The Black-Scholes-Merton Model

After completing this reading you should be able to: Explain the lognormal property... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

A futures contract is a standardized, exchange-tradable obligation to buy or sell a certain amount of an underlying good at a specified price on a specified date.

Long exposure in a futures contract means the holder of the position is obliged to buy the underlying instrument at the contract price at expiry. The holder will make a profit if the price of the instrument goes up. Conversely, they will make a loss if the price goes down. The long futures position can be entered by a speculator who expects the price to rise.

Short exposure in a futures contract means the holder of the position is obliged to sell the underlying instrument at the contract price at expiry. The holder will make a profit if the price of the instrument goes down. Conversely, they will make a loss if the price of the underlying rises dramatically.

Open interest refers to the number of existing contracts at any point in time. Consistently, the number of long positions always equals the number of short positions. As such, open interest can be described as the number of net long contracts (short contracts).

The net interest of trade is zero at the beginning of the contract. The open interest slowly rises as the trade progresses to a maximum amount seen before delivering the contract. For instance, consider a futures contract between two parties:

Exchanges should clearly be defined as what is being traded in a futures contract. In a case where there are diverse deliverables, the location and time of delivery should be clearly defined, and the party with the short position has the right to choose. The specifications of the futures contract include:

Exchanges should determine the size of their contracts to cater to both small (retail) and large (large corporations) scale traders. Compared to an agricultural product, the value of what is delivered for a contract on a financial asset is typically much higher.

Futures contracts on commodities require the specification of the delivery location while taking into consideration the transportation costs. Note that for some contracts, transportation cost also determines the price of the futures contracts.

The time to delivery is usually specified in months. At the close of trading, the price of the futures contract is known as the settlement price. It determines the amount and the trader who gets the variation margin.

The future price can either start above or below the spot price. It, however, converges at the spot price as the period of delivery nears. If the prices do not converge and the futures price is above the spot price, traders can hedge by:

If the price is below the spot price, traders will buy the asset and make the future prices rise towards the spot price. Arbitrage opportunities such as these do not last long in the market since the investors take advantage and disappear quickly.

Typically, futures contracts are written on financial assets such as currencies and commodities such as agricultural products. For financial assets, the definition of underlying is plain and simple. For instance, the CME Group defines the underlying asset of one contract on euros as 125,000 euros.

In the case of commodities, grading (based on quality) must be clearly specified of the commodities to be delivered. For instance, a contract should specify if the actual orange fruits or their concentrates are delivered.

Failing to specify the grading system of commodities by the exchange could cause the contract to be terminated. The trader in a short position can deliver low-quality products, which the trader in a long position can reject.

Price limits are set by the exchange and subject to change from time to time. Price limits within which future prices can move in either direction. These movements are known as limit movements. If the limit movements are exceeded, trading is stopped.

When a limit is reached and results in a price increase, the contract is termed the limit up. Conversely, if the limit movement results in a price decrease, the contract is called limit down.

The price limits help in preventing huge price movement due to speculation. On the downside, if the price limits result from the new information reaching the market, then the price limits obstruct the determination of the true market prices.

Position limit cabs the size of a position that a speculator can hold in the futures contract. Position limits are meant to prevent speculators’ domination, which can result in an unacceptable market influence. Position limits are in tens of thousands of contracts.

Delivery of the underlying assets rarely happens in the futures markets as traders strive to close out their positions before the contract’s maturity.

Assets can, however, be traded at spot markets using the most recent settlement price. Thus, the mechanics of delivery is crucial in futures markets.

The delivery time of a contract varies from one contract to another. The delivery process of the contract is initiated when a trader in a short position issues a notice of intention to deliver to the exchange central counterparty clearing house (CCP). The notice includes the number of contracts to be delivered and, in the case of commodity products, the grade of the commodity and location of delivery.

The exchange then chooses one or more traders with a long position to accept the contracts. Typically, traders who have had net long positions are allocated the delivery notices, but sometimes traders are allocated randomly. The members cannot deny the delivery notices and are often given a short period of time to transfer the contracts to other members.

The first notice day is the first day when the delivery notice is sent to exchange CCP. The last notice day is the last day when submission of the delivery notice to exchange CCP can be done.

The price paid for an asset is defined as the most recent settlement price and sometimes adjusted for the delivery location, grade, warehousing cost, and other factors.

Cash settlements save traders’ delivery processes and costs. However, regulators try to discourage cash settlements since they resemble a gambling process. Therefore, delivery of physical settlements is preferred when it is possible.

However, CME Group’s futures contracts on the S&P 500 are settled in cash. Other contracts settled in cash are contracts that depend on weather and real estate prices.

The futures market participants include:

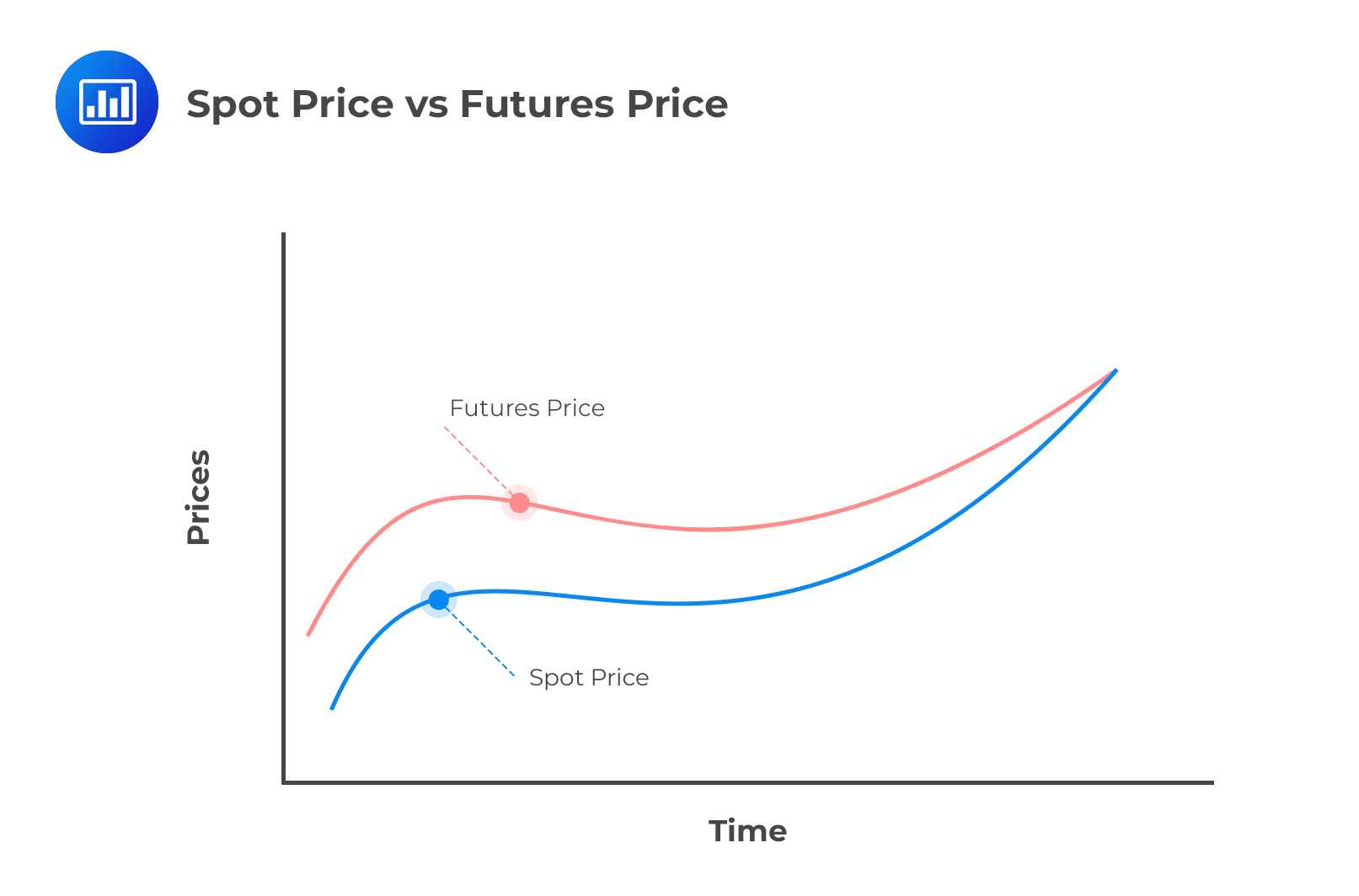

The spot price is the current market price at which an instrument or commodity is bought or sold for immediate payment and delivery. On the other hand, the futures price is the price of an instrument/commodity today for delivery at some point in the future, called the maturity date. The difference between the two is called the basis.

$$ \text{Basis}=\text{Spot Price – Futures Price} $$

As the maturity date nears, the basis converges toward zero, i.e., the spot price tends towards the futures price. The two rates must be equal as long as no arbitrage opportunities exist on the actual maturity date. At maturity, the futures price becomes the current market price, which is actually the definition of the spot price.

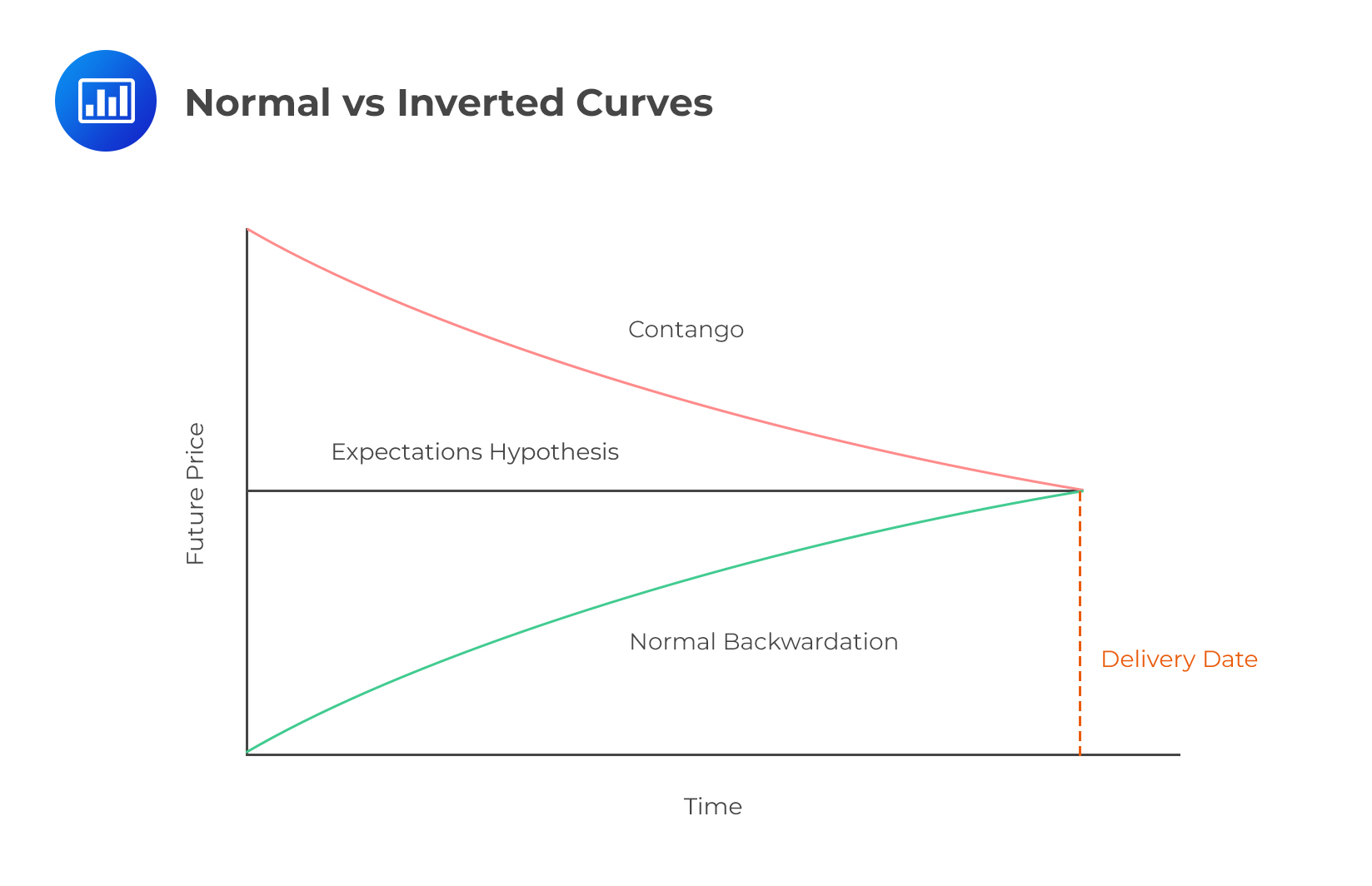

Normal and Inverted Futures Markets

Normal and Inverted Futures MarketsA normal futures market, also known as a Contango market, means that futures contracts are trading at a premium to the spot price. For example, suppose the price of a barrel of crude oil today is $50 per barrel, but the price for delivery in three months is $53: the market would be in Contango. On the other hand, if crude oil is trading at $50 per barrel for delivery right now, and the three-month contract is trading at $45 per barrel, then that market would be said to be inverted (backwardation).

A normal futures curve will show a rising slope as the prices of futures contracts rise over time. An inverted futures curve will show a falling slope as the prices of futures contracts fall over time.

Terminating a Futures Contract

Terminating a Futures ContractTraders with short or long positions in futures contracts can terminate them in one of four ways:

A trader uses a futures order or options order to tell his broker exactly what to buy or sell when to do it, and at what price. There are several order types:

Orders are to be executed by the end of the day, failure to which leads to cancellation. Traders specify other periods of time when the trade is active. A fill-or-kill order is an order that is canceled if not executed within a few seconds. An open order or good-till-canceled order is an order that is only canceled upon a trader’s request; otherwise, the order remains open for the remaining life of the futures contract.

Regulations vary from country to country. The work of these regulators include:

Gains and losses from futures markets are accounted for as they occur, a valuation process called marking to market. Consider the following example:

Consider an oil company with the fiscal year ending December. The company sells 1000 two-year futures contracts at the end of May when the futures price is $65 per barrel of crude oil. Each contract consists of selling 1,000 barrels of crude oil. Over the period of two years, the following happened:

The profit to the oil company is calculated as follows:

First year: (65-62.5)× 1,000 × 1,000 = $250,000

Second year: (62.5-61)× 1,000 × 1,000 = $150,000

Third year: (61-64.5)× 1,000 × 1,000 = -$350,000

Typically, futures are settled daily so that the cash in line with profits earned in the years is accounted for.

Accounting for the profits and losses when hedging using futures contracts can lead to high earning volatility, which goes against the notion of hedging. Thus, if a company hedges against its position, it must take into consideration the hedging accounting.

The hedging accounting allows the profits (or losses) from the hedging strategy to be recognized simultaneously as the loss (or profits) on the hedged items.

Examples of regulations are: the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) has provided statements FAS 133 and ASC 815, which explains when hedge accounting can and cannot be used by US companies. On the same note, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has given out IAS 39 and IFRS 9.

If we consider the oil company example above and assume that it qualifies for hedge accounting, the gain of $500,000 [=(65-64.5)× 1,000 × 1,000 ] will be accounted for in the third year.

The rules governing hedging accounting are strict in that the hedge must be entirely documented (for example, with regard to items being hedged and hedging instruments). Moreover, the hedge must be classified as effective, implying that and economic activity that is not affected by credit risk must link the hedging instrument and the hedged instrument. Moreover, the efficacy of the hedge must be tested regularly.

They both are an agreement to trade an item at a later date at a pre-determined price.

$$ \begin{array}{l|l} \textbf{Futures} & \textbf{Forwards} \\ \hline \text{Traded on an exchange.} & \begin{array}{l} \text{Traded in an OTC market and} \\ \text{are thus more prone to credit} \\ \text{risk.} \end{array} \\ \hline \begin{array}{l} \text{Both financial and non-financial} \\ \text{variables can be traded.} \end{array} & \begin{array}{l} \text{Mainly traded on interest rates} \\ \text{and foreign exchange.} \end{array} \\ \hline \begin{array}{l} \text{Trades are settled on a daily} \\ \text{basis.} \end{array} & \begin{array}{l} \text{Trades are settled at the end of} \\ \text{the life of the asset.} \end{array} \\ \hline \begin{array}{l} \text{Delivery is rare as traders close} \\ \text{out positions before the} \\ \text{delivery date.} \end{array} & \text{Actual delivery is made.} \\ \hline \text{The delivery date is specified.} & \begin{array}{l} \text{The delivery period is specified} \\ \text{and can be a whole month.} \end{array} \\ \end{array} $$

Question

A trader wishes to sell different grades of corn. Which of the below statements best describes how the price of the corn should be quoted?

A. Quote prices would be the same price for all corn

B. Quote prices would be different prices for each harvest period

C. The exchange would randomly decide which grade would be a higher/lower price

D. Quote prices would correspond to the quality of the corn

The correct answer is D.

Different prices should be quoted for each of the grades available. The prices should further correspond to the quality of the corn. The highest grade should be priced more than the lowest grade.

A is incorrect: The same price should not be quoted for all corn. This is because the price will not be a true reflection of the value of the corn.

B is not the BEST answer: The prices should not only be different but also reflect the grade of the corn.

C is incorrect: Randomly deciding on the price of the corn may lead to overpricing low-quality corn and underpricing high-quality corn.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.