Buyout Equity Investments.

Buyout equity investments are a unique type of investment that differs from venture... Read More

Active fixed-income managers are tasked with the selection of spread-based bond portfolio investments. Their goal is to maximize excess spread across various fixed-income issuer types, industries, and instruments within their investment mandate. The decision-making process may involve an individual security selection process or a bottom-up approach, a macro- or market-based, top-down approach, or a combination of both.

Fundamental credit analysis evaluates an issuer’s capacity to fulfill interest and principal payments through bond maturity, focusing on factors like profitability and leverage. These are compared against industry norms and regional conditions to assess cash flow stability. For sovereign borrowers, the focus shifts to economic activity and the government’s ability to generate revenue through taxation. In contrast, analysis of special purpose entities issuing securitized bonds centers on the credit quality of borrowers and the collateral value, including internal credit enhancements.

While credit ratings provided by major agencies are commonly used to categorize bonds into investment grade or high yield, active managers typically conduct their own assessments to tailor investment strategies and ensure precise benchmarking. This independent credit evaluation helps managers not only adhere to investment mandates but also navigate through the complexities of various bond markets.

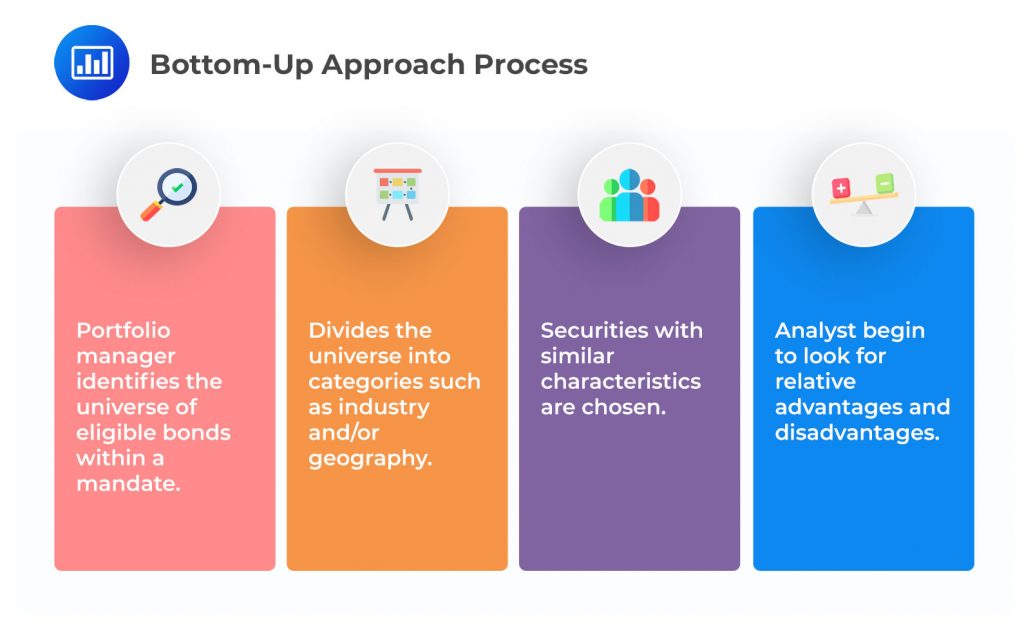

In the bottom-up approach of bond portfolio management, defining the credit universe is a pivotal step. This involves the portfolio manager identifying eligible bonds within a specific mandate and categorizing them into groups for consistent relative value analysis across comparable borrowers.

For instance, consider a portfolio manager overseeing a corporate bond portfolio. They might segregate the eligible bonds into industry sectors like technology, healthcare, and finance. These sectors can be further divided into subsectors or companies based in different regions. For example, the technology sector could be subdivided into software companies, hardware manufacturers, and internet service providers.

The categorization can be based on standard industry classification methodologies or a tailored approach. Once the sectors and subsectors are defined, the manager can employ relative value analysis to identify the most attractively valued bonds.

Bottom-Up Credit Analysis is a technique employed by investors to assess the inherent credit risk of individual issuers. This is achieved by juxtaposing company-specific financial data with spread-related compensation for potential default, credit migration, and liquidity risks. The ultimate goal is to evaluate creditworthiness across different firms.

Financial ratios are essential in Bottom-Up Credit Analysis, providing a consistent framework for comparing firms across industries and over time. Despite their utility, reliance solely on these ratios can lead to inaccuracies due to the comparability issues among different industries and the historical nature of financial data. To address this, alternative measures combine key financial ratios with market-based metrics to offer a more forward-looking assessment of creditworthiness.

Statistical credit analysis models further refine the assessment of an issuer’s credit risk. These models are broadly categorized into reduced form and structural credit models. Reduced form models focus on calculating default intensity or the Probability of Default (POD) over a certain period, incorporating observable company-specific variables like financial ratios, recovery assumptions, and macroeconomic factors such as economic growth and market volatility.

Structural credit models employ market-based variables to estimate the market value of an issuer’s assets and the volatility of asset value. The likelihood of default is defined as the probability of the asset value falling below that of liabilities.

Understanding credit risk models is crucial for financial analysts and investors. These models, such as the Z-score and structural credit models, provide insights into the financial health of a company and its likelihood of defaulting on its obligations.

Developed by Altman in 1968, the Z-score is a composite score that combines various factors such as liquidity, profitability, asset efficiency, and market versus book value of equity. These factors are weighted by coefficients. For instance, a company like Apple Inc. would have a high Z-score due to its strong liquidity and profitability. The Z-score is used to classify manufacturing firms into those expected to remain solvent and those anticipated to go bankrupt.

Structural credit models like Moody’s Analytics Expected Default Frequency (EDF) and Bloomberg’s Default Risk (DRSK) models provide daily Probability of Default (POD) estimates for a broad range of issuers over a selected period. For example, the EDF model might estimate a higher POD for a startup company in a volatile industry compared to a well-established company in a stable industry. The DRSK model provides estimates for specific companies, such as AbbVie Inc.

Bottom-Up Relative Value Analysis is a strategic approach employed by investors to determine the most profitable bonds to invest in. This decision is primarily based on the yield spread and credit risk associated with each bond. For instance, if two issuers present similar credit risks, investors are likely to opt for the bonds with a higher yield spread, offering a greater potential for excess returns. However, if the credit-related risks vary, the investor must assess whether the additional spread sufficiently compensates for the increased risk exposure.

While yield spreads and credit risk are significant factors, other characteristics such as maturity, embedded call or put provisions, and liquidity also play a crucial role in bond selection. For example, bonds issued in larger tranches by frequent issuers often have narrower bid-offer spreads and higher daily transaction volumes, reducing the cost for investors to buy or sell. This feature is particularly beneficial for investors anticipating short-term spread narrowing or those with a short investment time horizon.

Over time, relative liquidity tends to decrease, especially if the issuer re-enters the bond market offering a price concession for new debt. Long-term investors with the flexibility to hold a bond to maturity may increase excess return through a higher liquidity premium.

Other factors to consider include split ratings or negative ratings outlooks, potential merger and acquisition activity, and other company events not adequately reflected in the analysis.

Investors often face the challenge of choosing among frequent issuers with multiple bond issues. In such scenarios, credit spread curves can be a valuable tool for gauging relative value. These curves are developed for each issuer, reflecting the various maturities of their bonds, and are instrumental in conducting relative value analysis.

A credit spread curve is essentially a graph of credit spreads for similar bonds from the same issuer, plotted against the maturity of those bonds. For instance, if Company A and Company B both issue bonds with similar features and liquidity, a manager might infer from the spread curve that the market perceives Company A’s credit risk to be slightly higher than Company B’s.

However, if the manager believes that Company A, despite the perceived higher risk, is the stronger credit, several strategies can be adopted depending on portfolio objectives and constraints. For instance, if the goal is to outperform a benchmark using long-only positions, the manager might overweight Company A’s bonds and underweight Company B’s bonds relative to the benchmark. If the objective is absolute returns, underweighting or avoiding Company B’s bonds may not be the best strategy. In such a case, if allowed, the manager could consider a long-short CDS strategy.

After identifying specific issuers and bond maturities to actively over- or underweight versus a benchmark, it’s crucial to quantify and track these active investments. For example, if an investor decides to overweight specific issuers in the healthcare industry versus the sector and spread duration contributions of the benchmark index, the difference in portfolio weights between the active and index positions establishes a basis for measuring excess return.

Practice Questions

Question 1: Active fixed-income managers have a variety of strategies at their disposal when selecting spread-based bond portfolio investments. These strategies can be broadly categorized into individual security selection or a bottom-up approach, a macro- or market-based, top-down approach, or a combination of both. When considering the factors that influence the selection of these strategies, which of the following is not typically a consideration for active fixed-income managers when evaluating potential bond investments?

- The credit rating assigned by major credit rating agencies.

- The economic activity within a government’s jurisdiction and its ability to generate sufficient revenue to meet its obligations.

- The profitability and leverage of the issuer, as well as the sources and variability of cash flows available to service debt.

Answer: Choice B is correct.

The economic activity within a government’s jurisdiction and its ability to generate sufficient revenue to meet its obligations is not typically a consideration for active fixed-income managers when evaluating potential bond investments. This is because the economic activity within a government’s jurisdiction is more relevant to equity investors who are interested in the growth prospects of companies within that jurisdiction. Fixed-income investors, on the other hand, are more concerned with the issuer’s ability to meet its debt obligations, which is more closely related to the issuer’s financial health and creditworthiness. Therefore, while the economic activity within a government’s jurisdiction may indirectly affect the issuer’s ability to service its debt, it is not a primary consideration for fixed-income investors.

Choice A is incorrect. The credit rating assigned by major credit rating agencies is a key consideration for active fixed-income managers when evaluating potential bond investments. Credit ratings provide an independent assessment of the creditworthiness of an issuer, which is a critical factor in determining the risk and potential return of a bond investment.

Choice C is incorrect. The profitability and leverage of the issuer, as well as the sources and variability of cash flows available to service debt, are also important considerations for active fixed-income managers. These factors provide insight into the issuer’s financial health and its ability to meet its debt obligations, which are key determinants of the risk and potential return of a bond investment.

Question 2: Statistical credit analysis models are used to measure individual issuer creditworthiness. These models can be categorized as either reduced form credit models or structural credit models. What is the main difference between a reduced form credit model and a structural credit model?

- Reduced form models solve for default intensity, while structural models estimate the market value of an issuer’s assets

- Reduced form models use market-based variables, while structural models use company-specific variables

- Reduced form models estimate the market value of an issuer’s assets, while structural models solve for default intensity

Answer: Choice A is correct.

Reduced form credit models and structural credit models are two types of statistical credit analysis models used to measure the creditworthiness of individual issuers. The main difference between these two types of models lies in what they solve for. Reduced form credit models solve for default intensity, while structural models estimate the market value of an issuer’s assets. In a reduced form model, the default intensity is a random process that is calibrated to market data. The model does not make any assumptions about the issuer’s financial structure or the economic factors leading to default. On the other hand, structural models, also known as Merton models, are based on the firm’s capital structure. They estimate the market value of a firm’s assets and compare it with the firm’s liabilities. If the value of the assets falls below a certain threshold, typically the value of the firm’s liabilities, the firm is considered to be in default.

Choice B is incorrect. Both reduced form models and structural models can use market-based variables and company-specific variables. The main difference between the two models is not the type of variables they use, but what they solve for.

Choice C is incorrect. This choice reverses the roles of the two types of models. It is the structural models that estimate the market value of an issuer’s assets, while reduced form models solve for default intensity.

Portfolio Management Pathway Volume 2: Learning Module 6: Fixed-Income Active Management: Credit Strategies.

LOS 6(a): Discuss bottom-up approaches to credit strategies.

LOS 6(b): Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of credit spread measures for spread-based fixed-income portfolios, and explain why option-adjusted spread is considered the most appropriate measure

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.