Hedge Funds

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Explain biases that... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

Sources of funding in banks can become unstable, and the global financial crisis proved this. During the crisis, the majority of the banks had a hard time acquiring short-term U.S. dollar funding. Thus, this led to central banks across the world employing extreme policy approaches, such as international swap arrangements with the U.S. Federal Reserve. The reason was to be able to supply commercial banks with U.S. dollars per their jurisdictions.

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) identified reasons for the U.S Dollar shortage during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) as follows:

The investors had an overwhelmingly high thirst for the so-called “safe haven” or foreign currency assets, notably the U.S.-denominated claims on non-bank entities. The funding difficulty during the GFC had a direct relation to banks’ global balance sheet expansions over the past decade before the crisis. Thus, the growth of banks’ balance sheets respectively heightened their thirst for foreign currency assets.

This refers to the extent to which banks invest in one currency and fund in another via F.X. swaps. Europe and Japan banking systems mainly engaged in cross-currency funding. Since 2000, the two banking systems took enormous amounts of the net on-balance-sheet positions in foreign currencies, especially in U.S. dollars. The associated currencies exposures were left hedged off-balance-sheet since the accumulation of net foreign currency position led to a situation where the banks were on a foreign currency funding risk. In other words, these banks were exposed to the risk that their funding positions could not be rolled over.

Unlike domestic banks, non-US banks had limited access to a stable base of dollar deposits. This means that they relied on short-term and potentially more volatile sources of funding, such as commercial paper and loans from other banks. A lower bound approximate of banks’ funding gap, which is the net amount of U.S. dollars channeled to non-banks, shows the vast funding needs of the major European banks. It became more complicated to secure this funding after the onset of the crisis. This is because, after the GFC, credit risk concerns led to disruptions in the interbank and F.X. swap markets as well as in money market funds. European banks reacted to these disruptions through the support of central banks.

The dollar profited from the unwinding of carry trades. A carry trade involves an investor holding a high-yielding currency asset (target asset), which is financed with a low-yielding currency liability (funding liability). When financial markets become very volatile, the target currencies with the most lucrative yields significantly depreciate, and the funding currencies appreciate. This was the case during the GFC. The dollar interest rates decline by mid-2008 had already recommended the dollar to carry traders as a funding currency alongside the yen.

When equity volatility rose, the higher currency’s yield in the previous six months implied a higher depreciation against the dollar. Target currencies were struck (hit hard) as investors sold them against the dollar or yen.

Many banks invested heavily in the U.S. dollar assets until mid-2007. They funded these positions by borrowing dollars directly from various counterparties, as well as using foreign exchange swaps.

Dollar asset declines left institutional investors outside the United States over-hedged. European banks were forced to buy dollars in the spot market as they wrote down the value of holdings of dollar securities. The aim was to retire the corresponding hedges. On the same note, European pension funds bought the dollar as they experienced losses on dollar securities hedged into the euro.

Stress accumulates on a global bank’s balance sheet in the form of assets and liabilities maturity or currency mismatches, and understanding these mismatches can only be achieved by looking into the bank’s worldwide positions consolidated across all office locations. For a bank aiming to expand globally, it needs to fund a specific portfolio of securities and loans in which some of it is based on foreign currencies.

Banks can finance these foreign currency positions through:

Banks get vulnerable to funding risks as a result of the different options of funding or in situations where they are unable to roll over funding liabilities. The degree of maturity transformation associated with a bank balance sheet is what determines the implications of the risk. The need to invest relies on the preferred holding period, market liquidity, and the underlying asset’s maturity. In case the rolling over of the contractual liabilities is not possible, the foreign currency assets meant for holding are rather sold and more likely in conditions of distressed market situations. A funding gap refers to the amount that banks must rollover before the maturity of their investments

Technically, funding risk is associated with stresses on a broad basis on the global balance sheet: the mismatches between currency, maturity, and counterparty of liabilities and assets. In quantifying these threats, there is a need to measure banking activities based on consolidation, specifically at the individual bank level (the decision-making economic unit).

Data on a clear breakdown of positions per currency, liabilities, assets, counterparty and maturity type, as well as off-balance sheet positions, are meant to assist in identifying potential mismatches. However, the available public information fails to factor in this idea. Although published bank accounts on a consolidated level are available, they lack essential information on the breakdown of maturity, counterparty, and currency required.

The structure of the individual bank’s global balance sheet entails summing up the local and cross-border balance sheet positions from its domestic offices and the host states around the globe into a consolidated whole for each banking system.

Banks that are actively operating across the world have numerous offices in various countries. Their management of maturity and currencies are based on a consolidated global entity instead of per office. This implies that significant mismatches measured on an office’s balanced sheet located in a different office may be offset/hedged off-balance sheet through an on-balance sheet position booked by other offices elsewhere. This results in a matched book for the bank as a whole.

The banks’ international balance sheet expansions since 2000 are highly associated with the U.S. dollar shortage. The stocks on banks’ foreign claims significantly grew from $10 trillion at the start of 2000 to $34 trillion by the end of 2007. By 2001, international claims were at 10% while at the end of 2007, it approached 30%. These significant changes occurred mainly during the financial innovation period. It included expansion growth in the hedge fund industry, the introduction of financial structures, and the spreading of universal banking, which combined proprietary trading, investment, and commercial banking activities.

In 1999, there was the introduction of the Euro, leading to increased activity in the European banking system, and the outcome was significant intra-euro area lending. The European bank positions dominated in U.S. dollar and other non-euro currencies is responsible for most of the overall expansion in their foreign assets between the end of 2000 and the mid of 2007.

In banking, maturity transformation plays a critical role. Necessarily, banks are required to make the transfer of funds from agents in excess (demanding short-term deposits) to agents in deficit (with long-term financing needs). The maturity mismatch needed for the facilitation of long-term investment projects, as well as serving the liquidity needs of the investor, should allow banks to earn a positive spread.

Banks might get motivated to excessively increase their maturity mismatch, thus rendering themselves vulnerable to funding risks embedded in rolling-over short-term liabilities. Excessive maturity transformation creates undesirable financial stability issues as it puts the entire banking system at risk.

A dollar shortage refers to a scenario where a country lacks a sufficient supply of U.S. dollars for effectively managing international trades. This situation comes into place when a country is required to pay more U.S. dollars for its imports as compared to the U.S. dollars received from exports.

Most countries have to hold their assets in dollars to sustain the steady growth of the economy and transact with other countries who use the U.S. dollar since it is the globe’s key traded currency.

When a dollar shortage occurs, it affects global trade since the U.S. dollar acts as a peg for other currencies’ value. During the GFC, maturity transformation was unsustainable since the leading banks’ sources of short-term funding were unstable. Short-term interbank funding got compromised by increased counterparty liquidity risk. The associated disarrangements in F.X. swap markets made it even worse, as it was expensive to acquire U.S. dollars through currency swaps. On the other hand, the European bank’s U.S. dollar funding needs were more than other entities’ funding requirements in different currencies.

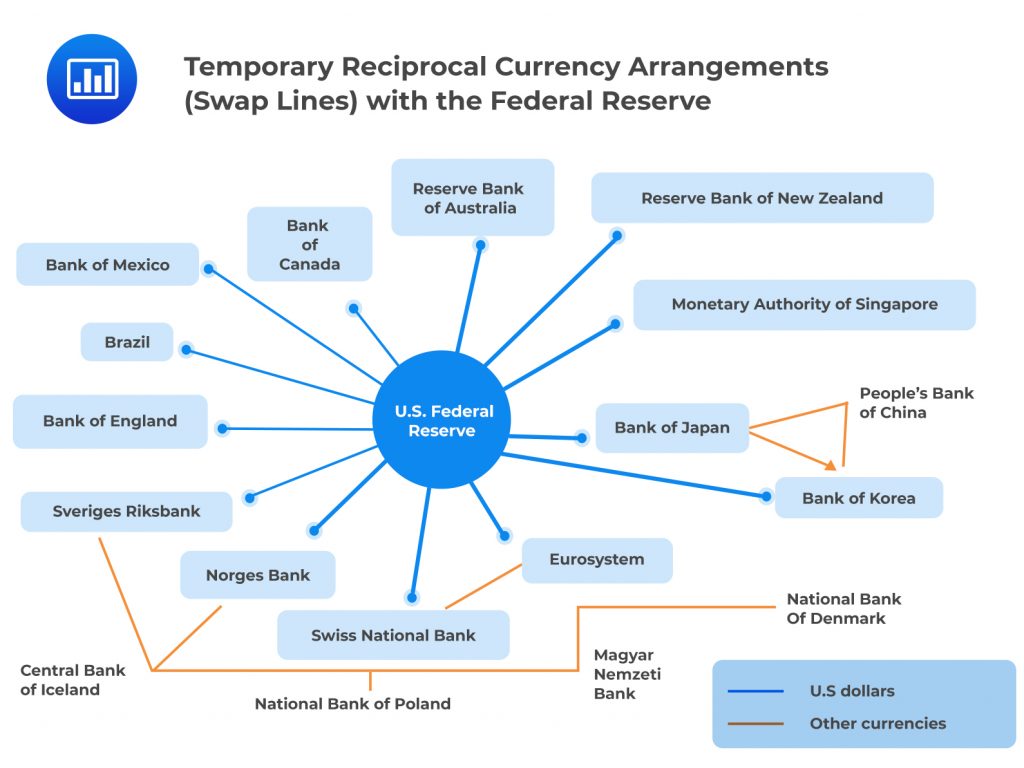

International policy response came into place due to the severe U.S. dollar shortage among banks outside the United States. The European Central Bank embraced measures to relieve funding pressures in their domestic currencies since they were unable to avail of adequate U.S. dollar liquidity. They thus opted for temporary reciprocal currency arrangements (swap lines with the Federal Reserve) to have U.S. dollars directed to banks with their corresponding jurisdictions.

Through providing the U.S. dollars on a worldwide scale, the Federal Reserve technically participated in international lending of last resort.

The Success of the International Policy Response

The Success of the International Policy ResponseThe international swap arrangements mitigated two main challenges, mainly related to international lending of last resort. These included:

Question

Northern Lights Bank (NLB), headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, has a complex international operation with several foreign branches, including a significant presence in the US and Japan. Its assets in the US include long-term corporate bonds and US treasuries. Furthermore, NLB has taken a substantial position in the Japanese market, focusing on yen-denominated securities. Their funding mechanism primarily relies on short-term interbank borrowing and Foreign Exchange (FX) swaps.

At the end of 2022, data revealed the following:

- NLB’s long-term assets in the US are valued at $500 billion, with its short-term liabilities at $350 billion.

- In Japan, NLB’s long-term yen-denominated assets are worth ¥7 trillion, and its short-term liabilities stand at ¥5 trillion.

- NLB typically uses FX swaps to hedge its currency exposure.

- Sweden’s central bank recently announced that it could provide emergency liquidity in domestic currency but not in foreign currencies.

Given the data above, which of the following statements is most likely correct?

A. Currency mismatch is the primary concern for NLB given its extensive operations in the US and Japan.

B. The mismatch is insignificant as long as NLB can rely on FX swaps to hedge its currency exposure.

C. NLB’s maturity mismatch in foreign operations exposes it to significant funding risks, especially if it cannot roll over its short-term liabilities.

D. With emergency liquidity available from the Swedish central bank, NLB’s maturity mismatch is of minimal concern.

Solution

The correct answer is C.

Given the information, NLB has a larger amount of long-term assets compared to its short-term liabilities in both the US and Japan. This exposes the bank to the risk of not being able to roll over its short-term liabilities, which could force it to sell its long-term assets in a pinch, potentially incurring significant losses. While NLB can rely on FX swaps to manage currency risk, it does not mitigate the maturity mismatch and the related funding risks. Additionally, the fact that the Swedish central bank cannot provide emergency liquidity in foreign currencies exacerbates this risk.

A is incorrect because, while currency mismatch is a concern for international operations, the vignette emphasizes that NLB typically uses FX swaps to hedge its currency exposure. Therefore, the primary concern revolves around the maturity mismatch of its assets and liabilities.

B is incorrect because relying on FX swaps can help hedge against currency risk, but it does not address the maturity mismatch between long-term assets and short-term liabilities. This maturity mismatch is a primary source of funding risk for NLB.

D is incorrect since the Swedish central bank’s ability to provide emergency liquidity is limited to the domestic currency. This does not aid NLB when they face funding risks in foreign jurisdictions, such as the US and Japan, where their assets and liabilities are denominated in different currencies.

Things to Remember

- Maturity Mismatch refers to discrepancies between the maturities of assets and liabilities, exposing consolidated entities to liquidity risks.

- Currency Mismatch arises when assets and liabilities are denominated in different currencies, leading to potential financial losses from exchange rate fluctuations.

- Interrelation means that the simultaneous presence of maturity and currency mismatches can amplify the overall risk and constrain operational flexibility.

- Risk Management necessitates strategies like diversifying funding sources, hedging foreign exchange exposures, and maintaining liquidity cushions to handle these mismatches.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.