The Foreign Exchange Market

[vsw id=”Kh3Lq2F_D3Q” source=”youtube” width=”611″ height=”344″ autoplay=”no”] Functions of the Foreign Exchange Market The... Read More

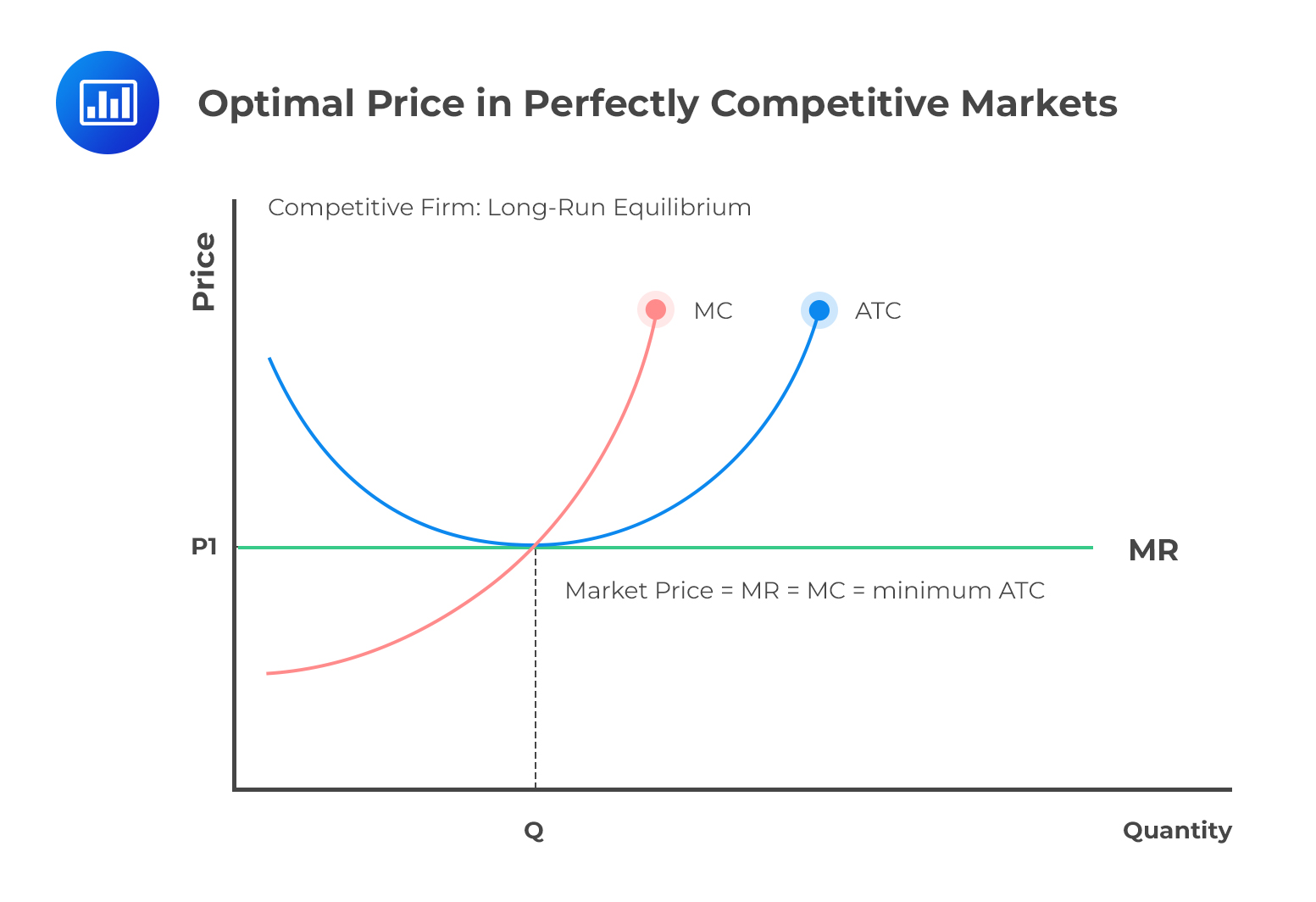

A firm is said to be at equilibrium if the marginal cost (MC) is equal to marginal revenue (MR), and that is the profit-maximizing level of output.

In the long run, if firms under perfectly competitive markets start earning higher profits, more entrepreneurs will be attracted to such business ventures. As a result, production will increase. This translates to an increase in the aggregate supply. Consequently, the supply curve will shift outwards the right. When the supply curve shifts to the right, the equilibrium price will fall to the same demand curve.

In the long run, all firms will operate at a point where marginal cost (MC) intersects at the lowest level on the average total cost (ATC) curve.

This means that new firms entering the market won’t post profits at this point from an economic profit standpoint because total revenue equals total cost. In the long run, perfectly competitive markets operate at practically zero economic profit. Also, note that the demand curve at this point is perfectly elastic. This elasticity is represented by a horizontal line.

As firms under this market structure start reporting higher profits, more firms will venture into the market. Since entrant prices are low, customers will shift to buying products from these new firms. This will reduce the demand for firms that produce similar goods.

With the entry of new firms, the demand curve experienced by each firm is shifted so that price is equal to the average total cost (P=ATC), resulting in zero economic profit.

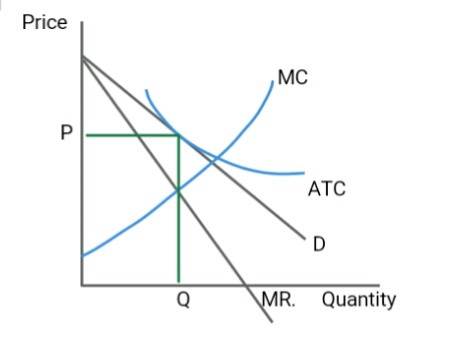

MR=MC in monopolistic competitive markets implies the firm will continue to produce the same quantity, but it will no longer earn positive economic profits.

As a result, the economic profits realized by monopolistically competitive firms will fall. Further, firms will incur advertising costs for product differentiation.

There is a possibility for economic profits in oligopoly markets in the long run. However, the market share of a dominant firm will decline in the long run. As is always the case, profits will attract more firms to enter the oligopoly market.

Marginal costs incurred by entrant firms fall. Likewise, the profitability of the dominant firm declines. The reactions of entrant firms are included in the optimal pricing strategy.

Some firms may decide to incorporate innovation to maintain market leadership. For example, Shell’s gasoline helps clean the engine valves and fuel injectors. However, these innovations are usually not very effective at maintaining the market share of the dominant firm.

Monopolies can make economic profits even in the long-run. This is because the long-run equilibrium creates room for every input to change. A monopoly must be protected by entry barriers.

For monopolies that are regulated, there exist a number of solutions to long-run equilibrium. Below are a few examples of the solutions.

Question

A monopoly most likely profits when:

A. price equals marginal cost (P=MC).

B. marginal revenue equals average total cost (MR = ATC).

C. marginal revenue equals marginal cost (MR = MC).

Solution

The correct answer is C.

To arrive at the monopolist’s profit maximizing level of output, its marginal revenue is equated to its marginal cost. This, indeed, is the same profit-maximizing condition that a perfectly competitive firm uses to determine its equilibrium level of output.

In fact, the condition that marginal revenue equals marginal cost is used to determine the profit-maximizing level of output of every firm. This is the case regardless of the market structure in which a firm operates. However, the monopolist charges a price that is higher than where the marginal revenue curve and marginal cost curve intersect, creating room for economic profit.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.