Governance

After completing this reading, you should be able to: Define risk management responsibilities... Read More

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

Credit risk is defined as the probability of a financial loss resulting from a counterparty’s failure to fulfill its financial obligations. This risk is inherent in any transaction where there’s a possibility that the other party, known as an obligor, may be unable or unwilling to make payments as promised or on time. Credit risk arises from various contractual obligations, which may not always be formalized in writing; verbal contracts can also be legally binding in many jurisdictions.

The following are examples illustrating how credit risk emerges:

Credit risk management necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the terms and conditions associated with financial distress. Insolvency, default, and bankruptcy are three pivotal concepts that represent various stages or facets of financial difficulty.

Insolvency marks the initial phase of financial distress. It is a condition where an obligor’s liabilities surpass its assets, rendering them incapable of meeting their financial obligations. It’s crucial to note that while insolvency often precedes bankruptcy, the two terms are not interchangeable. Insolvency refers to a financial state, a precursor that may or may not lead to the legal proceedings of bankruptcy. This condition can be triggered by various factors, including poor cash flow management, rapid business expansion without adequate returns, or a significant drop in market demand for products or services.

Default occurs when an obligor fails to fulfill their contractual commitments. This could be a result of not making a scheduled payment, breaching a covenant, or violating other terms set within a financial agreement. Default is often associated with insolvency, where the entity does not possess sufficient resources to honor its debts. However, it’s important to acknowledge that default can also arise from illiquidity issues, where the obligor holds assets but cannot liquidate them swiftly enough to meet immediate financial demands. This distinction underscores the complexity of default, where factors beyond mere asset deficiency come into play.

Bankruptcy represents the legal culmination of financial distress. It ensues when an obligor, unable to fulfill its obligations, seeks legal protection under specific bankruptcy laws, such as Chapter 11 or Chapter 7 in the United States. This process involves a court reviewing the financial situation of the defaulting entity and initiating negotiations among stakeholders, including management, creditors, and sometimes shareholders. The primary aim is to devise a viable recovery plan, which may involve asset liquidation or restructuring of financial arrangements. The court’s intervention is a critical juncture, seeking to balance the interests of all parties involved and, wherever possible, to salvage the business by reorganizing its debts and operations.

Understanding the evolution and variety of transactions that generate credit risk is pivotal for modern credit risk management. Historically, the identification of credit risk was relatively straightforward, involving direct exchanges of cash or products. However, the landscape of credit risk has significantly diversified, especially with the advent of modern banking products.

Let’s now look at some of the most common transactions that generate credit risk, in greater detail:

Loan commitments and financial guarantees entail a promise to lend funds in the future, contingent upon certain conditions. The primary risk arises if the borrower’s financial situation deteriorates, increasing the likelihood of default. For instance, a bank may extend a line of credit to a company based on its current financial health. If the company’s operations subsequently suffer, impacting its revenue and cash flow, the bank faces increased credit risk should the company draw on the line of credit.

Leasing involves an entity (the lessor) making an asset available to another (the lessee), who commits to regular future payments. The lessor often finances the leased asset and relies on the lessee’s payments to service this debt. The credit risk materializes if the lessee fails to make timely payments, potentially due to business downturns or inefficient management, impacting the lessor’s ability to meet its financial obligations.

This type of transaction occurs when a seller provides goods or services without immediate payment, sending an invoice to be paid within a set period. The risk lies in the buyer failing to fulfill the payment, affecting the seller’s cash flow and financial planning. An example could be a manufacturing company shipping goods to a retailer with a 30-day payment term, during which the retailer experiences a significant drop in sales and struggles to pay the invoice.

Depositors face credit risk when they place their money in a bank. If the bank encounters financial difficulties and becomes unable to return the deposited funds, depositors bear the loss. The credit risk is particularly pronounced during financial crises, where even large and seemingly stable financial institutions may become insolvent.

Policyholders face credit risk if the insurer becomes unable to meet its claim obligations. This can happen if the insurer has underpriced its policies or has not managed its investment portfolio effectively, leading to insufficient reserves to cover the claims. A real-world example is the failure of insurance companies during natural disasters when the volume and value of claims can far exceed the insurer’s expectations and reserves.

These transactions involve the exchange of cash or securities with a commitment for a future reversal. Credit risk arises if one party fails to comply with the terms, for instance, by not returning the securities, or not paying the agreed amount of cash at the end of the agreement. The risk is amplified if the value of the securities fluctuates significantly during the term of the agreement.

Derivatives such as interest rate swaps, foreign exchange futures, or credit default swaps, involve commitments based on future market conditions. The credit risk lies in one party failing to honor their financial obligation, which can be influenced by changes in market rates, currency exchange rates, or the creditworthiness of referenced entities. A notorious example is the 2008 financial crisis, where the collapse of the housing market led to massive losses for holders of mortgage-backed securities and related derivatives.

In each of these transactions, the common element is the uncertainty regarding the counterparty’s ability to fulfill its obligations, underlining the multifaceted nature of credit risk. Effective credit risk management, therefore, requires a deep understanding of the specific risks associated with each type of transaction, combined with rigorous assessment and monitoring practices.

Credit risk exposure affects all institutions and individuals, either by choice or circumstance. Banks and hedge funds actively engage in and profit from managing credit risk, while individuals may invest in fixed income bond funds for higher returns compared to U.S. Treasury bonds. For industrial corporations and service companies, credit risk is an inevitable result of selling goods or services without upfront payments, making it a by-product of their core operations.

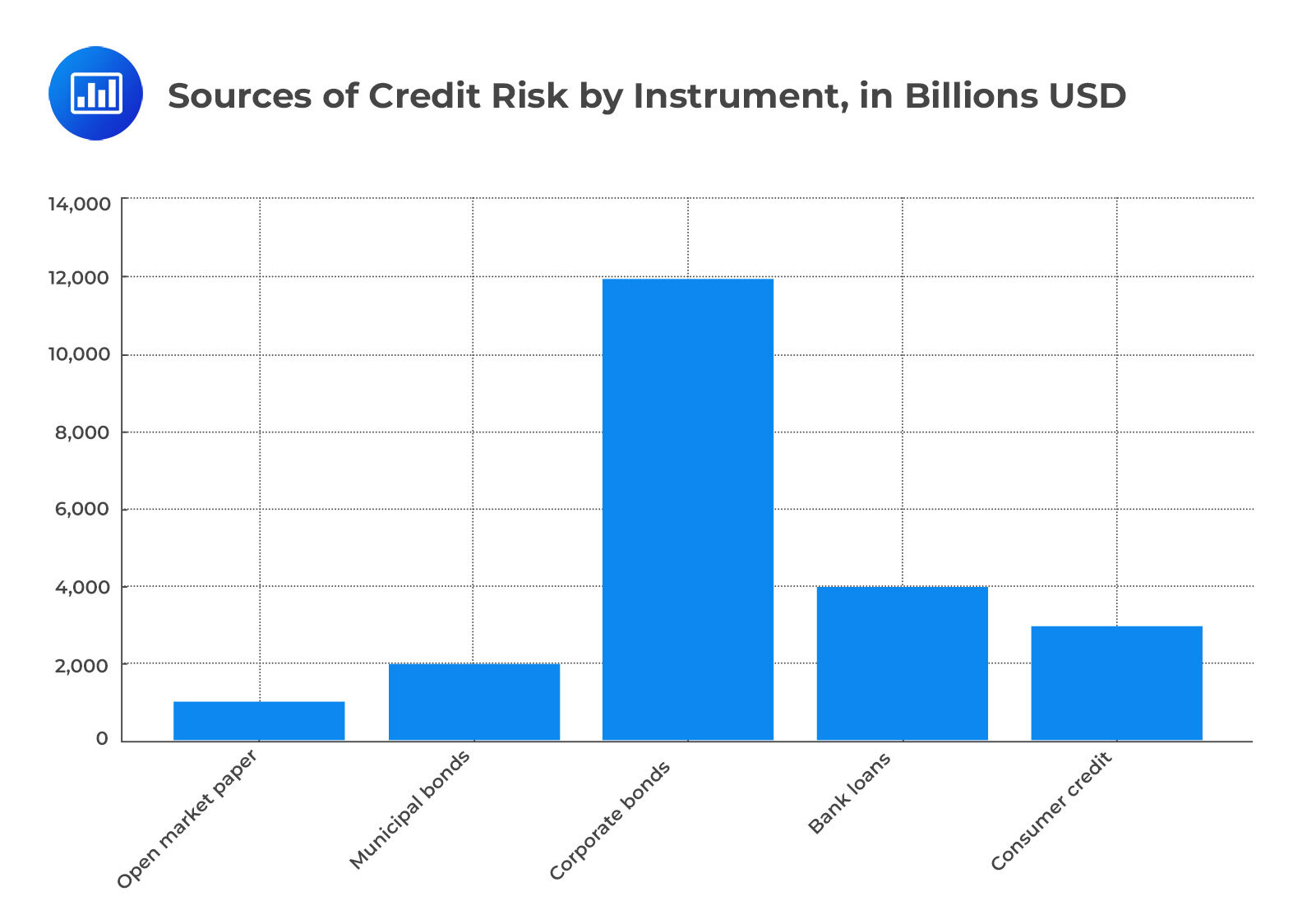

The credit risk exposure in U.S. borrowing instruments as of September 30, 2020, was primarily dominated by corporate obligations, despite the presence of roughly $55.5 trillion in debt outstanding in the markets. This figure encompasses instruments typically not associated with credit risk, such as U.S. Treasury obligations and government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) securities. When considering credit risk, the majority is rooted in the corporate sector, specifically in corporate bonds, bank loans, and commercial paper. These instruments reflect the extensive role of corporations in the credit market, underscoring the significance of understanding these elements for comprehensive credit risk assessment.

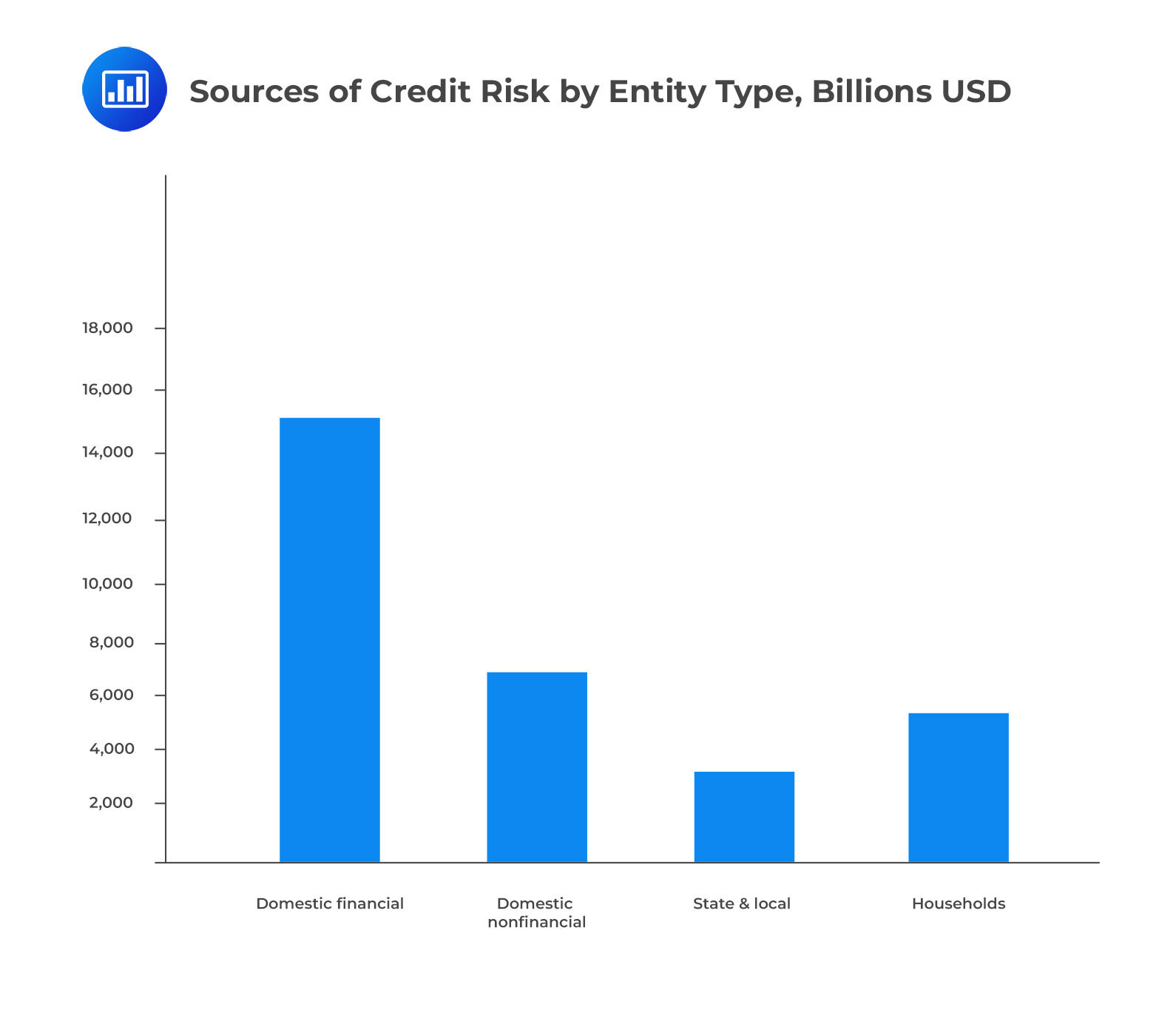

The next graph shows the sources of credit risk exposure by entity type, highlighting that financial corporations contribute substantially more to credit risk than nonfinancial corporations and households combined. This demarcation is significant, especially considering that forms of borrowing like federal government debt and majority of household-mortgage debt (mainly agency-backed) are not included in this categorization, owing to their perceived low or negligible credit risk exposure. This distinction accentuates the pivotal role of financial corporations in the credit market landscape and underlines the need for nuanced understanding and management of credit risk within this sector.

Banks

BanksBanks are primary players in the credit risk landscape due to their central role in providing loans and other credit facilities. They are exposed to credit risk through various activities, such as direct lending, issuing letters of credit, and even through off-balance-sheet activities like loan commitments and financial guarantees.

The traditional banking model relies heavily on understanding and managing this type of risk. Banks earn their income predominantly through the interest they charge on loans, which compensates them for the credit risk they assume. If a borrower defaults, it can lead to a direct financial loss for the bank. Therefore, they employ rigorous credit assessment procedures when deciding to grant credit and continuously monitor the creditworthiness of their borrowers.

Moreover, banks are required to hold a certain level of capital reserves as part of regulatory requirements like the Basel Accords, which provide a buffer in case of loan defaults. Advanced risk management teams within banks use various measures, including credit scoring models and risk ratings, to manage their portfolio exposure. The health of a banking institution is often tightly linked to its ability to manage credit risk effectively.

Asset managers handle the mobilization and investment of funds on behalf of individuals and institutions, aiming to fulfill specific investment goals and risk-return preferences. For instance, conservative investors may choose money-market funds that have minimal credit risk exposure, while other investors might be inclined toward mutual funds specializing in equities or high-yield debt instruments.

Due to the sheer volume of assets under management, firms like Blackrock and Vanguard Group are exposed to significant credit risk on behalf of their clients. The investment choices made by asset managers must carefully consider the creditworthiness of corporate and sovereign entities to protect the performance of the funds they manage. Asset managers’ ability to gauge and manage credit risk is integral to maintaining investor confidence and ensuring the sustainability of their investment strategies.

Hedge funds, with their large investment pools, face substantial credit exposure daily. Their investors typically have a higher risk appetite, looking for aggressive returns, and therefore, hedge funds are known to invest in a range of riskier financial instruments, often beyond the traditional asset manager’s reach.

They contribute to the liquidity of the financial markets by partaking in a variety of transactions that enable the transfer of risk. For example, hedge funds might engage in buying distressed loans or selling credit protection, activities that require sophisticated risk management measures. Given their role in financial markets, hedge funds must maintain a robust credit risk management practice to safeguard investor capital against potential losses.

For an insurance company, managing credit risk is about balancing the expected return, which might favor shareholders, and maintaining a low-risk profile to reassure policyholders. They have to manage portfolios comprising a mix of safe, low-yield investments, like Treasury bonds, and riskier, higher-yielding assets.

Insurance companies use dedicated teams to handle their credit risk management, assessing and monitoring the credit positions they hold, even when these assets are managed by third-party asset managers. For life insurance companies, in particular, they also manage policyholder money in separate accounts, which requires a fiduciary duty of care similar to that of asset managers.

Corporations outside the financial sector also face credit risk, mainly through their receivables — the money owed by customers who buy goods or services on credit. Companies must continually assess the creditworthiness of their clients and manage the risk that customers might not pay their invoices.

Additionally, corporates may hold deposits across multiple banks to reduce their exposure to any one institution’s failure. And for some industries, engaging in derivative trading, such as commodity futures, introduces an additional layer of credit risk. This necessitates a strategic approach to credit risk management to safeguard the firm’s financial health.

Credit risk also impacts individuals, especially those who invest in various financial instruments seeking higher returns than those offered by risk-free government bonds. Those investing in corporate bonds, for example, bear the credit risk that the issuing company may face financial difficulties and possibly default on their obligations.

Individual investors must be keenly aware of the credit quality of the instruments they invest in and depend on credit rating agencies, market analyses, and perhaps their own due diligence to manage the credit risk inherent in their investment portfolios. The management of credit risk for individual investors is often about balancing the pursuit of higher returns against the potential for financial loss.

Acknowledging the wide range of transactions that generate credit risk is critical for risk management practices. Awareness of these transactions is necessary as financial landscapes evolve, leading to the development of new products and services that carry inherent credit risks. This expansive view ensures that institutions are better equipped to identify, measure, and manage the risks arising from their business activities.

An essential characteristic of credit risk is that it is controllable; it is not a random force that impacts a company without warning. Credit risk can often be anticipated when its fundamental sources are well understood. Therefore, actively managing credit risk is of paramount importance, and to ignore such management would be unjustifiable. This implies that there must be proactive engagement in understanding, measuring, and mitigating credit risk.

Profitability hinges on the basic principle that the less money lost due to defaults, the more profit retained. Especially for businesses with low-profit margins, effective credit risk management can significantly influence the bottom line. Minimizing losses associated with credit risk directly contributes to overall profitability and financial health.

Properly managing credit risk is also vital for maintaining an adequate return on equity. Companies cannot operate profitably if they hold excessive equity capital, which can dilute returns. On the other hand, relying too heavily on debt capital is not a viable approach either; debt carries its own risks and does not serve to absorb losses.

The long-term sustainability of a company depends on managing credit risk effectively. Prudent risk management helps avoid large, unexpected losses that can be catastrophic, leading to bankruptcy even for non-financial corporations. During times of financial crisis, such as in 2007, certain organizations that wielded strong credit risk management principles fared far better than their peers, underscoring the value of a disciplined approach to credit risk.

Individuals also manage credit risk in their investment activities, such as when choosing between investment vehicles like high-yield versus investment-grade bond funds. The decision to invest in instruments with higher credit risk inherently seeks to achieve a larger return by accepting a greater risk of loss.

The motivations for managing credit risk go beyond the avoidance of negative events to the active cultivation of a stable and profitable enterprise. Both financial and non-financial firms—as well as individual investors—have significant reasons to prioritize robust credit risk management. This is the cornerstone of sustaining profitability, optimizing capital utilization, ensuring longevity, and achieving return objectives. This responsibility extends across the spectrum of financial activities, where credit risk is a factor, underscoring the need for ongoing vigilance and strategic risk management initiatives.

Practice Question

Hedge funds participate in various high-risk investment activities and are known for their aggressive investment strategies that include short-selling and dealing in distressed loans. Understanding how hedge funds operate and manage credit risk can provide crucial insights into the systemic risks present in the financial sector. In the context of credit risk, how do hedge fund strategies differ fundamentally from traditional financial institutions?

- Hedge funds primarily invest in low-risk government securities to ensure principal protection.

- Hedge funds seek out opportunities to profit from entities facing financial distress through short-selling or other means.

- Hedge funds have less exposure to credit risk because they invest their capital in high-quality assets only.

- Hedge funds mitigate their credit risk entirely by using derivative counterparty exposure as a hedge.

Correct Answer: B)

Some hedge funds employ strategies that find opportunities in the potential default of entities, in contrast to traditional financial institutions that focus on avoiding defaults to protect shareholder value. Hedge funds use instruments like credit default swaps and engage in short-selling to potentially profit from such scenarios.

A is incorrect: Investing in low-risk government securities is not the primary strategy described for hedge funds in the context of credit risk.

C is incorrect: Hedge funds do not limit themselves to high-quality assets; in fact, they often take on riskier positions not typically accessed by traditional asset management firms.

D is incorrect. While using derivatives can be part of a hedge fund’s strategy, hedge funds do not completely eliminate their credit risk exposure through this method alone.

Get Ahead on Your Study Prep This Cyber Monday! Save 35% on all CFA® and FRM® Unlimited Packages. Use code CYBERMONDAY at checkout. Offer ends Dec 1st.