Managing Nondeposit Liabilities

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Differentiate the various sources... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

Compare different types of credit derivatives, explain their application, and describe their advantages.

Lending is undoubtedly one of the most profitable investment avenues for banks. Traditionally, banks take short-term deposits and pool them together to provide long-term loans. However, these loans introduce credit risk – the possibility that the funds disbursed may not be recovered following an event of default by the borrower. There are several ways used by banks to deal with credit risk exposure. Banks can

Accept the risk, where the bank simply provides loans and takes no further action

Avoid the risk, which means the bank turns down credit applications

Reduce the risk by taking measures that eliminate at least part of the exposure, for example, by adopting a rigorous screening process at the application stage

Transfer the risk to some other entity or person (collectively referred to as the counterparty)

In this chapter, we will extensively look at various methods used by banks to transfer credit risk exposure.

Risk transfer practices among banks gained momentum towards the late 20th century. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan acknowledged that credit derivatives and securitizations played a pivotal role in enabling the United States banking system to weather the 2001-2002 economic slowdown with minimal impact. Key instruments during that period included credit default swaps (CDS), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs).

However, following the 2007-2009 financial crisis, credit derivatives faced significant criticism. It became evident that the issue lay not in the instruments themselves but in their misuse. While some of these instruments faded from the market in the aftermath, others, such as the CDS and CLO markets, remained strong and continue to be widely utilized by banks for managing and transferring credit risk. Complex instruments like collateralized debt obligations squared (CDOs-squared) and single-tranche CDOs are unlikely to reemerge. In recent years, innovative credit risk transfer mechanisms have also been developed.

Credit derivatives are financial instruments that transfer the credit risk of an underlying portfolio of securities from one party to another party without transferring the underlying portfolio. They are usually privately held, negotiable contracts between two parties. A credit derivative allows the creditor to transfer the risk of the debtor’s default to a third party.

Credit derivatives are over-the-counter: instruments, meaning they are non-standardized, and the Securities and Exchange Commission regulations do not bound their trading.

The main types of credit derivatives include:

In a CDS, one party makes payments to the other and receives in return the promise of compensation if a third party defaults.

Example:

Suppose Bank A buys a bond issued by ABC Company. In order to hedge the default of ABC Company, Bank A could buy a credit default swap (CDS) from insurance company X. The bank keeps paying the insurance company fixed periodic payments (premiums) in exchange for default protection.

Debt securities often have longer terms to maturity, sometimes as much as 30 years. Consequently, it is difficult for the creditor to develop reliable credit risk estimates over such a long investment period. For this reason, over the years, credit default swaps have become a popular risk management tool. As of June 2018, for example, a report by the U.S. Comptroller of the Currency office placed the size of the entire credit derivatives market at $4.2 trillion, of which credit default swaps accounted for $3.68 trillion (approx. 88%).

Like other derivatives, the payoff of a CDS is contingent upon the performance of an underlying instrument. The most common underlying instruments include corporate bonds, emerging market bonds, municipal bonds, and mortgage-backed securities.

The value of a CDS rises and falls as opinions change about the likelihood of default. An actual event of default might never occur. A default event can be difficult to define when dealing with CDSs. Although bankruptcy is widely seen as the “de facto” default, there are companies that declare bankruptcy and yet proceed to pay all of their debts. Furthermore, events that fall short of default can also cause damage to the creditor. These events include late payments or payments made in a form different from what was promised. Trying to determine the exact extent of damage to the creditor when some of these events happen can be difficult to determine. CDSs are designed to protect creditors against such credit events.

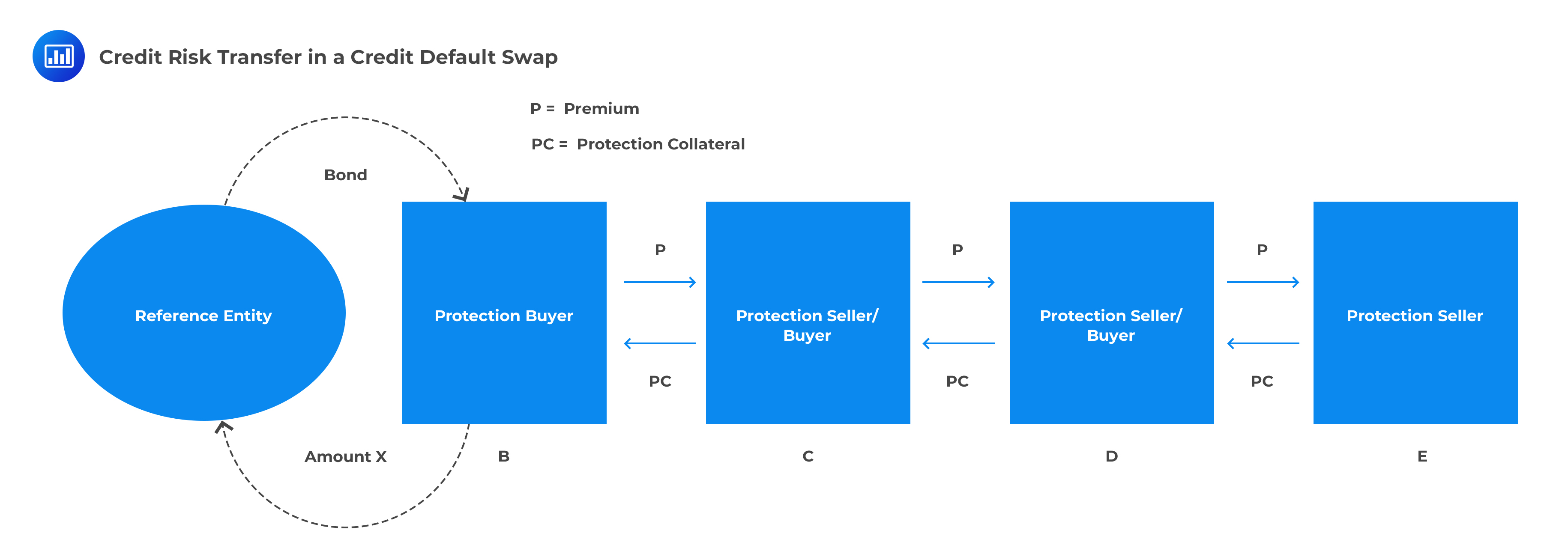

Example: Assume that we have five parties – A, B, C, D, and E. We assume that party B buys protection from party C for the loan made to party A, but C also transfers this risk to party D, and D does the same and buys protection from monoline insurer E. In this scenario, there are three individual agreements made, but economically, only the last buyer (the monoline insurer) bears the ultimate risk. Most important, the gross notional amount is inflated three times more than the aggregate net exposure.

Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are structured products created by banks to offload risk. The first step entails forming diversified portfolios of mortgages, corporate bonds, and various other assets. These portfolios are then sliced into different tranches and sold to investor groups with different risk appetites.

The safest tranche is also known as the senior tranche. It offers the lowest interest rate, but it is the first to receive cash flows from the underlying asset portfolio. The middle tranche offers a slightly higher interest rate and ranks just below the senior tranche. Thus, it takes the second spot during cash flow distribution. The most junior tranche, also called the equity tranche, offers the highest interest rate but ranks during cash flow distribution. It is also the first tranche to absorb any loss that may be incurred. The amount available for distribution to the equity (junior) tranche is whatever is left from the two other tranches, the m management fees. These fees can range from 0.5% to 1.5% annually.

Investors in these tranches can protect themselves from default by purchasing credit default swaps. The CDS guarantees a pre-specified compensation if a given tranche defaults. In turn, the investors must make regular payments to the credit protection seller (writer of the CDS).

Each tranche is assigned its credit rating, except the equity tranche. For instance, the senior tranche is constructed to receive an AAA rating. Highly rated tranches are sold to investors, but the junior-ranking ones may end up being held by the issuing bank. That way, the bank has an incentive to monitor the underlying loans.

Let us assume there is a $100 million collateral portfolio that is composed of debt at 6%. To pay for this collateral, the CDO is divided into three tranches:

In this scenario, the $85m of Class A would pay out $4.25m (= $85m x 5.0%) in interest each year, Class B pays out $0.9 ($10m x 9.0%). Of the remaining $0.85m ($6m – $4.25m – $0.9m), $0.2m is used to pay for fees, leaving the equity holders with a return of 13% ($0.65m/$5m).

When used responsibly, CDOs can be excellent financial tools that can increase the availability and flow of credit in the economy. By selling CDOs, banks can free up more funds that can be lent to other customers.

A collateralized loan obligation is similar to a collateralized debt obligation, except that the underlying debt is a company loan instead of a mortgage. The investor receives scheduled debt payments from the underlying loans, bearing most of the risk if borrowers default.

As with CDOs, CLOs use a waterfall structure to distribute revenue from the underlying assets. The structure dictates the priority of payments when the underlying loan payments are made. It also indicates the risk associated with the investment since investors who are paid last (equity holders) have a higher risk of default from the underlying loans.

CLOs have the same set of advantages and disadvantages as CDOs.

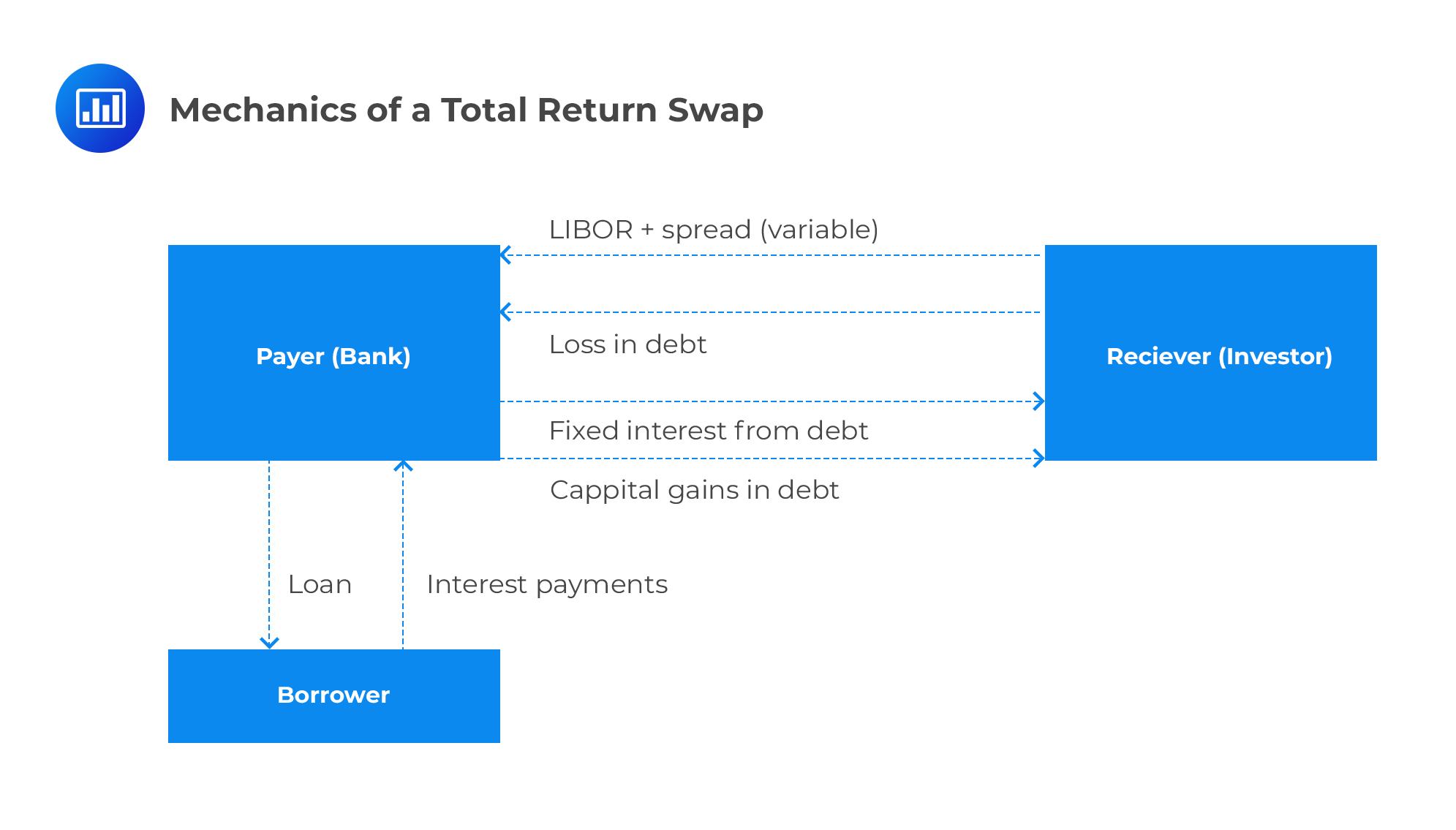

A total return swap is a credit derivative that enables two parties to exchange both the credit and market risks. In a total return swap, one party, the payer, can confidently remove all the economic exposure of the asset without having to sell it. The receiver of a total return swap, on the other hand, can access the economic exposure of the asset without having to buy it.

For example, consider a bank with significant (but risky) assets in the form of loans in its books. Such a bank may want to reduce its economic exposure concerning some of its loans while still retaining a direct relationship with its customer base. Therefore, the bank can enter into a total return swap with a counterparty that desires to gain economic exposure to the loan market. What happens is that the bank (payer) pays the interest income and capital gains coming from its customer base to these investors. In return, the counterparty (receiver) pays a variable interest rate to the bank and also bears any losses incurred in the loan.

Advantages of Total Return Swaps

Advantages of Total Return SwapsTRSs are exposed to interest rate risk. The payments made by the total return receiver are often equal to LIBOR plus a spread. An increase in LIBOR during the agreement increases the payment due to the payer, while a decrease in LIBOR decreases the payments to the payer.

A credit default swap option (CDS option), also known as a credit default swaption, is an option on a credit default swap. It gives its holder the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell protection on a specified reference entity for a specified future period for a certain spread.

CDS options can either be payer swaptions or receiver swaptions.

Banks use several ways to reduce their exposure to credit risk, both individually and on an aggregate basis. Such credit protection techniques include the following:

Credit Risk insurance is a critical risk-mitigation technique when protecting against a bad debt or slow payments that are not in line with the initial agreement. If the counterparty cannot pay due to a host of issues such as insolvency, political risk, and interest rate fluctuations, the credit insurer will pay. By the principle of subrogation, the insurer can then pursue the counterparty for payment. When insurance is sought on an individual obligor basis, this is termed a guarantee.

Netting is the practice of offsetting the value of multiple positions or payments due to be exchanged between two or more parties. Netting entails looking at the difference between the asset and liability values for each counterparty involved, after which the party that is owed is determined. For netting to work, there must be documentation that allows exposures to be offset against each other.

Netting frequently occurs when companies file for bankruptcy. The entity doing business with the defaulting company offsets any money they owe the defaulting company with money owed. The parties then decide how to settle the amount that cannot be netted through other legal mechanisms.

This refers to the settlement of gains and losses on a contract daily. It avoids the accumulation of large losses over time, which can lead to a default by one of the parties. As with netting, an agreement has to be in place allowing counterparties to periodically revalue a position and transfer any net value change between them so that the net exposure is minimized.

Termination describes a situation where parties develop trigger clauses in a contract that gives the counterparty the right to unwind the position using some predetermined methodology. Trigger events may include:

Historically, banks used to originate loans and then keep them on their balance until maturity. That was the originate-to-hold model. With time, however, banks gradually and increasingly began to distribute the loans. By so doing, the banks were able to limit the growth of their balance sheet by creating a somewhat autonomous investment vehicle to distribute the loans they originated. This is known as the originate-to-distribute business model.

From the perspective of the originator, the OTD model has several benefits:

To borrowers, the OTD model led to an expanded range of credit products and reduced as well as from borrowing costs.

The OTD model, however, has its disadvantages:

A direct result of the shift to the originate-to-distribute model is securitization, which involves repackaging loans and other assets into new securities that can then be sold in the securities markets. This eliminates a substantial amount of risk (i.e., liquidity, interest rate, and credit risk) from the originating bank’s balance sheet when compared to the traditional originate-to-hold strategy. Apart from loans, various other assets, such as residential mortgages and credit card debt obligations, are often securitized.

To reduce the risk of holding a potentially undiversified portfolio of mortgage loans, several originators (financial institutions) work together to pool residential mortgage loans. The loans pooled together have similar characteristics. The pool is then sold to a separate entity, called a special purpose vehicle (SPV), in exchange for cash. An issuer will purchase those mortgage assets in the SPV and then use the SPV to issue mortgage-backed securities to investors. MBSs are backed by mortgage loans as collateral.

The simplest MBS structure, a mortgage pass-through, involves cash (interest, principal, and prepayments) flowing from borrowers to investors with some short processing delay. Usually, the issuer of MBSs may enlist the services of a mortgage servicer whose main mandate is to manage the cash flow from borrowers to investors in exchange for a fee. MBSs may also feature mortgage guarantors who charge a fee and, in return, guarantee investors the payment of interest and principal against borrower default.

Practice Question

NovaCorp is concerned about the credit risk from its bond holdings in Regent Industries. The risk management team considers using Credit Default Swaps (CDS) to hedge against potential default, providing protection without requiring NovaCorp to sell its bond holdings.

Which statement correctly captures the primary advantage of using a Credit Default Swap (CDS) in NovaCorp’s situation?

A. CDS allows NovaCorp to sell its bond holdings of Regent Industries at a higher price.

B. CDS provides NovaCorp with insurance against default or a credit event of Regent Industries without needing to sell its bond holdings.

C. CDS commits NovaCorp to purchase more bonds of Regent Industries in the event of a credit downturn.

D. CDS enables NovaCorp to directly influence the financial decisions of Regent Industries.

The correct answer is B.

The primary advantage of using a Credit Default Swap (CDS) in NovaCorp’s situation, as correctly captured by option B, is that it provides NovaCorp with insurance against default or a credit event of Regent Industries without needing to sell its bond holdings. A CDS is a financial derivative that allows the holder to swap the credit risk of the underlying bond or loan with another party. In this case, NovaCorp can enter into a CDS contract to hedge against the credit risk associated with its bond holdings in Regent Industries. This means that if Regent Industries defaults or experiences a credit event, the CDS seller will compensate NovaCorp, thereby protecting it from potential losses. Importantly, this hedging mechanism does not necessitate the sale of the actual bond holdings. This allows NovaCorp to maintain its investment position in Regent Industries while simultaneously protecting itself from credit risk.

Option A is incorrect. A common misconception about CDS is that it allows the holder to sell its bond holdings at a higher price. However, this is not the case. The primary purpose of a CDS is to offer protection against credit risk, not to influence bond prices directly. While a CDS can indirectly affect bond prices by altering the perceived credit risk of the bond issuer, it does not directly enable the holder to sell its bond holdings at a higher price. Therefore, option A does not correctly capture the primary advantage of using a CDS in NovaCorp’s situation.

Option C is incorrect. Another misconception about CDS is that it commits the holder to purchase more bonds in the event of a credit downturn. This is not true. A CDS is a tool to hedge against the default risk of existing bond holdings, not a commitment to purchase more bonds. In fact, the holder of a CDS is not required to hold the underlying bond or loan at all. Therefore, option C does not correctly capture the primary advantage of using a CDS in NovaCorp’s situation.

Option D is incorrect. A CDS does not provide the holder with any influence over the financial decisions of the bond issuer. It is purely a risk management instrument that allows the holder to swap the credit risk of the underlying bond or loan with another party. Therefore, option D does not correctly capture the primary advantage of using a CDS in NovaCorp’s situation.

Things to Remember

- CDS contracts are bilateral agreements, meaning they’re between two specific parties. This is in contrast to standardized exchange-traded contracts.

- When a credit event occurs (as defined by the CDS contract), the protection seller either takes delivery of the defaulted bond for the agreed-upon price or pays the protection buyer the difference between the bond’s par value and recovery value.

- CDS contracts can be traded in the secondary market, which means their prices can fluctuate based on market perceptions of credit risk.

- Counterparty risk is a concern in CDS contracts, as either party could default on their obligations. This risk can sometimes be mitigated through collateral arrangements.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.