Verification

Verification involves an independent third party reviewing a firm’s GIPS® procedures and confirming... Read More

Distressed debt is a financial term that refers to the fixed obligations of issuers who are insolvent, at risk of insolvency, or have a higher probability of defaulting on their interest or principal payments on time.

Insolvency is a state where an entity cannot meet its debt obligations due to a lack of financial resources. The risk of insolvency is a situation where there is a high likelihood of an entity becoming insolvent. A higher probability of defaulting on interest or principal payments on time implies that the issuer is experiencing financial distress and may not be able to fulfill its debt obligations as per the agreed terms. For example, in the 2008 financial crisis, many banks were at risk of insolvency due to their exposure to subprime mortgages.

While distressed debt can involve both sovereign and corporate borrowers, the focus here is on corporate distressed issuers. Corporate distressed issuers are companies that are experiencing financial distress and are at risk of or are already unable to meet their debt obligations. A real-world example of this could be the automotive company General Motors, which declared bankruptcy in 2009 due to its inability to meet its debt obligations.

The distressed debt presents a unique avenue for investors, marked by both its high-risk and high-reward nature. This type of debt belongs to issuers whose financial instruments, be they bonds or stocks, are trading at significant discounts due to concerns over their financial health. The concept is pivotal for those in finance, offering a deep dive into the intricacies of struggling issuers.

Distressed debt is notably marked by a yield spread exceeding 1,000 basis points above a comparable risk-free rate or a loan price dipping below 90% of par. For example, bonds yielding 12% against a 2% risk-free rate highlight the distressed nature of the issuer. Similarly, equity prices teetering at the brink of minimum listing requirements also signal distress, indicating potential restructuring or bankruptcy on the horizon.

A spectrum of situations can herald financial distress, from breaches in loan agreement terms—known as technical defaults—to outright failure to meet financial obligations. Such conditions underscore the precarious position of distressed companies, which span various industries and sizes, emphasizing the necessity for thorough financial analysis.

While distressed debt investing carries inherent risks, it can yield significant returns should the issuer navigate through its troubles successfully. The discounted purchase price of such debt offers an attractive upside if the company fulfills its obligations. Conversely, bankruptcy or continued financial turmoil could result in substantial losses, making the assessment of the issuer’s financial health and reasons for distress critical before investment.

Grasping the underlying causes of a company’s financial distress is crucial for investors aiming to discern between temporary setbacks and deep-rooted structural issues. This comprehension aids in crafting informed investment strategies and managing the associated risks, ultimately guiding decisions in the volatile area of distressed debt investing.

High Leverage: Utilizing borrowed funds for operations and growth, high leverage is not inherently problematic but can lead to financial distress if combined with poor operating performance, especially in cyclical industries. The impact’s duration and severity are vital in evaluating debt restructuring options and investment opportunities.

Debt Adjustments for Liquidity Issues: To alleviate liquidity constraints, companies might renegotiate loan terms. Minor adjustments can be sufficient for temporary issues, reflecting changes in a company’s capital structure aimed at improving financial health.

Addressing Solvency through Significant Changes: For more severe solvency issues, substantial capital structure modifications are necessary. An example includes a large retailer facing challenges due to decreased cash reserves, increased inventories, and delayed receivables, necessitating significant debt restructuring or operational adjustments.

Lender’s Perspective on Short-term Solvency Issues: Lenders may opt to amend the terms of debt obligations to support companies with temporarily impaired cash flows but otherwise solid operational metrics, such as sales and margins. This could involve loan term extensions or interest rate reductions to bridge net cash flow shortfalls.

Asset Sales to Reduce Leverage: In response to cyclical downturns, issuers might sell assets to decrease leverage. This strategy was notably employed by banks during the 2008 financial crisis to strengthen balance sheets and lower leverage ratios by offloading non-core assets.

Financial distress can be instigated by significant adverse changes in the value of crucial balance sheet items. This is often precipitated by unexpected non-debt liabilities that arise from circumstances such as litigation, product recalls, or other forms of product- or customer-related liability that surpass a company’s liability insurance coverage.

Asset impairment is another key factor that can lead to financial distress. This involves a negative shift in the market value of an asset, causing the value to drop below the recorded value on the firm’s balance sheet. This can encompass changes in current assets, such as uncollectible accounts receivable, and fluctuations in the value of long-term tangible and intangible assets.

Poor Operating Performance is a critical element that can trigger financial distress within a company. Poor operating performance can be attributed to a variety of factors such as a general downturn in the industry, ineffective management practices, or a business model that fails to compete effectively. In certain scenarios, a company might find itself on the brink of insolvency due to a combination of high debt levels and poor operating performance. This situation may call for more aggressive measures such as downsizing or restructuring the business.

In 2009, GM filed for bankruptcy due to high debt levels and poor operating performance. The company had to undergo significant restructuring, including downsizing and selling off brands, to regain its financial footing.

Occasionally, a company may decide to adopt a new business model or strategy following a restructuring. However, this new model or strategy may not be sufficient to support the company’s balance sheet debt load. As a result, a new capital structure may be necessary. This new structure may hinge on the achievement of certain financial milestones, which may prove to be unattainable.

Crises of confidence or management often lead to financial distress or bankruptcy. These situations usually emerge from the revelation of fraudulent activities, aggressive accounting, or financial irregularities. The Enron scandal serves as a notable example, where executive fraud led to bankruptcy and liquidation amidst investor lawsuits.

Diagnosing the Crisis: The first step in addressing such a crisis involves a thorough analysis of the causes and severity of the declining creditworthiness. This critical assessment aids in crafting measures to stabilize and enhance company performance, as demonstrated in the General Motors bankruptcy case study.

Repercussions of Financial Irregularities: The uncovering of financial irregularities can result in drastic outcomes for a company, such as stock delisting, bankruptcy, and legal actions from investors. Despite these challenges, proper management and strategic planning can enable recovery from such crises.

Recovery and Strategic Changes: The recovery process from a management or confidence crisis entails identifying the root causes of financial distress, implementing strategies to stabilize and improve the company’s standing, and exploring investment opportunities for resurgence. General Motors’ recovery post-2009 bankruptcy, aided by strategic changes and a government bailout, exemplifies a successful turnaround from financial distress.

Understanding the nuances of credit risk is essential in financial management, highlighting the importance of addressing potential defaults and the severity of losses. Various financing strategies and alternatives exist for mitigating financial distress, tailored to the specific circumstances of the issuer, such as the nature of the financial gap and the feasibility of avoiding bankruptcy.

For issues related to short-term liquidity shortages, negotiations with liquidity providers can lead to adjustments in credit agreements, such as increased credit sizes, extended tenors, and modified covenants.

Examples include companies agreeing to higher costs or more restrictive terms in exchange for covenant adjustments.

Negotiating new financing sources or reducing financial leverage is crucial for long-term solvency, often involving asset sales to strategic buyers to avoid liquidation prices.

Assets not previously encumbered may be offered as collateral to secure new loans.

Distressed firms may raise additional debt or equity against unencumbered assets or through shareholder contributions, though unsecured financing is typically unavailable.

Equity capital raises are more debtor-friendly, often coming from existing shareholders due to time and cost efficiency.

Distressed debt exchanges offer a way to ease the debt burden by exchanging existing bonds for new securities with lower values or longer maturities, avoiding the higher costs of bankruptcy.

Debt-for-equity swaps can extinguish debt in exchange for equity, affecting the type of equity and associated rights.

Efforts to address defaults outside of bankruptcy aim to save on costs and time, with success depending on the firm’s liquidity, financial needs, and the complexity of its assets and structure. Limited liquidity and complex capital structures make immediate mitigation and restructuring challenging, emphasizing the importance of timely and strategic action.

Understanding the intricacies of complex capital structures and bankruptcy is crucial for financial analysts and investors. These structures, which often involve secured debt, covenant protections, layers of subordination, and intercreditor agreements, can limit the flexibility of borrowers and lenders to negotiate a satisfactory plan. For instance, a company like General Motors, which faced significant regulatory or external constraints such as labor contracts and pension commitments, had to seek bankruptcy protection during the 2008 financial crisis.

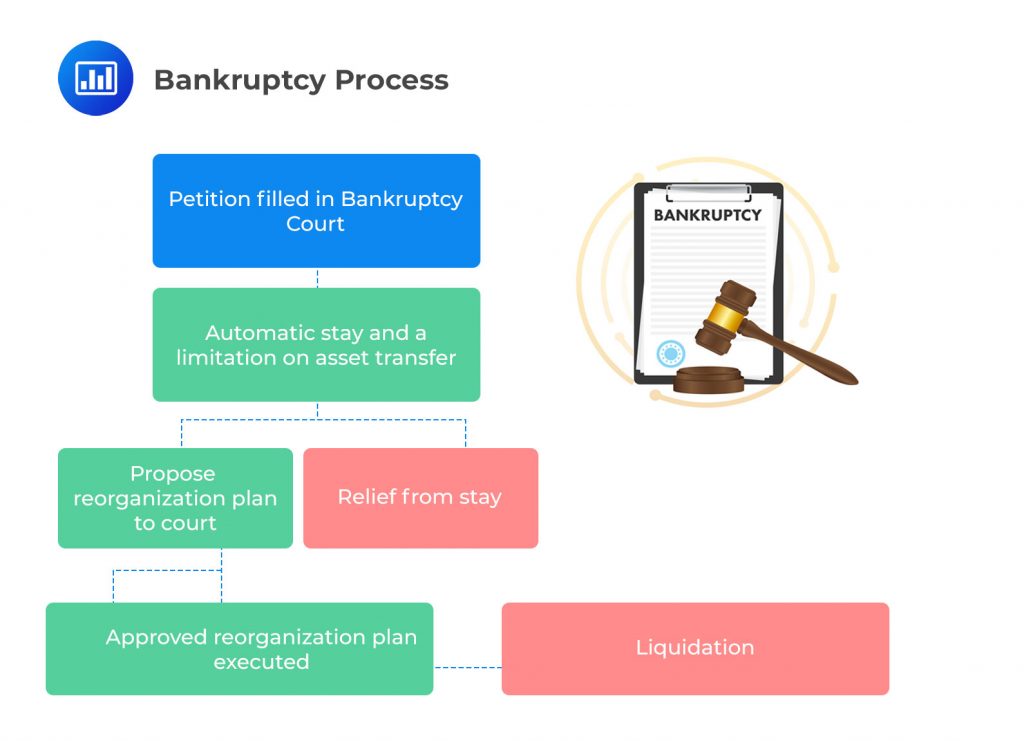

Initiation: The process starts with the filing of a bankruptcy petition in court. This can be a voluntary action by the debtor or an involuntary action taken by creditors. The petition triggers an automatic stay that immediately stops most collection actions against the debtor, providing temporary relief.

Appointment of Trustee: In Chapter 7 cases, the court appoints a trustee to oversee the liquidation of assets. In Chapter 11 cases, the debtor often remains in control as a debtor in possession (DIP), but under the court’s supervision, to manage business operations and the restructuring process.

Creditors’ Meeting: After the bankruptcy filing, a meeting of creditors is held, where they can question the debtor about their financial situation and the plans for reorganization or liquidation.

Submission of Financial Documents: The debtor is required to submit detailed schedules of assets and liabilities, income and expenses, and a list of all contracts and unexpired leases. This transparency helps the court and creditors assess the debtor’s situation.

Plan Proposal (Chapter 11): In Chapter 11 bankruptcies, the debtor proposes a reorganization plan detailing how it will operate and pay creditors over time. This plan must be voted on by creditors and confirmed by the court.

Liquidation (Chapter 7): If reorganization is not feasible, Chapter 7 involves liquidating the debtor’s assets to pay off creditors. The court-appointed trustee sells the debtor’s non-exempt assets and distributes the proceeds to creditors according to the priorities established by law.

Plan Confirmation and Implementation (Chapter 11): Once a reorganization plan is approved by creditors and confirmed by the court, the debtor begins to implement the plan, potentially including selling assets, renegotiating terms, or other strategies to pay back creditors.

Discharge: After the bankruptcy process is complete, the debtor receives a discharge, which releases them from personal liability for certain types of debts. This does not apply to all types of debts, and specific obligations may remain, depending on the bankruptcy chapter.

Fraudulent Conveyance: The bankruptcy process includes mechanisms to address fraudulent conveyance—transactions made to evade creditors. These can be reversed if they occurred within a certain period before the bankruptcy filing.

DIP Financing: Firms seeking to continue operations propose a reorganization plan under a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing. The company becomes a debtor in possession (DIP), remaining in control of the business under court supervision. For example, American Airlines filed for Chapter 11 in 2011, but continued to operate while restructuring its debt. A debtor may submit a proposal to the court to obtain DIP financing, a form of temporary debt financing senior to all other claims used to cover ongoing bankruptcy costs and provide working capital.

Governmental and International Cases: Special chapters of the bankruptcy code, like Chapters 9 for municipal bankruptcies and 15 for international cases, address unique situations, each with its specific process and rules. In some cases, large companies considered to operate in the national economic interest may benefit from a form of direct or indirect government support such as loan guarantees or subsidies when facing financial distress. For instance, during the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. government provided financial support to companies like General Motors and AIG.

Out-of-Court and Prepackaged Bankruptcies: Out-of-court restructurings may be negotiated quickly but typically require agreement of all creditors to proceed. A prepackaged bankruptcy involves a detailed business plan and exit strategy formulated by the debtor and agreed on with one or more major creditors in advance of bankruptcy filing. This typically accelerates the process, reduces the likelihood of liquidation, and increases an issuer’s ability to attract equity capital once it emerges from bankruptcy. For example, Six Flags used a prepackaged bankruptcy to restructure its debt in 2009.

Free Fall Bankruptcy: A scenario with no pre-negotiated plan, leading to a potentially more uncertain and costly process. If the onset of financial distress is sudden or unexpected, an issuer is more likely to enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy in a free fall bankruptcy, or one with no plan or pre-agreement with creditors. This is usually more expensive and time consuming, with a less certain outcome. For instance, Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy in 2008 is considered a free fall bankruptcy.

Practice Questions

Question 1: In the field of finance, distressed debt refers to certain fixed obligations. Which of the following best describes the issuers of distressed debt?

- Issuers who are solvent and have a low probability of defaulting on their interest or principal payments on time.

- Issuers who are insolvent, at risk of insolvency, or have a higher probability of defaulting on their interest or principal payments on time.

- Issuers who are solvent and have a high probability of making their interest or principal payments on time.

Answer: Choice B is correct.

Distressed debt refers to the debt of companies or government entities that are in financial distress or have already filed for bankruptcy protection. The issuers of distressed debt are typically insolvent, at risk of insolvency, or have a higher probability of defaulting on their interest or principal payments on time. These issuers are often unable to meet their financial obligations and are likely to default on their debt payments. Investors in distressed debt are essentially betting that the distressed company will be able to turn around its fortunes and meet its debt obligations, or that they will be able to recover more in a bankruptcy proceeding than the price they paid for the debt. This type of investing is considered high risk and requires a deep understanding of the company’s financial situation and the potential outcomes of a bankruptcy proceeding.

Choice A is incorrect. Issuers who are solvent and have a low probability of defaulting on their interest or principal payments on time are not considered issuers of distressed debt. These issuers are typically in a strong financial position and are able to meet their debt obligations on time.

Choice C is incorrect. Issuers who are solvent and have a high probability of making their interest or principal payments on time are also not considered issuers of distressed debt. These issuers are typically in a strong financial position and are able to meet their debt obligations on time. The term “distressed debt” specifically refers to the debt of issuers who are in financial distress or have a high probability of defaulting on their debt payments.

Question 2: The concept of distressed debt applies to various types of borrowers. However, the primary focus of these notes is on a specific type of distressed issuers. Which type of distressed issuers is the primary focus of these notes?

- Sovereign distressed issuers

- Corporate distressed issuers

- Individual distressed issuers

Answer: Choice B is correct.

The primary focus of distressed debt notes is on Corporate Distressed Issuers. Distressed debt refers to the securities of a government or company that has either defaulted, is under bankruptcy protection, or is in financial distress and moving toward the aforementioned situations in the future. The term is primarily used to refer to a situation where a business cannot meet or has difficulty paying off its financial obligations to its creditors, typically due to high fixed costs, illiquid assets, or revenues sensitive to economic downturns. Corporate distressed issuers are companies that have filed for bankruptcy or are expected to do so in the near future. Investors in distressed debt often seek to profit from the potential for a rise in the debt’s price if the company’s situation improves, or from the potential payout if the company is liquidated.

Choice A is incorrect. Sovereign distressed issuers refer to governments that are unable to meet their debt obligations. While this is a type of distressed issuer, it is not the primary focus of these notes. Sovereign debt crises can be extremely complex and often involve negotiations with international financial institutions and other governments, making them less suitable for the strategies typically employed by distressed debt investors.

Choice C is incorrect. Individual distressed issuers refer to individuals who are unable to meet their debt obligations. This is not the primary focus of these notes. Individual distressed debt is typically handled through personal bankruptcy proceedings, and is not a major focus for most investors.

Glossary:

Private Markets Pathway Volume 2: Learning Module 5: Private Special Situations; LOS 5(b): Discuss the features of distressed debt, financing alternatives for issuers in financial distress, and investment strategies in distressed situations

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.