Use of Ratio Analysis in Earnings Fore ...

Analysts often need to forecast future financial performance, such as EPS forecasts and... Read More

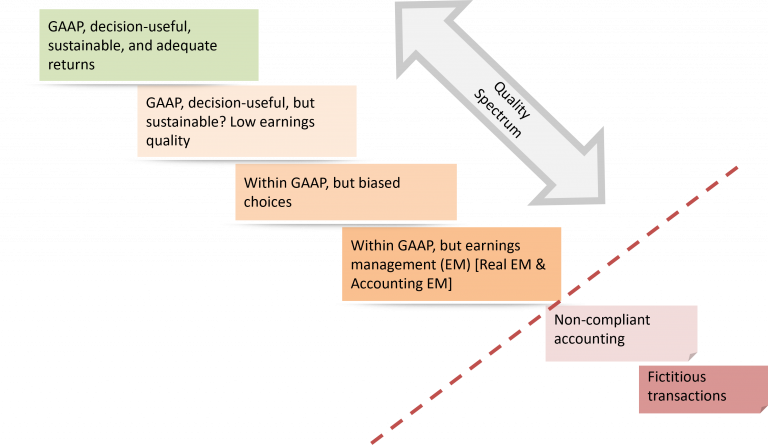

The spectrum of financial reporting quality serves as a basis for evaluating the quality of different reports. This spectrum ranges from high-quality financial reports with sustainable earnings to reports that are unreliable and lack useful information due to poor financial reporting quality, as shown below:

GAAP, Decision-useful, Sustainable, and Adequate Returns

At the top of the quality spectrum, marked as “GAAP, decision-useful, sustainable, and adequate returns” in the above diagram, are high-quality reports that deliver valuable information about high-quality earnings, with the following aspects:

The second level down in the spectrum, marked as “GAAP, decision-useful, but sustainable?” represents situations where high-quality reporting provides useful information, but the results or earnings reflected in that information are not sustainable, indicating lower earnings quality.

Specifically, the earnings may not be sustainable because the company is unlikely to generate the same return on investment in the future. This could be due to various reasons, such as market changes, competitive pressures, or internal challenges. Alternatively, the earnings might be replicable, but they do not generate a sufficient return on investment to support the company’s long-term viability. In both scenarios, the quality of earnings is low.

Note that high-quality reporting can still exist even if the economic reality it represents is not of high quality.In other words, despite the less favorable economic situation, financial reporting can still be of high quality if it accurately and clearly conveys this reality, offering decision-useful information to users.

The next level down in the spectrum marked as “Within GAAP, but biased choices” refers to situations where financial reports comply with GAAP but include biased choices that do not faithfully represent the economic substance of the reported information. Biased choices can affect not only the reported amounts but also how information is presented

Bias in financial reporting, like any other deficiencies, hampers an investor’s ability to accurately assess a company’s past performance, forecast future performance, and appropriately value the company. Some of the biased choices include:

The next level, “Within GAAP, but ‘earnings management” in the spectrum, involves earnings management, which refers to intentional choices that result in biased financial reports. This involves deliberate actions to manipulate reported earnings and how they are perceived by stakeholders.

The primary difference between earnings management and biased choices is the intent behind the actions. While biased choices may lead to unintentional misrepresentation, earnings management is characterized by intentional efforts to manipulate financial outcomes.

Earning management can represent itself in through real or accounting choices. In the real actions companies may take specific actions to influence earnings, such as postponing research and development (R&D) expenses to the next reporting period, thereby increasing current period earnings.

On the other hand, in accounting decisions, companies can also manage earnings through accounting decisions. This includes adjusting estimates for product returns, bad debt expense, or asset impairment to create higher reported earnings.

Generally, whether through real actions or accounting decisions, the goal of earning management is to influence the reported financial performance in a way that may not accurately reflect the company’s true economic condition.

Due to the difficulty in determining intent, earnings management is included under the biased choices.

The “Non-Compiant Accounting” level of the spectrum represents deviations from GAAP, which generally indicate low-quality financial reporting. In such cases, assessing earnings quality becomes challenging or even impossible due to the lack of comparability with previous periods or other entities.

For example, improper accounting displayed itself in 2007, when New Century Financial issued large amounts of subprime mortgages but reserved only minimal amounts for potential loan repurchase losses, consequently leading to its filing for bankruptcy.

At the bottom of the quality spectrum, fabricated reports depict fictitious events to mislead investors or conceal fraudulent asset misappropriation. For example, in 2004, Parmalat, an Italian milk processing conglomerate, reported fictitious bank balances to the tune of $4.5 billion, which lead to arrests of chief executive offices and other executives, among other consequences.

Although companies can make choices within GAAP to present a desired economic picture, non-GAAP reporting adds an additional layer of management discretion. Non-GAAP reporting includes financial metrics that do not comply with generally accepted accounting principles like US GAAP or IFRS. These metrics can be both financial and operational:

Non-GAAP financial reporting has become increasingly prevalent, posing challenges for analysts. One significant challenge is that non-GAAP reporting reduces comparability across financial statements. Companies’ adjustments to create non-GAAP earnings are generally ad hoc and vary widely. Analysts must carefully evaluate which specific adjustments should be considered in their analyses and forecasts.

Another challenge is the variation in terminology. Non-GAAP earnings may be referred to as underlying earnings, adjusted earnings, recurring earnings, core earnings, or similar terms. Companies might emphasize non-GAAP measures to divert attention from less favorable GAAP results, which is an example of aggressive presentation.

Since 2003, if a company uses a non-GAAP financial measure in an SEC filing, it must display the most directly comparable GAAP measure with equal prominence and provide a reconciliation between the non-GAAP and GAAP measures. This ensures that non-GAAP financial measures are not given undue prominence.

Similarly, the IFRS Practice Statement “Management Commentary,” issued in December 2010, requires disclosures when non-IFRS measures are included in financial reports. Companies must disclose when financial statement information has been adjusted for inclusion in management commentary. They must define and explain non-IFRS measures, including their relevance, and reconcile these measures to those presented in the financial statements.

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published guidelines in October 2015 on Alternative Performance Measures (APMs). These guidelines cover the definition of APMs, reconciliation to GAAP, explanation of metrics’ relevance, and consistency over time.

Poor reporting quality often accompanies poor earnings quality. For example, aggressive accounting choices might be used to mask poor performance. However, it is also possible for poor reporting quality to coexist with high-quality earnings. A company performing well might still produce low-quality reports due to inadequate internal systems or deliberate, conservative accounting choices to manage external perceptions or future financial trajectories.

For example, a company might adopt conservative accounting to avoid political scrutiny or defer profit recognition to future periods, creating hidden reserves. These choices can make future results look more favorable by accelerating losses in earlier periods.

While unbiased financial reporting is ideal, some investors may prefer conservative reporting over aggressive reporting, as positive surprises are generally easier to handle than negative ones. Nevertheless, any form of biased reporting, whether conservative or aggressive, impairs the ability of users to accurately assess a company’s performance.

In summary, the quality spectrum suggests that poor underlying economic conditions are often the main driver of poor reporting quality. However, a certain level of reporting quality is necessary to evaluate earnings quality effectively. As one moves down the quality spectrum, the distinction between reporting quality and earnings quality becomes less clear.

Question 1

Which of the following statements is the most accurate?

- Conservative accounting choices may lead to upward biases in current-period financial reports.

- Aggressive accounting choices may lead to downward biases in current-period financial reports.

- Conservative accounting choices may lead to downward biases in current-period financial reports.

Solution

The correct answer is C.

Conservative accounting choices may lead to downward biases in current-period financial reports. This results from conservative accounting choices decreasing a company’s reported performance and financial position in the current period.

A is incorrect because conservative accounting choices lead to downward biases and not upward biases in current-period financial reports.

B is incorrect because aggressive accounting choices lead to upward biases and not downward biases in current-period financial reports.

Question 2

Concerning conservatism and aggressiveness, what are the preferences of managers, investors, and regulators?

- Managers prefer aggressiveness, investors prefer conservatism, and regulators prefer neutrality.

- Managers prefer aggressiveness, investors prefer conservatism, and regulators prefer conservatism.

- Managers prefer conservatism, investors prefer aggressiveness, and regulators prefer aggressiveness.

Solution

The correct answer is A.

Managers prefer aggressiveness since compensation is mainly tied to the company’s financial performance. Investors prefer conservatism since they prefer good surprises over bad surprises. Regulators prefer neutrality because they want the financial results to reflect the company’s actual position.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.