Covered Call Position

Introduction to and Objectives of the Covered Call A covered call strategy has... Read More

The Private Markets Pathway learning modules focus on the realm of private investments. These investments can be in the form of company debt or equity, real estate, or infrastructure. A key characteristic of these investments is their illiquidity, meaning they cannot be easily sold or exchanged for cash without a substantial loss in value. These investments are typically held for multiyear periods and span across various phases of a company’s life-cycle or project development. For instance, a private equity firm might invest in a start-up company, providing it with the necessary capital to grow and develop over several years.

While many situations may fall into the category of financial dislocation, it is crucial to distinguish between financial distress and other event-driven opportunities. Financial distress refers to situations where a company is unable to meet or pay its financial obligations. For instance, a company might be unable to pay its debt due to poor cash flow. On the other hand, event-driven opportunities refer to situations that are driven by specific events that have the potential to significantly impact the value of an investment. For example, a merger or acquisition could significantly increase the value of a company’s stock.

Financial distress is a term that describes a situation where a company or individual is unable to meet their financial obligations, such as loan repayments or bond interest payments. This is often referred to as distressed debt . Financial distress can be triggered by several events such as failure to pay a contractual debt obligation on time, violation of a financial covenant in a bond indenture or loan agreement, or a situation where the market value of a firm’s assets falls below that of its fixed obligations when valued as a going concern. For instance, a company like Toys “R” Us, which filed for bankruptcy in 2017, was in financial distress because it was unable to meet its debt obligations.

The distribution of a firm’s value between shareholders and debtholders depends on the financial health and solvency of the firm. Here’s a clearer explanation:

Debtholders as Residual Claimants: In scenarios where firms cannot fulfill their debt obligations, debtholders may end up being the ones to claim any remaining net assets of the firm. A notable instance of this was during the 2008 financial crisis with Lehman Brothers, where the company’s failure to meet its debt commitments led to debtholders claiming its residual assets.

Solvent Firms (V > D): When a firm is solvent, meaning its total value (V) is greater than its debt (D), debtholders are paid back in full. Any value that remains after settling debts goes to the shareholders. An example of this scenario was General Motors during the 2009 financial crisis, where, after receiving government aid, the company was solvent enough to satisfy its debt obligations, leaving residual value for its shareholders.

Insolvent Firms (V < D): In cases where the firm is insolvent, with total liabilities surpassing the market value of its assets, debtholders receive a portion of their promised interest and principal, often less than the full amount, while shareholders are left with nothing. This was dramatically illustrated by the collapse of Enron in 2001, where the company’s insolvency led to total losses for its shareholders.

A distressed investor might seek to capitalize on the expected outcome by either purchasing the bonds of an issuer trading at a significant discount to par in anticipation of being paid in full or receiving a higher discounted price or selling short the stock of an issuer that is expected to become insolvent. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, some investors bought distressed mortgage-backed securities at a discount, betting that they would recover in value. Investors may seek a more active role in restructuring as a significant minority or controlling investor or use the process to acquire and eventually resell an entire company. This is a common strategy used by private equity firms.

Financial distress in firms can arise from a myriad of factors, ranging from broad economic downturns to specific industry or company-level challenges. The causes are as follows:

Economic Downturns: General economic downturns can lead to reduced operating and financial performance across many sectors. A prime example is the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly impacted the travel and hospitality industry, pushing numerous companies into financial distress due to reduced consumer demand and operational restrictions.

High-Yield Issuer Defaults: Companies that issue high-yield (or sub-investment-grade) bonds face a higher likelihood of defaulting on their obligations, especially during economic or sector-specific downturns. For instance, the 2014 oil price crash led to a wave of defaults among high-yield bond issuers in the energy sector due to plummeting oil prices and reduced profitability.

Industry-Specific Factors: Even in times of overall economic stability, specific industries can undergo challenges that lead to financial distress among firms within those sectors. For example, rapid technological changes can render existing products or services obsolete, impacting companies in the technology sector.

Company-Specific Risk Factors: Financial distress can also stem from individual company issues, such as a deteriorating competitive position, market risks related to the firm’s products, execution risks, or high operating leverage. Kodak’s financial distress, brought on by its failure to adapt to digital photography, illustrates how company-specific factors can lead to significant financial challenges.

One measure of investor loss in a default scenario is the credit loss rate, the realized percentage of par value lost to default for bonds, equal to the bonds’ default rate multiplied by the loss severity. For example, if a bond has a default rate of 2% and a loss severity of 50%, the credit loss rate would be 1%.

Credit risk is a significant concern in distressed investments. It is quantified using the Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA) framework. The CVA measures the present value of expected loss (EL), which is the product of the probability of default (POD) and loss given default (LGD). The EL can be calculated as:

$$ \text{EL} = \text{LGD} \times \text{POD} $$

For instance, if a company like Toys “R” Us, which filed for bankruptcy in 2017, had a high probability of default, the expected loss would rise to nearly equal the loss given default. The price of the underlying debt (as a percentage of face value) would then approach the expected recovery rate in a default scenario. To identify sources of credit risk, analysts differentiate between short-term issuer liquidity and longer-term solvency issues. Liquidity refers to the ability to convert a firm’s resources into cash to cover its immediate obligations, while solvency assesses an issuer’s cash flow generation potential over multiple periods to meet interest and principal payments.

Debt and equity instruments of issuers facing financial distress often face limited liquidity as price volatility increases. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, many market participants were forced to sell their investments in distressed debt or equity securities due to their investment policies. Public equities that fail to meet minimum exchange price requirements are often delisted as a firm approaches default.

Operational risk is another significant concern for firms facing financial distress. For instance, a company like Kodak, which filed for bankruptcy in 2012, may lose employees, customers, or suppliers unwilling to bear the greater risk of non-payment or liquidation while the firm restructures its debt or pursues bankruptcy.

Legal risk involves the costs and uncertainty associated with financial distress, including creditor disputes and bankruptcy proceedings. As both the risks and costs associated with bankruptcy and other forms of litigation reduce the assets available to settle claims, distressed debt investors must weigh these costs against the potential benefits of pursuing such legal action.

Sovereign borrowers can face financial distress due to factors like excessive fiscal deficits, rigid monetary and exchange rate policies, and adverse economic conditions. A notable case is Greece’s 2010 financial crisis, triggered by such fiscal and policy mismanagement.

Developing market sovereigns are particularly vulnerable due to limited economic diversification, fewer trade partners, and underdeveloped financial markets. Their often restrictive and non-convertible exchange rate regimes exacerbate the effects of economic shocks, heightening distress risks.

Distressed corporate issuers typically seek to restructure debt through legal bankruptcy proceedings, allowing them to continue operations while addressing financial obligations.

For sovereign issuers, the principle of sovereign immunity limits lenders’ legal options to enforce debt repayment, leading usually to debt restructuring rather than liquidation.

Fiscal deficits and falling tax revenues often distress sovereign bonds denominated in domestic currencies, while those in foreign currencies may suffer from external pressures like domestic currency depreciation.

Investors in distressed sovereign debt may face significant losses, with defaults typically resolved through restructuring plans that might include austerity measures and financial institution interventions (e.g., IMF).

Such restructuring often results in losses for debt investors through terms like payment deferrals, extended terms, and other concessions.

Investors in corporate or sovereign distressed debt encounter reputational risks that may arise from actions perceived as harmful to workers, communities, and the environment. This risk is significant for public sector investors with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals, such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds, due to the potential adverse impacts of their investment decisions.

Investing in the distressed debt of heavily indebted poor countries (HIPCs) can be particularly contentious. These countries, identified by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank for their high poverty levels and debt burdens, present a moral dilemma. Investors in HIPCs’ debt might be seen as exploiting these nations’ financial hardships, risking reputational damage.

Public sector investors must be wary of the reputational risks involved in distressed debt investing, especially when such investments could have negative social and environmental consequences. An illustrative scenario is a pension fund that pressures a defaulting developing country to liquidate assets, potentially causing widespread harm and attracting criticism for exploiting the crisis.

Reputational risk extends beyond negative publicity; it can lead to tangible financial losses. For instance, a sovereign wealth fund experiencing reputational damage due to controversial investment strategies may face divestment, resulting in significant capital depletion.

It is crucial for investors, particularly those with ESG mandates, to consider the broader implications of their distressed debt investments. This includes assessing not only the financial returns but also the potential reputational risks and their impact on society and the environment.

Event-driven investment strategies focus on unique business activities and corporate actions that present significant opportunities. These include mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, and more. Such events can drastically alter a company’s valuation, offering savvy investors a chance to capitalize on these changes.

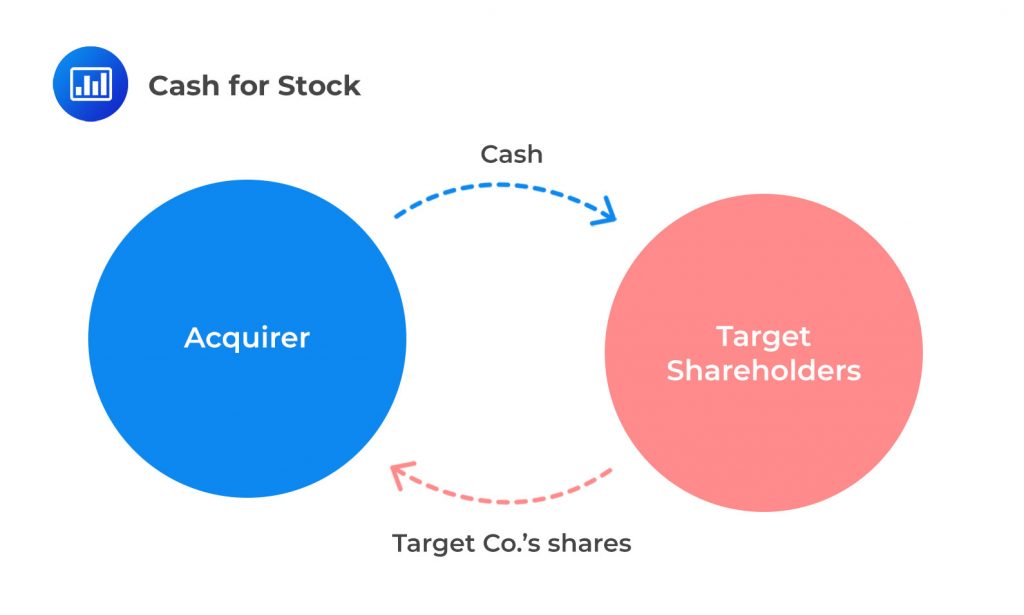

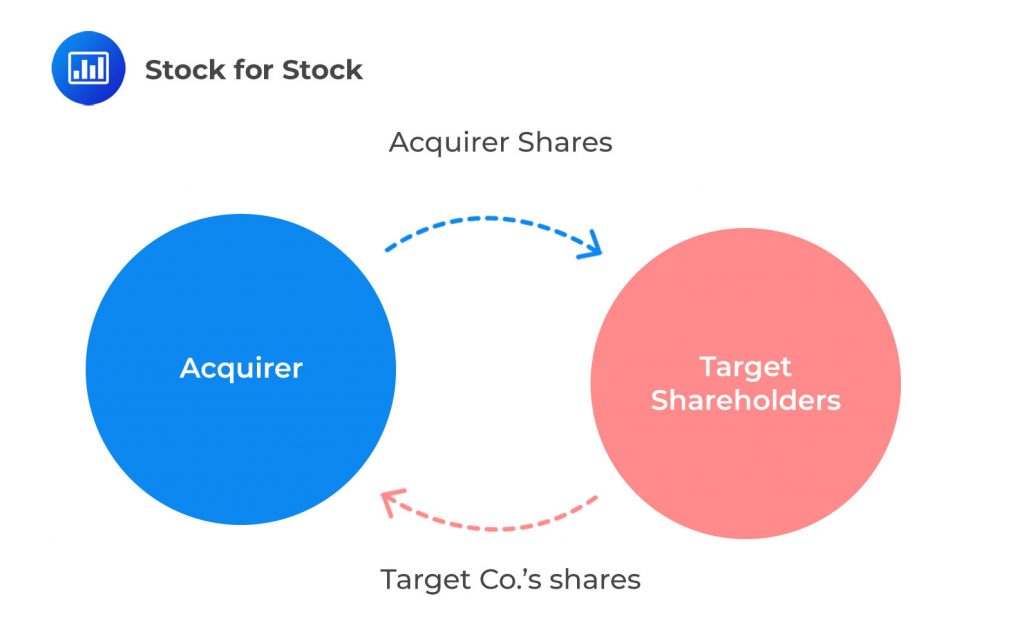

M&A activities are prime examples of event-driven opportunities. A notable case is Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019, which created a merger arbitrage scenario. Investors aim to exploit price discrepancies arising from the deal’s announcement, betting on the successful closure of the merger and the final transaction terms.

This strategy involves leveraging differences between the acquisition price and the market price post-announcement. While offering potential returns if the deal concludes as planned, it also carries the risk of the transaction failing due to various factors like regulatory hurdles or financial issues.

Acquisitions can lead to debt-related arbitrage opportunities, especially when the acquiring company takes on the target’s debt. Strategies may involve capitalizing on change of control clauses or bond tender offers, where bonds are repurchased at a premium.

Investors might engage in capital structure arbitrage, leveraging mispricings within a company’s debt and equity. Convertible arbitrage, focusing on convertible bonds, allows investors to benefit from mispricing of risk components such as credit risk and equity volatility.

Both merger and convertible arbitrage strategies often employ borrowed funds to enhance returns. This leveraged approach, while increasing potential profits, also amplifies risks, underscoring the need for careful risk management in event-driven investing.

Practice Questions

Question 1: In private investments, different strategies are employed to target returns. One such strategy is investing in special situations, which often occur over a shorter time frame compared to other private market strategies. The value creation process in these situations is unique as it involves discrete events that significantly impact investment value. What special situations refer to in the context of private investments?

- Investments in company debt or equity, real estate, or infrastructure.

- Investments in stressed, distressed, or event-driven opportunities.

- Investments in situations where market prices are misaligned due to various factors.

Answer: Choice B is correct.

Special situations refer to investments in stressed, distressed, or event-driven opportunities in the context of private investments. These situations often arise due to specific events such as mergers, acquisitions, spin-offs, bankruptcy, restructurings, or other corporate actions that can significantly impact the value of an investment. The goal of special situations investing is to capitalize on the mispricing that often occurs in these situations due to the uncertainty and complexity involved. Investors in special situations aim to profit from the resolution of these situations, which often involves a change in the capital structure of the company or a change in the company’s strategic direction. This strategy requires a deep understanding of the specific situation and the ability to assess the potential outcomes and their impact on the value of the investment.

Choice A is incorrect. While investments in company debt or equity, real estate, or infrastructure can be part of a private investment strategy, they do not specifically refer to special situations. These types of investments can be part of any private investment strategy, not just special situations.

Choice C is incorrect. While investments in situations where market prices are misaligned due to various factors can be part of a special situations strategy, this definition is too broad and does not capture the unique characteristics of special situations. Special situations involve specific events that significantly impact the value of an investment, not just any situation where market prices are misaligned.

Question 2: An investor is considering investing in a company that is trading at a significant discount to par due to financial distress. The investor believes that the company will be able to meet its future interest and principal payments. What strategy might the investor employ to capitalize on this expected outcome?

- The investor might sell short the stock of the issuer.

- The investor might purchase the bonds of the issuer in anticipation of being paid in full or receiving a higher discounted price.

- The investor might seek a more active role in restructuring as a significant minority or controlling investor.

Answer: Choice B is correct.

If an investor believes that a company, which is currently in financial distress and trading at a significant discount to par, will be able to meet its future interest and principal payments, the most direct strategy to capitalize on this expected outcome would be to purchase the bonds of the issuer. This is because the bonds of a company in financial distress are likely to be trading at a significant discount to their face value. If the company is able to recover and meet its future obligations, the value of these bonds will increase, providing a significant return to the investor. This strategy is based on the principle of buying low and selling high, and it requires a thorough understanding of the company’s financial situation and prospects for recovery.

Choice A is incorrect. Selling short the stock of the issuer would be a strategy to capitalize on the expected decline in the company’s stock price, not its recovery. Short selling involves borrowing shares of a stock and selling them in the market with the expectation that the stock price will fall, allowing the short seller to buy back the shares at a lower price and return them to the lender, pocketing the difference. If the investor believes that the company will be able to meet its future obligations, short selling would not be an appropriate strategy.

Choice C is incorrect. Seeking a more active role in restructuring as a significant minority or controlling investor is a strategy that involves a high level of involvement and risk. It would require the investor to take on a significant role in the company’s management and decision-making process, which may not be feasible or desirable for all investors. Moreover, this strategy would only be appropriate if the investor believes that the company’s current management is not capable of leading the company out of financial distress, which is not the scenario presented in the question.

Private Markets Pathway Volume 2: Learning Module 5: Private Special Situations; LOS 5(a): Discuss the characteristics and risks of special investment situations

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.