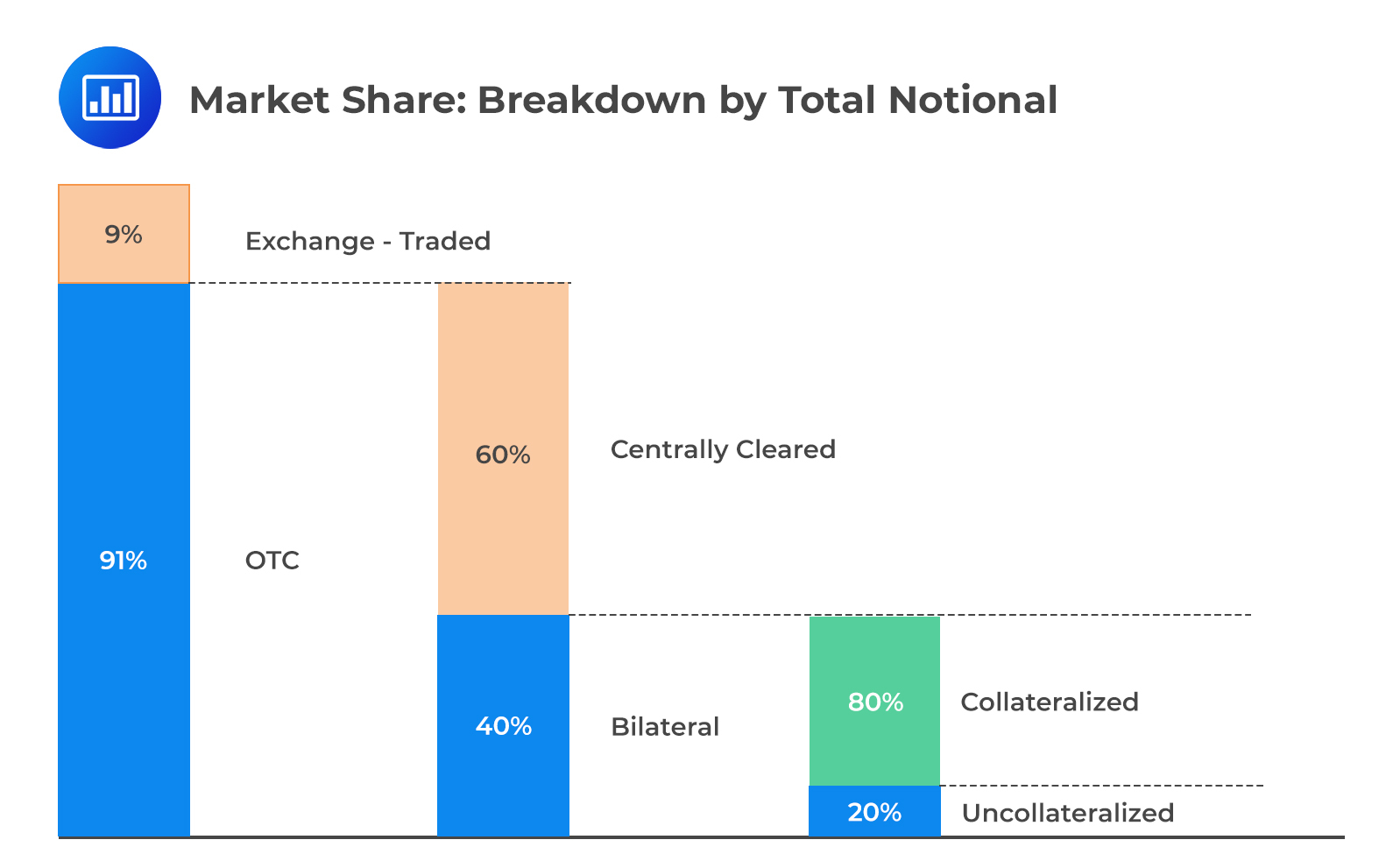

OTC derivatives are a substantial part of the derivatives market. Despite their complexities, they are widely used by large companies to manage financial risks due to their ability to tailor to bespoke needs. The market for OTC derivatives has evolved significantly, with around 60% of the notional amounts outstanding (mostly interest rate contracts) reported by dealers as being centrally cleared. This shift towards central clearing has impacted the OTC derivatives market, aiming to reduce risks associated with these instruments.

Clearing in the context of derivative transactions refers to the processes undertaken after a transaction has been executed and before it has been completely settled. It involves the computation and often netting of payment obligations between the parties involved. Clearing encompasses the period between the execution and settlement of a transaction. (Clearing takes place immediately after the trade, involving a comprehensive review of the terms of the deal, along with managing transactions through margining, cash flow exchanges, and related activities. Settlement marks the ultimate stage in this process, where the actual transfer of securities or money between parties is executed.)

The timeframes associated with classically-exchange-traded derivatives typically range from a few days, as seen in spot equity transactions, to a maximum of a few months, such as with futures contracts. A distinctive characteristic of many OTC derivatives is their protracted settlement periods due to their extended maturities. In sharp contrast, exchange-traded products tend to conclude settlements within days or, at most, a few months. In the case of OTC derivatives, the clearing process often extends over several years and, in some instances, even decades. This discrepancy underscores the increasing significance of OTC clearing and partly explains why most of such instruments are now being put under some type of central clearing.

Clearing can be bilateral or central. In bilateral clearing, the counterparties to an OTC contract handle the risk management processes themselves. However, in central clearing, a third party takes on the responsibility of managing counterparty risk, which may include collateral management. Derivative exchanges now generally come with an associated Central Counterparty (CCP) that performs the central clearing function.

Historically, the OTC derivatives market has been bilaterally cleared, but there has been an increasing trend toward central clearing for such derivatives.

One essential aspect of clearing is counterparty risk, which emerges when a party fails to uphold its contractual responsibilities. This risk is managed differently depending on the type of clearing. For centrally cleared transactions, the risk management functions are typically taken care of by the associated CCP. In contrast, bilateral clearing requires the contracting parties to manage these risks themselves.

Central clearing can be viewed as a logical extension of exchange trading; however, it necessitates a level of standardization that may not be attainable for all OTC derivatives. While the quantity of OTC derivatives subject to central clearing is on the rise, a substantial proportion will continue to be cleared bilaterally. In bilateral markets, alternative approaches like multilateral compression can also be employed, effectively harnessing certain aspects of central clearing functionality.

Participants in the derivatives market encompass a broad spectrum, from large, globally-operating dealers and G-SIBs to small end users like corporations and specialized financial entities. Each participant engages with the derivatives market with different objectives, capabilities, and regulatory obligations, thereby shaping the dynamics and structure of the market.

Large Players: Dealers and Globally Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs)

Medium-Sized Players: Regional Banks and Financial Institutions

End Users: Corporates, Sovereigns, and Smaller Financial Institutions

In the realm of OTC derivatives end users, a distinctive scenario involves certain counterparties with exceptionally high creditworthiness, such as sovereigns, supranational entities, or multilateral development banks. Historically, these entities have enjoyed favorable arrangements with banks, wherein they receive collateral without the obligation to post it, possibly contingent upon rating triggers that could necessitate collateral posting in case of downgrades. However, such arrangements have become increasingly expensive in the present environment, primarily due to the associated funding and capital requirements.

Furthermore, within the OTC derivatives market, there is a plethora of third-party entities offering a range of services. These services encompass settlement, margining, collateral management, software solutions, trade compression, and clearing services. These third-party providers enable market participants to mitigate counterparty risk and the various risks linked to counterparty risk, including legal considerations, while simultaneously enhancing operational efficiency in these domains.

Collateralization in the derivatives market involves the pledging of assets (usually cash or securities) by parties in a trade to secure performance and mitigate counterparty credit risk—the risk that one party may default on the contract. Collateral is used to ensure that parties have a financial safety net in case their counterparty fails to meet the contractual obligations.

Collateral serves two main purposes:

Derivatives can be broadly classified into several groups based on the nature of their transactions and collateralization. These groups are listed below in order of increasing complexity and risk.

The derivatives market is predominantly composed of OTC derivatives, constituting 91% of the total notional value. Within this segment, the majority, or 60%, are centrally cleared, highlighting a market preference for risk mitigation through central clearing parties. The remaining 40% of the OTC market consists of bilateral derivatives, which are direct agreements between two parties. In this bilateral segment, a significant majority, 80%, are collateralized, indicating a strong inclination towards securing transactions and mitigating potential credit risk. However, there is still a notable portion, 20%, that is under-collateralized, reflecting the presence of higher risk exposure within this subset. On the other hand, exchange-traded derivatives, known for their standardized features and regulatory oversight, make up a smaller fraction of the market, accounting for 9% of the total notional value. This distribution underscores a market landscape where OTC derivatives, with their varied risk management structures, dominate while exchange-traded derivatives cater to a specific market niche.

The practice of collateralization provides a means to reduce counterparty credit risk within the derivatives market. It establishes financial safeguards that mitigate the potential consequences of defaults and contributes to market stability. Despite its benefits, the process of managing collateral presents its own set of challenges including funding costs, liquidity management, and compliance with legal and operational requirements. Market participants must weigh these factors carefully when engaging in derivatives trading, ensuring that their risk management strategies are both effective and sustainable.

The practice of collateralization provides a means to reduce counterparty credit risk within the derivatives market. It establishes financial safeguards that mitigate the potential consequences of defaults and contributes to market stability. Despite its benefits, the process of managing collateral presents its own set of challenges including funding costs, liquidity management, and compliance with legal and operational requirements. Market participants must weigh these factors carefully when engaging in derivatives trading, ensuring that their risk management strategies are both effective and sustainable.

The interaction between banks and end users in the derivatives market is characterized by the management of counterparty risk, funding, collateral, and capital. These aspects play out differently for banks and end users, each having distinct strategies and concerns when transacting in derivatives, especially for hedging purposes.

End users, such as corporations, typically engage in derivatives transactions to hedge against various economic risks. Their approach to hedging is often directional, aiming to offset specific economic risks, resulting in portfolios that reflect this targeted hedging strategy. Consequently, they face significant mark-to-market (MTM) volatility, leading to substantial variation in the value of derivatives and associated margin or collateral flows. This volatility is a primary reason why many end users are hesitant to enter into collateral agreements, as the requirement for substantial collateral over a short time horizon can be daunting and financially strenuous.

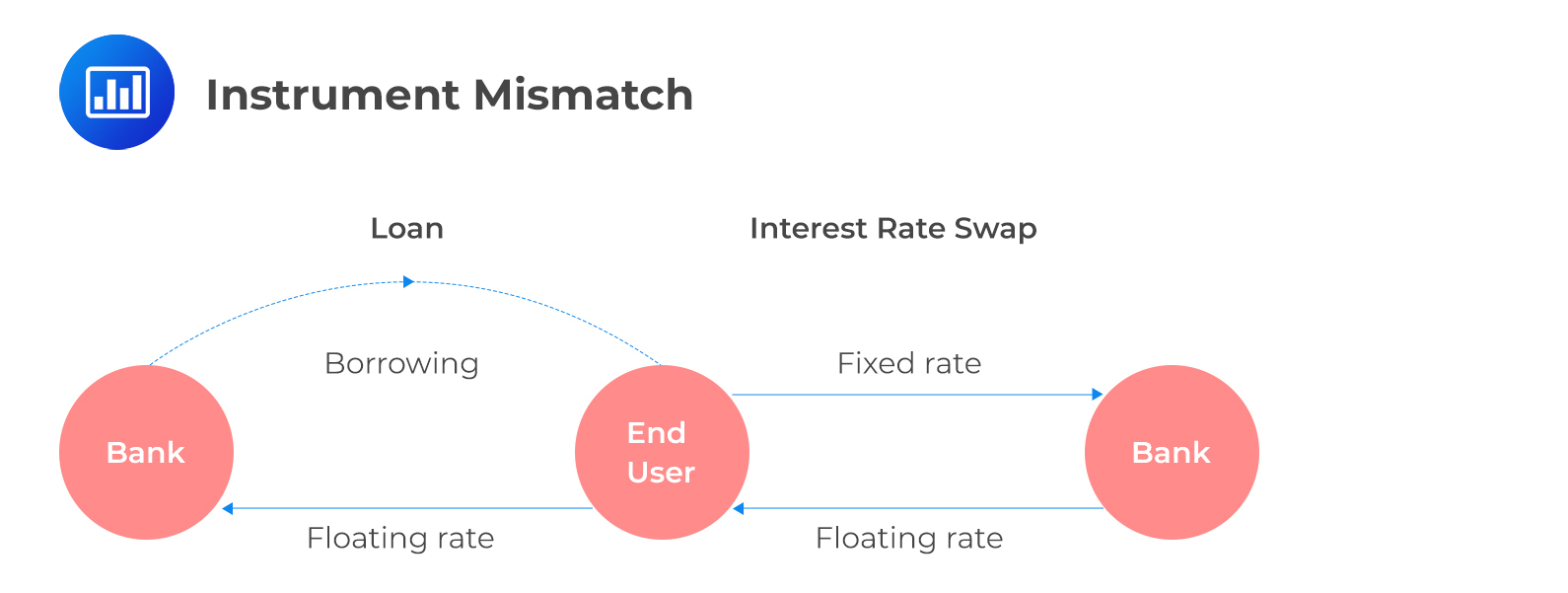

End users generally engage with a number of bank counterparties to distribute and manage their risk, based on the volume of their business and their risk appetite. However, their approach to hedging, often on a one-to-one basis, might limit the benefits of netting and lead to less favorable terms, especially in situations like unwinding transactions or dealing with defaults. For instance, hedging a floating rate loan with an interest rate swap to receive a fixed rate creates a direct link between the loan terms and the derivative. While this approach effectively hedges the interest rate risk, it also introduces complexities in terms of different accounting treatments and collateral requirements when compared to the bank’s perspective, where the loan is part of the ‘banking book’ and the swap is a ‘trading book’ item.

Banks

BanksBanks, on the other hand, aim to maintain a relatively flat book from a market risk perspective, meaning they strive to hedge their exposure comprehensively, often through a series of transactions in the interbank market or by directly offsetting a client transaction with another market participant. This approach allows banks to minimize their MTM volatility or market risk.

However, banks face a unique set of challenges, particularly regarding counterparty risk. While client transactions are often uncollateralized, the hedges banks engage in are usually bilaterally collateralized or fall under exchange-traded/centrally cleared mechanisms. This discrepancy introduces an asymmetry in collateral flows and can create situations where banks, despite having a neutralized overall MTM, are exposed to significant counterparty risk. If one party defaults, the bank remains exposed to the other party. Additionally, banks often deal with the directional hedging needs of clients, which can lead to significant collateral or margin requirements, especially in a falling interest rate environment.

In essence, while end users and banks engage in derivatives transactions with distinct objectives and strategies, both parties must navigate the intricacies of counterparty risk, collateral management, and market dynamics. The nature of their engagement in the derivatives market underscores the importance of understanding and managing the associated risks, particularly in the context of hedging strategies and the interconnectedness of market participants.

The International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) Master Agreement is pivotal in the over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives market. Established by the ISDA, a trade organization for OTC derivatives practitioners, this framework sets the standard for legal documentation, aiming to enhance efficiency and minimize counterparty risk. The Master Agreement, first introduced in 1985, is a testament to the rapid evolution of the OTC derivatives market, underscoring the necessity of a standardized legal framework to govern the complexities of these financial transactions.

The ISDA Master Agreement operates as a bilateral contract, encompassing terms and conditions to regulate OTC derivative transactions between two parties. It’s structured to bring multiple transactions under a single legal umbrella, thereby forming an indefinite, comprehensive contract. This agreement consists of:

The overarching goal of the ISDA Master Agreement is to eliminate legal uncertainties and furnish robust mechanisms for mitigating counterparty risk. The negotiation phase of the agreement can be extensive. However, once finalized, it facilitates seamless trading activities without necessitating frequent amendments or updates. Although the agreement typically adheres to English or New York law, it’s versatile enough to accommodate other legal jurisdictions, underscoring its global applicability.

Risk-Mitigating Features

The ISDA Master Agreement incorporates several features aimed at mitigating counterparty risk:

Default Events

The ISDA Master Agreement outlines specific scenarios that constitute events of default, triggering the termination and close-out of transactions. These events include:

Among these, the most encountered events of default are ‘failure to pay’ and ‘bankruptcy,’ typically subjected to predefined threshold amounts.

A sample ISDA Master Agreement can be found here:

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1355515/000127727706000388/exh43to8kpsa_lb20063.pdf

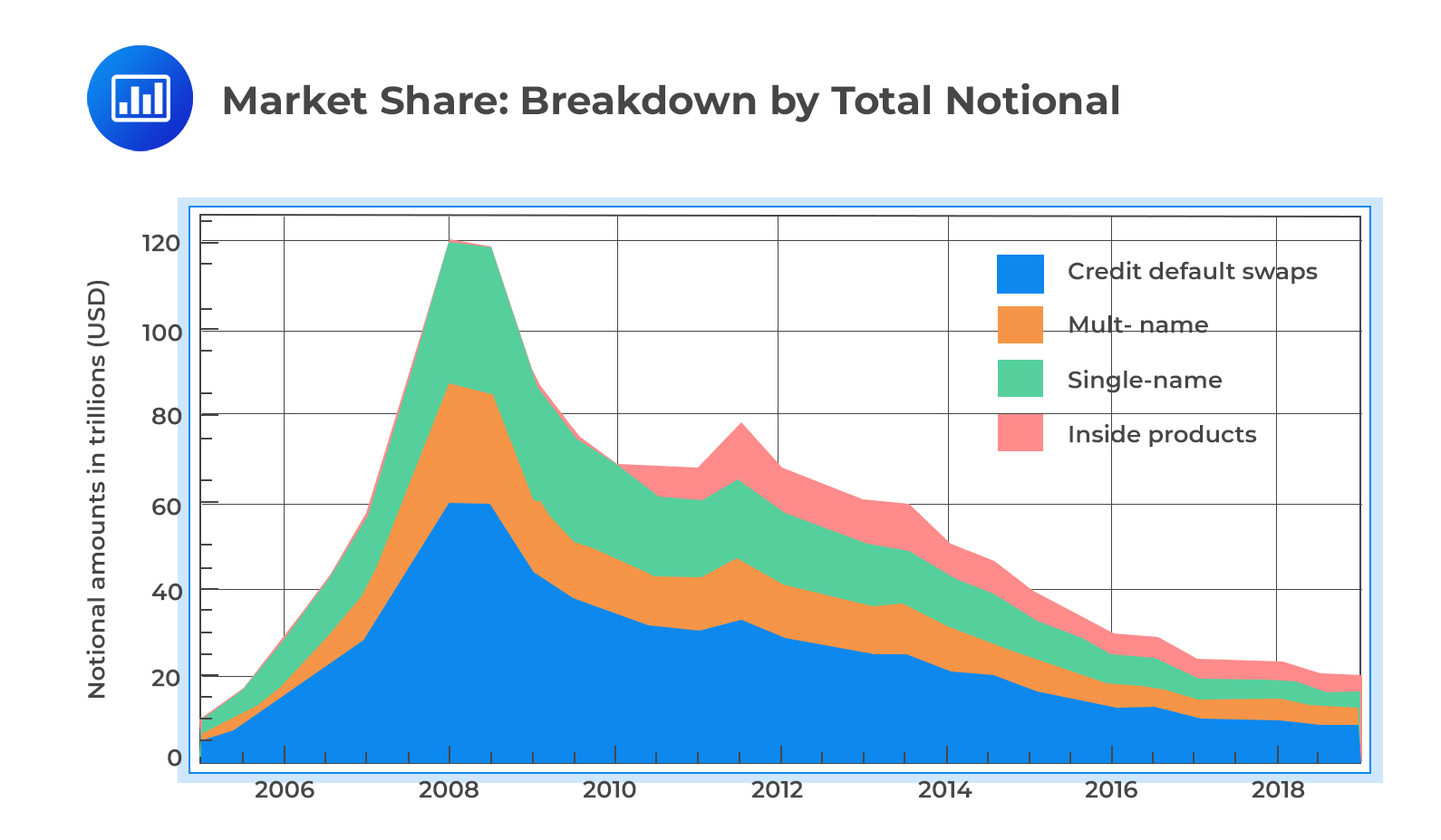

Credit derivatives have experienced rapid growth, particularly before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), mainly because they provide an efficient mechanism for transferring credit risk. Credit Default Swaps (CDS), the core instruments in this market, are notably simplistic but powerful tools that have significantly transformed how credit risk is traded. Their fundamental role is to hedge against the risk of default by a counterparty in other financial products. However, it’s crucial to recognize that while CDSs are instruments for hedging counterparty risk, they inherently contain counterparty risk within the contract itself.

Efficiency vs. Toxicity

Credit derivatives serve the dual purpose of being highly efficient in transferring credit risk while also having the potential to be counterproductive and toxic if not utilized correctly. This dichotomy emerges from their design and the inherent risks associated with their use. Proper usage of credit derivatives can lead to efficient risk management and financial stability. However, misuse or misunderstanding of these instruments can lead to significant financial distress, as evidenced in the periods leading up to the GFC.

Stalled Growth Post-GFC

The rampant growth of the credit derivatives market experienced a significant slowdown post-GFC. This shift reflects a growing awareness of the potential dangers associated with these instruments. The market’s realization of the risks, particularly those embedded in instruments like CDSs, has led to a more cautious approach towards credit derivatives.

Central Clearing and Counterparty Risk in the CDS Market

Central Clearing and Counterparty Risk in the CDS Market

A pivotal response to the risks identified with credit derivatives, especially CDSs, has been the move towards central clearing of standard Over-The-Counter (OTC) derivatives. This move aims to mitigate counterparty risk, a prominent concern associated with CDSs. Central clearing is perceived to offer a default remoteness, meaning it potentially reduces the likelihood of facing counterparty default. However, this approach’s effectiveness, especially concerning the handling of CDS products, is yet to be fully tested and proven. CDSs are notably more illiquid and carry higher risk compared to other products that are centrally cleared. Therefore, while central clearing is a significant step towards mitigating counterparty risk, its efficacy in handling the complexities and risks associated with credit derivatives, particularly CDSs, remains under scrutiny.

Derivatives, in their essence, are powerful and instrumental financial tools that have significantly contributed to the growth and efficiency of global financial markets. They are extensively used by a wide array of entities including corporations, investment managers, governments, insurers, energy firms, and financial institutions, indicating their pervasive presence in the modern financial landscape. However, despite their undeniable utility and the vast economic activities they facilitate, derivatives are not devoid of drawbacks. They have been at the center of financial turmoil and have been criticized for their potential to cause massive financial destabilization.

The Dual Nature of Derivatives

Derivatives are quintessentially double-edged swords. On one hand, they are indispensable tools for global economic activities, aiding thousands of companies in managing risks arising from their business and financial operations. They allow for risk management across more than 30 currencies worldwide, and most of the world’s largest 500 companies utilize derivatives to mitigate risk. However, not all derivatives transactions are socially beneficial. Some are utilized for arbitraging regulatory capital, tax requirements, or accounting rules. Misuse of derivatives has led to significant financial catastrophes, as evidenced by historical financial crises involving entities like Orange County, Proctor and Gamble, Barings Bank, Long-Term Capital Management, Enron, and Societe Generale.

Leverage: A Catalyst for Market Disturbances

A pivotal feature of derivatives is the significant leverage they provide. They often require a small or no upfront payment relative to the notional value of the contract, thereby offering substantial exposure without a corresponding investment. This leverage, while potentially beneficial, can amplify risks and has been instrumental in creating or accelerating major market disturbances.

Concentration of the OTC Market and Systemic Risk

The Over-The-Counter (OTC) derivatives market is dominated by a small number of dealers, creating a concentrated market structure. These dealers act as central counterparties to numerous end-users and manage their positions by actively trading with each other. This concentration was initially perceived as a stabilizing factor under the belief that these major dealers were too big to fail. However, this setup is now recognized as a source of significant systemic risk, where the potential failure of one institution can trigger a domino effect, destabilizing the entire financial system. The systemic risk is not only triggered by actual losses but can also arise from a mere perception of heightened losses.

Warren Buffett’s Criticism

In 2002, Warren Buffett famously described derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction,” highlighting their potential to cause widespread financial havoc. His criticisms were centered around four main points:

These insights from Buffett were particularly prescient in light of the events leading up to and following the 2007 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), underscoring some of the intrinsic risks in derivatives trading that were addressed in post-GFC regulations.

The Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008 stands as a monumental example of the challenges and complexities inherent in the derivatives market, particularly when a major counterparty defaults. This event sheds light on the intricate nature of derivatives clearing and the multifaceted risks involved in derivatives transactions.

The Rarity and Complexity of Major Derivatives Defaults

Defaults by major derivatives counterparties have been relatively rare, but the few instances, including Barings Bank and Long-Term Capital Management, underscore the inherent complexity in dealing with such events. Derivatives, by their nature, do not trade in secondary markets and lack an objectively defined valuation, making the resolution of a major derivatives default particularly challenging. The Lehman Brothers case exemplifies the difficulty created by derivatives, highlighting the multifaceted nature of financial risks, often a blend of market and credit risks among others.

The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers is a stark demonstration of the intricacies involved in settling derivative transactions when a major counterparty defaults:

The derivatives market, while offering numerous financial opportunities, is fraught with various types of risks. Here’s an in-depth look at the major types of risks as highlighted in the document:

Market risk arises from short-term movements of market variables. It can be:

Quantitative risk management techniques have been extensively applied to measure and manage market risk. Interestingly, market risk has also been a driving force behind the development of value-at-risk-type approaches for risk quantification. However, market risk isn’t standalone; it can form a component of counterparty risk if, for instance, offsetting contracts involve different counterparties. The imbalance of collateral agreements and central clearing arrangements can also lead to funding imbalances and associated costs.

Credit risk is the risk that a debtor may be unable or unwilling to make a payment or fulfill contractual obligations, commonly known as ‘default’. This risk varies depending on the jurisdiction involved and requires a full characterization of the default probability throughout the lifetime of the exposure, as well as the recovery value or the loss given default. Credit quality deterioration, such as a counterparty’s credit rating downgrade, can also lead to a marked-to-market (MTM) loss due to the increase in future default probability. This type of risk is particularly challenging to manage due to the necessity of understanding and characterizing the term structure of the counterparty’s creditworthiness.

Operational risk arises from people, systems, and internal and external events. It encompasses a range of issues:

Legal risk is often considered a subtype of operational risk. It’s the risk of losses due to the legal treatment assumed in contracts not being upheld. This could be due to various reasons, including incorrect documentation, fraud, mismanagement of contractual rights, or unexpected court decisions. Legal risk becomes particularly significant when it involves derivatives transactions with a defaulted counterparty, as the subjective valuation of these transactions can lead to significant disputes and financial losses.

Liquidity risk is manifested in two forms:

Counterparty risk is a combination of market and credit risk and is concerned with the likelihood of the counterparty to a derivative transaction defaulting on its obligations. It’s a critical risk in the derivatives market, especially given the complexity and global reach of these financial instruments. The mitigation of counterparty risk often involves collateralization, which, while reducing the probability of loss in case of a default, can introduce additional operational and liquidity risks.

It’s crucial to understand that these risk types are often interrelated. For instance, efforts to reduce counterparty risk through margining or collateralization can inadvertently increase funding liquidity risk due to the tight timescales often involved in these payments. This interconnectedness implies that managing one type of risk might inadvertently exacerbate another, necessitating a holistic and balanced approach to risk management in the derivatives markets.

Central clearing of OTC derivatives involves a process by which an intermediary, known as a Central Counterparty (CCP), stands between the two sides of a transaction to manage the credit risk associated with the trade. The CCP assumes the risk of default by one of the parties, thus providing a guarantee that the contract terms will be honored. Clearing takes place after a transaction is executed and before it is settled, incorporating the computation and potential netting of payment obligations between the firms engaged in the transaction.

Roles and Mandate of Central Counterparties (CCPs)

A CCP’s central role is risk management, which it accomplishes by becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer in a process known as ‘novation’. This ensures the integrity of the market and continued performance of trades even if one party defaults. CCPs are responsible for setting the rules and procedures for the transactions they oversee, including determining the requirements for collateral (margin) to guard against potential losses. The CCP’s primary mandate is thus to mitigate systemic risks associated with counterparty defaults and ensure market stability.

Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), CCPs have become crucial mechanisms to counter the systemic risk provoked by counterparty risk concerns. They were seen as financial ‘shock absorbers,’ effectively managing defaults to cause minimal market disruption. A key issue in defaults is the need to replace a large number of positions quickly in what can often be an illiquid market, which can lead to significant price movements and volatility. CCPs address these challenges by offering greater transparency and reducing risk via their margining practices.

Advantages of Central Counterparties (CCPs)

Disadvantages of Central Counterparties (CCPs)

While CCPs offer numerous benefits by centralizing and reducing counterparty risk, certain disadvantages are noteworthy:

The OTC derivatives market has undergone substantial evolution in its clearing practices and margin requirements, particularly in response to financial crises that highlighted systemic risks. Here’s an exhaustive analysis incorporating the aspects of CCP operations and their role in managing these risks:

Central Counterparties (CCPs) in OTC Derivatives Clearing

Central Counterparties (CCPs) mitigate the ‘domino effect’ in the derivatives market by acting as a financial shock absorber. In the event of a member’s default, CCPs swiftly terminate all financial relations with the defaulting party, aiming to prevent losses. This is achieved by replacing the defaulted counterparty with another clearing member, often through auctioning the defaulted member’s positions among other members, ensuring continuity for surviving members.

CCPs introduce loss mutualization, where losses from one counterparty are dispersed across all clearing members, preventing adverse consequences on a smaller number of counterparties. They facilitate orderly close-outs by auctioning the defaulter’s obligations, with multilateral netting to minimize price impacts and market volatility. Additionally, CCPs can orderly transfer client positions from financially distressed members, enhancing market stability.

Financial Resources and Risk Management by CCPs

CCPs are responsible for setting standards for their clearing members, closing out positions of a defaulting clearing member, and maintaining financial resources to cover losses in the event of a default. These resources include:

CCPs have plans for extreme situations when all their financial resources are depleted, including additional calls to the default fund, variation margin haircutting, and selective tear-up of positions:

Not all entities, particularly banks and most end-users of OTC derivatives (like pension funds), become direct members of CCPs. Instead, they access CCP services through a clearing member due to operational and liquidity requirements. Regular participation in ‘fire drills’ and bidding in CCP auctions are among the reasons institutions may choose not to become direct clearing members at a given CCP.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the G20 leaders mandated the development of standards for margining for non-centrally cleared OTC derivatives. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and the International Organization for Securities Commission (IOSCO), along with other relevant organizations, were tasked to develop these standards. The objective was to introduce margin requirements that would mimic those under central clearing, thus providing a strong incentive for market participants to move as many OTC derivatives to central clearing as possible. These regulations aimed to reduce systemic risk and prevent a domino effect in the financial markets by ensuring that unexpected losses caused by the failure of one or more counterparties would be shared (‘loss mutualization’) amongst all members of the CCP, rather than being concentrated within a smaller number of institutions that may be heavily exposed to the failing counterparty.

The Working Group on Margin Requirements (WGMR) was established to develop the framework for these bilateral margin requirements. These requirements are intended to mitigate concerns faced by institutions and prevent any extreme actions by those institutions that could worsen a crisis.

Key achievements of the WGMR with respect to developing margin requirements for non-centrally cleared derivatives include:

Central Counterparties (CCPs) played a significant and stabilizing role in the financial markets during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), particularly in the Over-The-Counter (OTC) derivatives market. Notably, the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy, a major event of the crisis, did not cause substantial problems for CCPs like LCH.Clearnet and Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC). These organizations acted promptly, suspending insolvent Lehman entities from trading, thereby preventing the accrual of further risk. Concurrently, solvent Lehman entities were identified and allowed to continue trading. The CCPs efficiently facilitated the transfer of solvent client accounts to other clearing members, providing stability and safety to Lehman’s counterparties and clients in cleared markets and mitigating potential knock-on or systemic effects due to the bankruptcy of a major OTC derivatives player.

A prime example of CCP effectiveness during the GFC is evident in LCH.Clearnet’s London-based SwapClear service. SwapClear provided interest rate swap central clearing for 20 large banks, including Lehman Brothers. The service managed a total portfolio exceeding $100 trillion notional across 14 currencies, representing nearly half of the global interest rate swap market at the time. Despite previous experiences with defaults (e.g., Drexel Burnham Lambert in 1990 and Barings in 1995), the Lehman failure marked the largest default in CCP history.

Lehman Brothers Special Financing Inc. (LBSF), a significant player in SwapClear, held a $9 trillion OTC portfolio consisting of tens of thousands of trades. On 15th September 2008, LBSF defaulted on margin payments, leading to its declaration as a defaulter within hours. The primary objective for LCH.Clearnet was to swiftly and efficiently close out LBSF’s extensive OTC portfolio without inducing significant losses or knock-on effects. A substantial amount of initial margin (around $2 billion) held from Lehman for such contingencies was crucial in achieving this goal.

The CCP’s response to the Lehman default was systematic and effective:

The handling of the Lehman default by LCH.Clearnet was considered a success, requiring only about a third of the initial margin, with the remainder returned to Lehman administrators. However, the process was not devoid of challenges. For instance, due to poor record-keeping by Lehman and certain legal stipulations in the UK, some clients’ margins were returned to the administrator and frozen for an extended period. Access to Lehman’s offices was also initially restricted.

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), also known as Special Purpose Entities (SPEs), are legal entities, such as a company or limited partnership, established for a specific purpose. Often utilized in the Over-The-Counter (OTC) derivatives market, SPVs serve as a tool to isolate and manage financial risk. The primary function of an SPV is to segregate certain assets and liabilities within a larger entity, typically to protect these assets from the entity’s broader financial risk. Here’s a detailed look into the role, mechanism, and limitations of SPVs:

Role and Mechanism

Limitations and Considerations

Derivatives Product Companies (DPCs) emerged as a response to the inherent vulnerabilities of the bilaterally-cleared, dealer-dominated OTC market to counterparty risk. These entities, often triple-A-rated, were formed by banks as bankruptcy-remote subsidiaries of major dealers. Unlike Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), DPCs are separately capitalized to achieve their high credit rating. The initial purpose of a DPC was to offer a high-credit-quality counterparty for OTC derivatives, especially for long-dated ones, to counterparties with less than triple-A credit quality.

DPCs aimed to neutralize market risk, mainly by maintaining a market risk-neutral position through offsetting contracts, often with the DPC’s parent company. They were supported by parent companies but were designed to be bankruptcy remote from these parents to secure a better rating. This structure was supposed to ensure that if the parent defaulted, the DPC would either be transferred to another well-capitalized institution or be terminated with trades settled at mid-market. Moreover, DPCs were governed by stringent credit risk management and operational guidelines, including restrictions on counterparty credit quality, position limits, and daily mark-to-market (MTM) and margining/collateralization.

DPCs also aimed to provide security by defining an orderly workout process in case of their failure, triggered by events such as a rating downgrade of the parent company. The ‘pre-packaged bankruptcy’ approach of DPCs was intended to offer a simpler and less likely bankruptcy process compared to a standard bankruptcy in the OTC derivatives market.

Challenges and Limitations

While DPCs were created to facilitate trading and mitigate counterparty risk, their effectiveness in isolating risk has been questioned. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) severely impacted the world of DPCs, questioning the real counterparty risk mitigation they offered. The collapse and subsequent rescue of parent companies like Bear Stearns led to the winding down of their DPCs, illustrating that the fate of a DPC is significantly tied to that of its parent, contradicting the notion of being ‘bankruptcy remote’. This interdependence led to skepticism regarding the autonomy of DPCs and resulted in rating agencies withdrawing ratings from these entities.

Furthermore, DPCs illustrate the complex transformation of counterparty risk into other forms of financial risks, such as legal, market, and operational risks. This transformation questions the effectiveness of DPCs in truly mitigating counterparty risk, as the mitigated risk in one area might lead to increased risk in another. Therefore, the rating and the perceived credit quality of a DPC should be carefully considered in the context of its parent company’s rating and financial stability.

Monoline insurance companies, including entities like AIG, initially emerged as financial guarantee companies possessing robust credit ratings. These firms were pivotal in providing ‘credit wraps,’ which are essentially financial guarantees. The primary role of these credit wraps was to guarantee municipal bonds and other types of public finance debt, ensuring that investors would receive scheduled payments even if the issuer defaulted.

Over time, monolines ventured beyond their traditional sphere, providing credit wraps in other areas, notably in the single-name Credit Default Swaps (CDS) and structured finance markets. This strategic move was driven by the intent to diversify their services and harness better returns. However, the expansion into these more complex and risk-prone areas eventually led to significant challenges, especially during the financial crisis of 2007-2008.

Limitations and Risks

Credit Derivatives Product Companies (CDPCs) are entities that deal primarily in the credit derivatives market. Similar to monoline insurers, CDPCs are often highly leveraged and play a significant role in the financial markets by providing credit protection to other financial institutions. However, they have their own set of characteristics and limitations that are important to understand:

Characteristics and Role of CDPCs

Limitations and Challenges during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)

The modeling of derivatives risk is a core function of financial risk management and has undergone significant evolution over the past two decades. The development of quantitative approaches, such as value-at-risk (VaR), has been pivotal in enabling institutions to summarize complex risk factors efficiently. These models allow for comparisons between different trades and aid in making rapid decisions in fluid financial markets.

Approaches in Derivatives Risk Modeling

Value-at-Risk (VaR)

VaR has been instrumental in modeling market risks and has been extended across financial areas to summarize risks succinctly. It provides a quantile of the loss distribution a portfolio is likely to experience over a given time frame, within a certain confidence level, without making distributional assumptions.

Expected Shortfall (ES)

ES, also known as conditional VaR (CVaR), is an extension of VaR that captures the mean of losses that exceed the VaR threshold, addressing tail risks ignored by VaR. Unlike VaR, ES takes into account the magnitude of losses in the tail of the distribution, making it a more comprehensive measure of risk.

Historical Simulation and Backtesting

These methods incorporate historical market data to simulate current portfolio behavior, providing a range of outcomes. Historical simulation is straightforward to apply to VaR and ES because of short time horizons, typically ten days. Regulators permit scaling one-day VaR to ten days using the square root of the time rule. Backtesting further validates the model’s predictions by comparing them with actual outcomes.

Counterparty Risk Metrics

Counterparty risk modeling, including metrics like Potential Future Exposure (PFE), is crucial for managing credit risks over the longer term. However, counterparty risk involves assessing risks many years into the future, which introduces additional complexity as the methods need to be reliable over extended periods.

Challenges in Modeling Derivatives Risk

Practice Question

In the derivatives market, a financial institution is evaluating the risks associated with a new swap contract. The contract’s value will change over time based on market conditions and the performance of an underlying asset. The institution is particularly concerned about the risk of the counterparty defaulting on the contract. Which type of risk is the institution primarily concerned about in this scenario?

- Market risk

- Operational risk

- Liquidity risk

- Counterparty credit risk

The correct answer is D.

Counterparty credit risk in derivatives arises from the possibility of a counterparty failing to meet its contractual obligations, particularly in the event of insolvency. In a swap contract, as in other derivatives, this risk is significant because the value of the contract depends on the underlying asset and market conditions. If the counterparty defaults, the institution faces the risk of loss based on the derivative’s market value at that time. This risk is a combination of credit and market risks, making it distinct and critical in derivatives transactions.

A is incorrect because market risk refers to the risk of losses in on- and off-balance sheet positions arising from movements in market prices. While market conditions affect the value of the derivative, the institution’s primary concern here is the counterparty’s ability to fulfill its obligations, not the market fluctuations per se.

B is incorrect because operational risk involves the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, systems, or from external events. This risk category is not directly related to the counterparty’s creditworthiness in a derivative contract.

C is incorrect because liquidity risk pertains to the risk that a firm will not be able to meet its financial obligations as they fall due without incurring unacceptable losses. While important, it is not the central concern in the context of counterparty default in a derivative contract.

Things to Remember

- Counterparty credit risk in derivatives is dynamic, changing over the life of the contract in response to market conditions and the performance of the underlying asset.

- This risk is managed through various methods, including clearing processes and collateral requirements, to mitigate the potential impact of a counterparty’s default.

- Understanding the combination of credit and market risks in counterparty credit risk is crucial for effective risk management in derivatives transactions.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.